Regarding Fathers

There isn’t anyone out there who doesn’t expect Clint Eastwood’s Flags of Our Fathers (DreamWorks/Paramount) to rank as a probable Best Picture contender later this year, but it won’t be screened for another four or five months or so why not chill and write about something else?

Then I figured, “Naaah.” I knew I could at least get an idea of how this World War II tone poem will play if I would just focus and sit down and read a March 2005 draft of Paul Haggis’s script that’s been sitting on my desktop for the last month or two. So I did that last night, and I have to say, in all candor…

Clint Eastwood during the shooting of Flags of Our Fathers last year on a black-sand beach in Iceland, which subbed for Iwo Jima.

I’m not saying it’s not a likely Oscar favorite, or that it doesn’t have the earmarks, in fact, of a presumptive front-runner. But all I can really say for sure, having slept on Haggis’s 119-page script, is that I’m genuinely impressed, but at the same time I’m wondering how much broad-based appeal the film will turn out to have.

Put bluntly, the script reads like Saving Private Ryan‘s artier, more glum-faced brother. It has a lot of the same battle carnage and then some, a bit of the old- WWII-veteran-looking-back vibe and minus the manipulative Spielberg tearjerk factor but also with less of a narrative through-line.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

Fathers is a sad, compassionate, sometimes horrifically violent piece that’s essentially plotless and impressionistic and assembled like a kind of time-tripping poem — a script made from slices of memory and pieces of bodies and heartfelt hugs and salutes from family members and politicians back home, and delivered with a lot of back-and-forth cutting.

So it’s basically a montage thing that’s obviously more of an art film than a campfire tale, and that means that the sector that says “give us a good story and enough with the arty pretensions” is going to be thinking “hmmmm” as they leave the screening room.

Unless, of course, there’s more to Eastwood’s film than can be gleamed from Haggis’s script, in which case fine and I can’t wait.

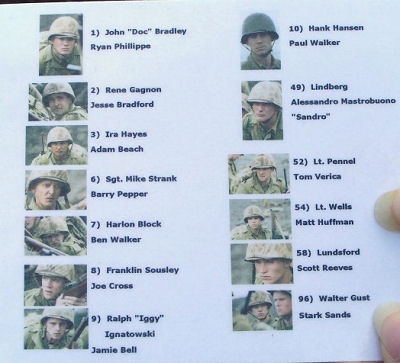

The characters and the cast

Flags of Our Fathers is about the loneliness and apartness of young soldiers living in two worlds — the godawful battle-of-Iwo-Jima world where everything is ferocious and pure and absolute, and the confusing, lost-in-the-shuffle world of back home, where almost everything feels off and incomplete.

There are many, many characters in Flags but it’s basically about three of the six young Marines who raised the American flag on a pole atop Mt. Surabachi during the Iwo Jima fighting in early 1945, resulting in a photo that was sent around the world and came to symbolize the valor of U.S. soldiers.

Three of the flag-raisers died in battle soon after, but the three survivors — John Bradley (Ryan Phillipe), Ira Hayes (Adam Beach) and Rene Gagnon (Jesse Bradford) — were sent home to take bows and raise funds and build morale on a big public relations tour arranged by the military.

And the film — the script, I mean — is primarily about their vague feelings of alienation from their admirers and even, to some extent, their families. And vice versa.

(l. to r.) Ryan Phillipe, Adam Beach, Jesse Bradford

Heroes, a narrator says at the end, are something we need and create for ourselves. But the soldiers don’t get it or want it. They only feel for each other. They may have fought for their country, but they died for their friends.

Fathers will be what it will be, and if it’s not a big Oscar thing at the end of the day, it’ll certainly settle in with a lot of us as a mature, respectable meditation piece with its head and heart in the right place, and Eastwood and Haggis with another big feather in their caps.

And maybe Adam Beach, who has the meatiest role, with a Best Supporting Actor nomination…who knows? Ira Hayes, portrayed by Tony Curtis in a 1961 Delbert Mann film called The Outsider, is an emotionally unruly Native American who is far less able to deal with the guilt of being called a war hero than the other two, and it eventually takes him down.

