I’ve always loved Janet Maslin‘s writing, and especially her film reviews. She became a film critic for The New York Times in 1977, and then the paper-of-record’s top-dog critic on 12.1.94 when the long-serving Vincent Canby (1969-1994) moved on to theatre reviews.

Maslin covered the celluloid waterfront for five years, and to this day I vividly recall reading her Titanic review on the morning of 12.19.97, and a statement at the end of paragraph #2 that James Cameron‘s epic was “the first spectacle in decades that honestly invites comparison to Gone With the Wind.”

But Maslin’s run came to a halt after the Times published her enthusiastic review of Stanley Kubrick‘s Eyes Wide Shut on 7.16.99.

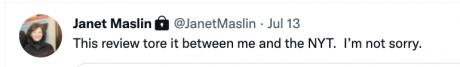

Yesterday Maslin tweeted that the Eyes Wide Shut review “tore it between me and the NYT…I’m not sorry.” I’ve never heard the detailed blow-by-blow about that episode, but I’d sure like it if Maslin (who’s been a Times book reviewer for the last 22-plus years) would tell it some day.

What other film critics have had a falling-out with their editors over their opinions, or even a single film review?

I seem to recall reading that Andrew Sarris‘s 8.11.60 review of Psycho, his very first for the Village Voice, got him into trouble, but not to the point of getting whacked. “I got so many angry letters about it,” Sarris recalled decades later. “It was my first Cahiers du Cinéma review, you might say. The idea that I promulgated [was] that Hitchcock was a major avant-garde artist. Everybody knew what Hitchcock did. Most people liked him, but didn’t take him seriously. So that was the beginning [of the auteur theory].”

In June 1976 Todd McCarthy was cut loose from the Hollywood Reporter over a negative review of Ode to Billy Joe. “I filed a dismissive review,” McCarthy wrote on 4.15.20. “[It] was published, but the next day got a call from my editor, B.J. Franklin, who conveyed the news that Jethro, otherwise known as Max Baer Jr., the director of the film, was not a bit pleased with my notice. Would I perhaps consider taking another look at it with an eye to revising my opinion upward?

“When I refused this opportunity, B.J. proposed that I interview Max about the film. I politely declined. The next day I was informed that my services would no longer be required at the Reporter, and also learned that Max and B.J. were Bel-Air-circuit social friends.”

In 1991 Washingtonian editor Jack Limpert vehemently disagreed with Pat Dowell‘s positive review of Oliver Stone‘s JFK. On 2.11.17 Washington Post columnist John Kelly wrote that “it’s not clear if Limpert showed Dowell the door or if she found it on her own.” Limpert later said that JFK was “the dumbest movie about Washington ever made.”

I experienced a fair amount of disapproval for my own Eyes Wide Shut review, although my feelings were quite different than Maslin’s.

Excerpts: “In a certain sense you could describe Eyes Wide Shut as a perfectly white linen tablecloth. That implies purity of content and purpose, which it clearly has. But Eyes Wide Shut is also a tablecloth that feels stiff and unnatural from too much starch.

“Just 7,was one of the great cinematic geniuses of the 20th century, but on a personal level he wound up isolating himself, I feel, to the detriment of his art. The beloved, bearded hermit so admired by Tom Cruise and Steven Spielberg had become, to a certain extent, a guy who didn’t really get the world anymore.

“Not that he wanted or needed to. He created in his films worlds that were poetically whole and self-balancing on their own aesthetic terms. But as time went on, they became more and more porcelain and pristine, and less flesh-and-blood. Eyes Wide Shut is probably the most porcelain of them all.

“The lesson is simple: If you want your art to matter, stay in touch with the world. Keep in the human drama, take walks, go to baseball games, chase women, argue with waiters, ride motorcycles, hang out with children, play poker, visit Paris as often as possible and always keep in touch with the craggy old guy with the bad cough who runs the news stand.

“What Kubrick chose to create is not being questioned here. On their own terms, his films are masterful. But choosing to isolate yourself from the unruly push-pull of life can have a calcifying effect.

“Kubrick was less Olympian and more loosey-goosey when he made his early films in the `50s (Fear and Desire, The Killing, Paths of Glory) and early `60s (Lolita, Dr. Strangelove). I’m not saying his ultra-arty period that began with 2001: A Space Odyssey and continued until his death with A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket and Eyes Wide Shut, resulted in lesser films. The opposite is probably true.

“I’m saying that however beautiful and mesmerizing they were on their own terms, these last six films of Kubrick’s were more and more unto themselves, lacking that reflective, straight-from-the-hurlyburly quality that makes any work of expression seem more vital and alive.

“So many things about Eyes Wide Shut irritate me. Don’t get me started. So many others have riffed on this.

“The stiff, phoney-baloney way everyone talks to one another. The unmistakable feeling that the world it presents is much closer to 1920s Vienna (where the original Arthur Schnitzler novella was set) than modern-day Manhattan. The babysitter calling Cruise and Kidman ‘Mr. Harford’ and ‘Mrs. Harford.’ (If there is one teenaged Manhattan babysitter who has ever expressed herself like a finishing school graduate of 1952 and addressed a modern Manhattan couple in their early 30s as ‘Mr.’ and ‘Mrs.,’ I will eat my Persian living-room rug.) The trite cliches that constitute 85% of Cruise’s dialogue. The agonizingly stilted delivery that Nicole Kidman gives to her lines in the sequence in which she’s smoking pot and arguing with Cruise in their bedroom. That absolutely hateful piano chord that keeps banging away in Act Three.

“I hope what I’ve written here isn’t misread. I’ll always be grateful to have lived in a world that included the films of Stanley Kubrick. He’s now in the company of Griffith, Lubitsch, Chaplin, Eisenstein and the rest. Prolific or spare, rich or struggling, lauded or derided as their artistic strivings may have been, they are all equal now.”