Sharon’s Book

The first thing that got me about Sharon Waxman’s Rebels on the Backlot (Harper Entertainment) was its assurance. It’s a very smooth and soothing read.

Call me a plebeian but I love inside-the-beltway books that deliver that massage-y, cruise-control, we-know-everything feeling (like Peter Biskind’s Down and Dirty Pictures and David Thomson’s The Whole Equation did) along with…you know, the other standard virtues.

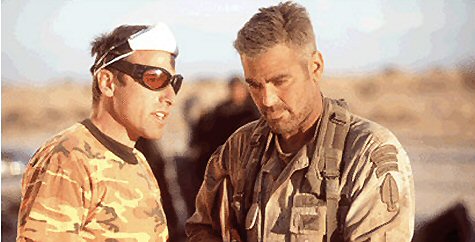

Three Kings director David O. Russell, star George Clooney during the problematic (some would say tumultuous) shooting.

The next thing that got me was a certain compassion for George Clooney and David O. Russell. Those poor guys…fine on their respective turfs, but put them together on the set of a physically difficult, hard-to-get-right movie like Three Kings and sparks of agitation are inevitable.

Waxman delivers a better, more convincing story of their fight during the making of this 1999 film than anything I’ve read or heard anywhere else.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

What was the trouble about? Russell, King’s director, told Clooney before shooting began that he needed to break a lot of bad acting “habits,” and that he wanted Clooney “to be very still” in his role. When Kings began rolling, Russell kept on Clooney to cut down on the Clooney-isms, in response to which the TV-series veteran repeatedly “bristled.”

“Their relationship seemed doomed,†Waxman writes. Clooney “felt undermined by his director and labored under the burden of knowing he was Russell’s last choice…this led to disastrous consequences.â€

Out-there guys like Russell are never a day at the beach, but David O. was only trying to bring about the aesthetically right thing. Clooney does have a lot of bad habits. That cool-smug-guy thing that he does all the time…don’t get me started. Russell may have been the provocateur in the breakdown of their working relationship, but Clooney needed — needs — what he was trying to dispense.

It was reported two or three months ago that Russell was upset with Waxman for making him seem slightly looney-tunes in her Times profile of his methods in the making of I Heart Huckabees. Many people agreed with him to some extent, but Waxman’s book has balanced the ledger sheet. To my eyes, she’s portrayed Russell as the most doggedly exacting and perceptive big-gun director in town.

Rebels on the Backlot is essentially a story about the adventures of six Gen-X writer-directors — leaders of the pack who defined a certain accomplished, provocative, well-funded hipness over the least ten years: Russell, Spike Jonze, Quentin Tarantino, David Fincher, Steven Soderbergh and Paul Thomas Anderson.

“I wanted to know about who they were,” Waxman told a New York Observer writer last week. “When you are talking about films that are so personal in their vision, you can’t help but wonder from what mind or personality [those pieces of work] sprang.”

Waxman was in Park City covering the Sundance Film Festival for the New York Times, for which she handles the Hollywood beat. I could have arranged some face-time with her myself (which would have made the piece you’re reading a better one), but the festival kept shoving me around and throwing me off my game.

I’ve run into these directors at one time or another, mostly in the course of doing this or that story, but I’ve never gotten to know them. Not like I know Wes Anderson, say. (I’m wondering why Waxman didn’t include him in the book. Wes pushed to the front of the pack in the mid ’90s, and is as important as any of these other guys…no?)

Another thing I found delightful about Waxman’s book is that it conveys facts that significantly add to my understanding of what these filmmakers are about…what’s driven them, scared them, briefly defeated them, inspired them.

Rebels on the Back Lot author Sharon Waxman signing books at (I think) the party thrown by Harper Entertainment in Park City during the Sundance Film Festival.

I was shocked, shocked to read that Quentin Tarantino’s background was not that of a white-trash, fast-food-eating Tennessee kid from a broken home, but one that was more or less upper middle-class.

There’s a passage about Tarantino and Steven Soderbergh’s personal lives that I find fascinating. Partly because this is exactly the kind of passage that an aggressive and brilliant male writer would never include in a book about Hollywood filmmakers. It’s mildly cool nonetheless that Waxman has shown her colors in this fashion.

Tarantino nor Soderbergh “had trouble with intimacy” and “seemed [unable] to sustain relationships with the opposite sex,” she writes.

There was “a quiet woman” who was part of Tarantino’s life about 12 or 14 years ago named Grace Lovelace “who remains -– according to many who know [Tarantino] — the true love of his life.” She reports that after he became famous Tarantino became “a serial dater of his leading ladies or his producer or the starlet of the moment.”

This is nothing compared to what she does to Soderbergh. She suggests that he may be James Spader in sex,lies and videotape, “the articulate intellectual dealing with emotions in distant, muted ways,” a guy, like Spader’s “Graham” character, “who could enjoy sex with women only through the distance of the camera eye.”

To varying degrees, all the directors in Waxman’s book come off as fickle, egoistic, thin-skinned, prickly, brusque. This is nothing strange, of course. There’s always seemed to be a basic disconnect between submissive, mild-mannered, go-along behavior and being possessed of exceptional talent, smarts and vision. I’ve noticed this time and again, and it’s no big deal.

Some day, somehow, someone will discover on what set this shot of Steven Soderbergh was taken. My guess is The Limey.

A strong director can’t be a strong director without being tough and flinty and even unyielding. The game that requires toughness and tough hides. I respect this, and have no problem with anyone who wants to get in my face and give me an argument of some kind about something I’ve written. As long as they’re straight about it, fine.

A week and a half ago Soderbergh lectured me during the Inside Deep Throat Sundance party. It was about my writing a couple of years ago that George Clooney’s Confessions of a Dangerous Mind seemed strongly influenced by Soderbergh-ian visual stylings, which, in his view, diminished Clooney’s rep by suggesting he had no visual chops or chutzpah of his own.