As ridiculously early as this may sound to the tut-tutters out there, the early front-runner status for Fathers comes from four headwind factors:

(1) It’s been directed by Eastwood, a two-time Best Picture Oscar winner (Million Dollar Baby , Unforgiven) who’s made plenty of genre-type films but when he’s in his pared down poetic mode, look out. Especially now that’s reached a kind of Bunuelian master stage in his career.

(2) The writing hand of Haggis, arguably the hottest and most Oscar-awarded screenwriter around these days, having just won the Original Screenplay Oscar for Crash after his Million Dollar Baby screenplay was Oscar-nominated in the Best Adapted category the year before.

(3) The whoa-he’s-directing-two-movies-about-the-same-subject factor, which is about Eastwood shooting a second Iwo Jima film, called Red Sun, Black Sand, that takes the perspective of Japanese soldiers during the conflict, and particularly that of a Japanese general to be played by Ken Watanabe. This is roughly the DGA equivalent of a top-drawer actor gaining 40 pounds or playing a handicapped person in an Oscar-bait performance. The sheer effort — the audacity — of making two Iwo Jima movies and releasing them both this year (within three or four months of each other) means attention will certainly be paid.

(4) The “I love you, Dad” or “I miss you, Dad” emotional factor among all the 40ish and 50ish baby-boomer Academy members whose fathers either served in World War II or were part of that generation, and have either passed or are not far from this. The Academy declined to give the Best Picture Oscar to a half-great World War II film when they blew off Saving Private Ryan. Even if it’s not unanimously adored, Flags of Our Fathers will probably be the last ambitious and high-pedigree film to be made about that conflict, and support will come from that. World WWII stories are fading out along with the men who fought it, so Flags is most likely going to be the last big hurrah.

And all in all, Fathers is a hell of a three-course meal and a very ambitious film (especially coupled with the currently rolling Japanese variant) for a 75 year-old director to grapple with. I love Eastwoood’s energy and ambition, but let’s see what happens as far as industry acclaim and awards and all that.

Spike’s Slam-Dunk

I haven’t seen the tracking on Inside Man (Universal, 3.24), but I’ll tell you one thing for damn sure. It’s going to be the top box-office dog when it opens five days from now. In fact, it’s quite obviously…hello?…the most commercial film ever directed by Spike Lee.

It’s going to to put arses in seats because it’s pretty much devoid of any African- American social concerns. And because it’s a deft, smooth and unpretentious big-studio thriller that’s always a step or two ahead of the audience (including those who pride themselves on being able to figure out plot twists). And because it’s a cleverly configured, Dog Day Afternoon-ish bank-robbery film with an edge.

Invoking Dog Day Afternoon might be the wrong way to put it. Inside doesn’t have the borough personality of that Sidney Lumet film, and its thieves aren’t oddball screw-ups.

Four super-organized hardcore pros (led by Clive Owen) hit a downtown Manhattan bank with military precision, and their first maneuver is to take hostages. The fuzz (led by detectives Denzel Washington and Chiwetel Ejiofor, and backed up by a uniformed Willem Dafoe) soon get wind and surround the building, and the usual tense negotiations and psychological stand-offs ensue.

Seen it before? Same-old same-old with the deck reshuffled? Okay, maybe, to some extent…but Inside Man has the panache and blue-chip confidence of a slam-dunk enterprise, and is one of those nicely refined thrillers that keep you guessing and fully engrossed. Not especially violent or sensationalistic…just a good, gripping pulse-pounder.

Add to this the contributions of costars Jodie Foster (as a high-end fixer and financial consultant) and Christopher Plummer (as a loaded philanthropost and friends-of-powerful-people type) and…well, they definitely sweeten the pot.

It’s surprising at first to find the director of Do The Right Thing doing a genre thriller, although it’s clear early on he knows precisely what he’s doing.

Chiwetel Ejiofor, Denzel Washington in Inside Man

The action is centered on an old Wall Street-area bank — Manhattan Trust — owned by Plummer’s character. The action kicks in right at the start when Owen and his three conspirators kill the surveillance cameras and take over the bank and force everyone to put on identical jump-suits…

I don’t know if it’s such a good idea to run down the particulars.

The main thing is that Owen’s guy, Dalton Russell, is very steady and on top of things, and in no way some kind of hair-trigger asshole. The curious thing is that he doesn’t seem very interested in bagging the heaps of cash in the vault (like the guys in Heat were)…and the film doesn’t give any decent hints what he’s after for a good long while.

