With the exception of Screen Daily‘s Stephen Whitty, the critics who’ve seen Joel Coen‘s The Tragedy of Macbeth via the New York Film Festival are not only admiring but in some cases highly enthused.

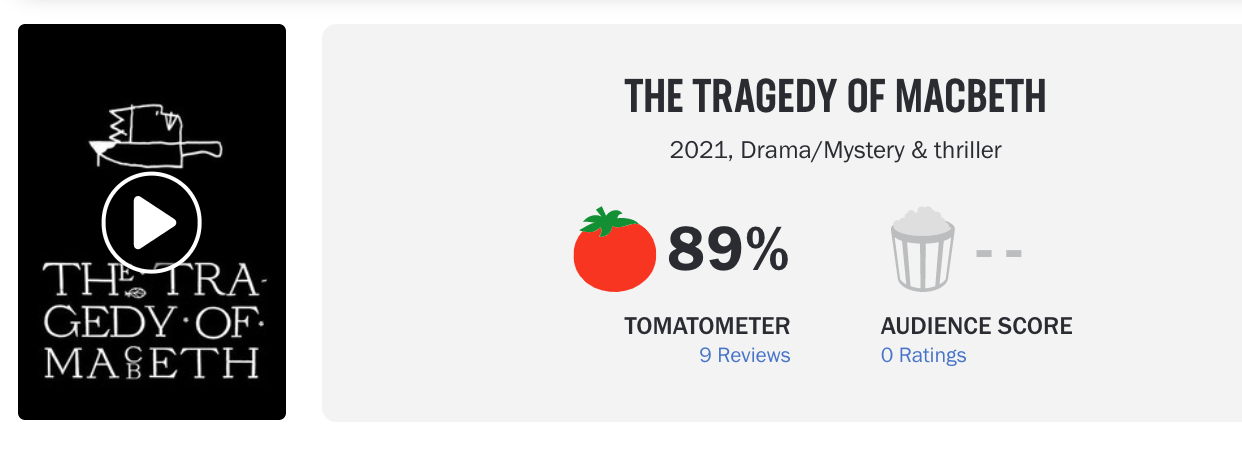

Right now both Metacritic and Rotten Tomatoes are posting 89% approval ratings.

How does this square with the fact that nothing came of a months-old screening for Cannes topper Thierry Fremaux, and the fact that the Venice Film Festival committee didn’t care for it, and declined to invite it to the recent 2021 gathering.

Variety‘s Owen Gleiberman and THR‘s David Rooney found Coen’s film impressive. To go by their reviews, The Tragedy of Macbeth sounds respectable enough. Perhaps not to everyone’s liking, but certainly a film with integrity and a certain scheme. And yet Venice turned it down.

Nonetheless something about these upbeat notices feels a tad suspicious. Robert Daniels calling it “definitely the bleakest adaptation” of Shakespeare’s tragedy prompts the inevitable “okay but why?” Macbeth isn’t bleak and bloody enough on its own? How does Coen’s decision to make his Macbeth stark and stripped down and lacerating…in what way does this approach enhance the material?

Roman Polanski’s 1971 version of this melancholy masterpiece was and is a knockout on so many levels, and yet critics at the time were partly dismissive because they didn’t care for Polanski having injected his own personal tragedy (i.e., the savage murder of his wife and her housemates two years earlier) into the film. And yet, perverse as this sounds, Polanski’s history gave his Macbeth an urgency and an attachment to the early ’70s zeitgeist; in this context very much alive.

What igniting element has prompted Joel Coen’s film other than wanting to give his gifted wife (Frances McDormand) a chance to play a great role? No Country for Old Men was a superb suspense film about a stalking killer, but it was also about a certain cultural poison that, in the view of original author Cormac McCarthy, had begun to infect the water table. What is informing Coen’s Macbeth in this sense? What’s the echo factor? Does it have one?

Friendo: “It’s no secret that pandemic-era film critics have veered towards hyperbole and over-praising certain films. I wouldn’t be surprised if that’s the case with Macbeth, but I’m very excited to see it. Visually, it looks stunning.”

Whitty: “Why this Macbeth, and why now – particularly after the handsome Fassbender/Cotillard teaming evaporated at the box office? It certainly adds another portrait to McDormand’s recent gallery of older women finally determined to finally live without compromise; it’s lovely, and loving, that her director husband would want to make this film for her. And Washington — who was charmingly regal in Branagh’s 1993 Much Ado About Nothing — deserves more chances to play Shakespeare.

“But Coen’s film doesn’t find a way to say anything fresh about politics, or ambition, while its gender dynamics — nagging woman finds fulfillment by living through husband — feel almost antique. Macbeth is more than 500 years old by now. Directors need to still make it feel new – or risk turning it into a poor play that struts and frets its hours upon the screen, and then is heard no more.”

Jordan Ruimy friendo: “Just saw this. Thought it was okay. It has its moments, but it didn’t work for me overall. Kathryn Hunter was great. The response to this feels kinda over the top from the critics.”