Washington’s detective, an old-fashioned guy with a thin moustache, a shaved head and a straw hat, doesn’t do all that much, preferring to watch and wait rather than attack and risk lives. He’s cool and not of a mind to upset anyone or anything. He tries a couple of times to trip up or fake-out Owen, but nothing radical….just fun stuff.

Then we start seeing portions of after-the-fact hostage interviews, shot with a grainier, half-sepia color scheme. This deflates the suspense a bit because it tells us early on the robbers were never identified, probably…although we’re not entirely sure. It’s still interesting, though. Everything in this film is. Nothing boring or numbing or flaccid.

I’m not going to spill any more. The only thing I feel compelled to mention are the strange sartorial choices made by Denzel’s detective. He dresses like it’s 1964 and Malcolm X is still alive and he’s the owner of an illegal Newark, New Jersey, bookmaking operation. Or a jazz club owner in Tennessee in 1958. Very strange. The idea seems to have been to make Denzel’s detective look like some kind of anachronism.

Washington is unexceptional but fine. Owen is icy, commanding and a very cool bad guy..even though he wears a mask for a good portion of the film. Ejiofor is sturdy, Dafoe is fine, Foster is cool and so is Plummer. Nobody is rewriting the book on great acting here, but they’re all pros and it all goes down like low-fat chocolate yogurt.

For a film that last 128 minutes, Inside Man whips right by. It seems to be over and done within 95 or 100 minutes, tops.

This is a first-rate shallow entertainment, and I can’t wait to see it again. It’s not a movie for munching popcorn through, or making lobby cell-phone calls or taking bathroom breaks while it’s playing. It’s a great film for saying “please be quiet” to the people sitting behind you because they’re won’t shut the fuck up and you really need to hear every line. It’s one of those “please, Michael Moses…can I come to the premiere party?” movies.

Enemies Watch

Last Friday night I read James Vanderbilt’s gripping, pared-to-the-bone screenplay of Against All Enemies, an adaptation of former terrorism czar Richard Clarke’s bombshell novel about the failures of the Clinton and Bush administrations to stop the terrorist plotters who eventually brought about the 9.11 attacks.

The script, yet another example of a fascinating run of political films being made by mainstream Hollywood these days, is the basis of an upcoming Columbia feature that Crash director Paul Haggis “[hopes] to shoot…this year,” according to what he told N.Y. Times reporter Sharon Waxman in a piece that ran last Tuesday.

My first casting question, apart from the matter of whether or not Tom Hanks will agree to play Clarke, is who the hell is Haggis going to get to play President Bill Clinton? Damned if he isn’t right in the script, Arkansas accent, inquisitive mind and all. And in three good scenes.

Former National Security Advisor (and current Secretary of State) Condoleeza Rice is also a character with dialogue, and not a very sympathetic one. (No way around this — the facts are the facts.)

Vice-President Dick Cheney, National Security honcho Paul Wolfowitz and Clinton’s security adviser Anthony Lake are also characters, along with numerous other real-life figures. All with dialogue. Not as fictional stand-ins (as certain Clinton operatives were portrayed in Mike Nichols’ Primary Colors), but their literal selves.

Unfortunately, President Bush — who is certainly one of the villains of the piece, if you regard willful ignorance as a form of villainy — is an off-screen presence.

Against All Enemies is a riverting political drama — All The President’s Men meets Franz Kafka in the age of terrorism.

Every scene feels like it’s been chiselled and buffed to perfection (or at least my idea of that). And it has a sympathetic vulnerable hero (a government operator with no life who’s obstinate to a fault, and yet is a true vigilant soldier) and moments of warmth and humor and tragedy, and well-drawn secondary characters, and a finale that gives some 9/11 closure.

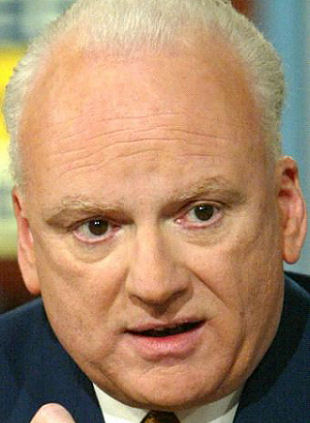

It’s about a dedicated hardcase lacking in certain diplomatic skills named Richard Clarke (Jason Robards would have been perfect in the mid ’70s, but right now Hanks-with-white-hair would be the absolute best choice) and his slow journey of discovery about what the Middle Eastern chess game is all about, play by play, and how the jihadists came to occupy and gradually rule the roost.

Scene by scene, act by act, Clarke keeps telling various government do-nothings what Middle Eastern terrorists might be up to, and nobody listens all that much. (Clinton’s people are more responsive than Bush II’s, but nobody acts brilliantly.) Then the Dubya do-nothings turn around after 9/11 and try to stick it to Clarke for being right.

Richard Clarke

It has a 24-page opening sequence that absolutely kills in terms of tension and psychological suspense, showing the White House staffers in turmoil on the morning of 9/11.

Then it rewinds back to start of Clarke’s government career in the late ’70s (when he was in his late 20s) and takes us on a journey of gradual discovery as Clarke learns more and more about the Mujahdeen, Islamic fundamentalists, offensive Jihad, “Usama” bin Laden and so on.

Then it’s back to 9/11 and Clarke’s confusion when the Bushies decide to use the attacks as an excuse to go to war with Iraq, and then his leaving the White House and writing his book and delivering his rant before a Congressional 9/11 committee, and finally his apology…even though he’s arguably the least guilty guy in the Washington establishment as far as 9/11 negligence is concerned.

Haggis told Waxman he hopes to turn Clarke’s book about “how we got ourselves into this mess” into a political thriller like All the President’s Men. “I don’t know how to do it, so that’s why I want to attempt it,” he explained. “It could be really embarrassing.”

If Hanks agrees to play Clarke (and he really should consider doing this — the film needs his good-guyness) and Against All Enemies is directed in the right way, with precisely the right pitch, it may indeed stand a chance of being compared favorably to All The President’s Men.

Okay, it’s a little wonky and it’s almost all about men and women in suits jawing with each other about intelligence and strategy, but it’s extremely tight and absorbing. I felt something hard, clean and special on every page.

The film is being produced by Haggis, John Calley and Larry Becsey with Colum- bia execs Doug Belgrad and Rachel O’Connor overseeing, as it were. Haggis didn’t give Waxman any hints about casting, but said “there’s a good list of people out there.”

Variety‘s Nicole LaPorte reported on 3.12 that Against All Enemies is “not necessarily” Haggis’s next project….but it should be. Nobody knows how long political films will continue to be hot in this own — better to strike when the iron is hot.

Clinton appears in three scenes between page 59 and 64, and he’s got a great scene on page 63 in which he comes off smart and resourceful and confident. And he laughs, and makes others laugh. He’s not the hero (that’s Clarke’s role) but Clinton is portrayed as a reasonably okay guy — a chief exec who gets it and sees the value in having a guy like Clarke nearby.

Vanderbilt’s script is so smart and sharp, and delivers so thoroughly in terms of authenticity, that the only actors on the planet who could sell the Clinton scenes would be either David Morse (a dead ringer) or John Tavolta, who of course played a character based on Clinton in Primary Colors . But even Morse or Travolta would feel a tiny bit wrong. To me, anyway.

I’m just going to say this: President Clinton should consider playing himself in this film. Seriously. He’d be great, he’d obviously be convincing and he’d be helping to recreate a very close approximation of the truth.

Besides the fact that a move like this would be the next logical step in the Holly- wood-Washington blender machine. Things have reached a point (remember those real-life Washingtonians taking to “drug czar” Michael Douglas in Traffic?) where a former President acting in a classy film like this would not be seen as all that curious. If you ask me it would have a kind of dignity.

Clinton cabinet

I asked for casting suggestions on Saturday, and here’s the best of them so far…

Richard Clarke: Tom Hanks, Phillip Seymour Hoffman, a slimmer James Gandolfini (looking to de-Soprano-cize his image by playing a wonky type).

Bill Clinton: Clinton himself, David Morse, John Travolta.

Dick Cheney: Jason Alexander (white hair, aged a little), Ben Kingsley.

Paul Wolfowitz: Alan Rosenberg, William H. Macy (a little make-up, hair coloring), Ron Silver.

Condoleeza Rice: Angela Bassett, Regina King, Merrin Dungey (from King of Queens/Alias/Curb)

Anthony Lake: Jude Ciccolella (excellent in 24 )