I wish more people in this town would play it like Soderbergh and just walk right up and say it to my face.

It may sound like a vague put-down to call Rebels a great airport lounge or a coast-to-coast read, but this book is friendly. I read it cover to cover, but it’s structured and titled in such a way that you can just drop into any chapter and go to town. I guess what I’m really saying is that people with attention deficit disorder will have no problem with it.

More Later

New stuff, I mean. In the meantime, I’m holding on to some of the stories I ran last weekend at the Santa Barbara film Festival…

Panel Thief

Maybe a story about the intoxicating elements within a certain woman’s personality isn’t exactly page-one material, but Oscar screenwriting nominee Julie Delpy (for her Before Sunset collaboration with Richard Linklater and Ethan Hawke) totally killed at Saturday’s screenwriter’s panel at the Lobero Theatre.

Delpy is — right now, in my humble opinion — the absolute coolest, wittiest and most radiantly attractive actress around. Her Sunset performance had me half-convinced of this, but yesterday’s panel dazzle brought the house down and amounted to a total closer.

Actress-screenwriter Julie Delpy during Saturday afternoon’s panel discussion, “It Starts With the Script,” at the Santa Barbara Film Festival.

She was quick, hilarious and unabashedly confessional. Her mind was here, there and everywhere…but always amusingly and never scattershot. She said at one point that she’d lost the ability to think because she was listening too much to the sound of her own voice, and she had everyone in stitches as she described the disorientation. She unintentionally reduced moderator Frank Pierson to a straight-man stooge during a brief back-and-forth. Her facial expressions alone were inspired.

And she got off a great line about how women will have truly secured their just portion of power in the film industry “when a mediocre woman is given a powerful job.”

Brian Grazer and Ron Howard erred in not hiring Delpy to play Sophie Neveu opposite Tom Hanks in the forthcoming production of The Da Vinci Code. (They’ve gone with 26 year-old Audrey Tatou, who’s too young and small and slender to play Hanks’ pseudo-love interest…he probably outweighs her by at least 100 pounds.)

Garden State director-screenwriter Zach Braff was asked the most questions and drew the heartiest applause during yesterday’s discussion, as a good chunk of the audience was composed of under-35 types, the demographic that has turned Garden State into a formidable nationwide hit.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind screenwriter Charlie Kaufman and The Incredibles director and co-writer Brad Bird seemed to be the most popular after Braff, and all three delivered the best cracks.

(l. to r.) Screenwriters John Logan (The Aviator), Jose Rivera (The Motorcycle Diaries), Paul Haggis (Million Dollar Baby), Julie Delpy (Before Sunset), Frank Pierson (Dog Day Afternoon), Brad Bird (The Incredibles), Zach Braff (Garden State), Bill Condon (Kinsey), and Jim Taylor (Sideways) just prior to Saturday afternoon’s panel discussion at the Santa Barbara Film Festival.

That is, if you left Delpy out of the equation.

The other screenwriter panelists were Million Dollar Baby‘s Paul Haggis, Kinsey‘s Bill Condon, The Aviator‘s John Logan, Sideway‘s Jim Taylor,and The Motorcycle Diaries‘s Jose Rivera.

Pierson (Cool Hand Luke, Dog Day Afternoon), the current president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, got shouted down at one point by an audience member because they thought he was talking too much and not letting the panelists have their say. Pierson’s moderating skills can be on the avuncular and loquacious side, but he’s also a wise and perceptive man.

A very young aspiring screenwriter — a woman — asked Braff at one point whether “this feeling of uncertainty and nervousness and not knowing what’s going to happen in my life…is this going to continue or get worse or what?” Braff said he was sorry but no, it’s not going to stop, but hang in there and don’t let it defeat you.

Pierson had a better answer. He said to the woman, “If you’re lucky, it will never stop…because your writing will be better for it.”

Elvis Mitchell interviewing Sideways star Paul Giamatti at Santa Barbara’s Victoria Threatre late Sunday afternoon — 1.30.05, 5:45 pm.

Leonardo DiCaprio addressing crowd at Santa Barbara’s Arlington Theatre after being presented with the SBIFF’s Platinum Award by Aviator director Martin Scorsese — Sunday, 1.30, 9:20 pm.

Piece of letter-sized paper taped to seventh-row seat at Santa Barbara’s Arlington Theatre — Sunday, 1.30.05, 7:25 pm.

Author, film critic and TV personality Leonard Maltin and Best Supporting Actress nominee Virginia Madsen (for Sideways, as if I had to say that) after a small luncheon at Nu, a restaurant on State Street, which followed a women’s filmmaker panel at the Lobero Theatre — 1.30.05, 2:25 pm.

Santa Barbara Film Festival artistic director Roger Durling just before Saturday evening’s Annette Bening tribute — 1.29.05, 7:25 pm.

Former New York Times critic and current Columbia consultant Elvis Mitchell interviewing Best Actress nominee Annette Bening (Being Julia) at Santa Barbara’s Lobero Theatre — 1.29.05, 8:35 pm.

Woody Time

I drove up to the Santa Barbara Film Festival late Friday afternoon, checked into a Holiday Inn and went straight to the Arlington Theatre on State Street to catch the festival’s opening-night attraction — Woody Allen’s Melinda and Melinda.

Most of the reviews out of Europe (it played last fall at the San Sebastian Film Festival and has since opened commercially in Spain and other territories) called Melinda a return to form for Allen, and I seem to recall someone saying it was his best since Mighty Aphrodite.

That’s close to an accurate statement, or at least not far off the mark. Melinda and Melinda is a very good…make that a slightly-better-than-very-good Woody.

(l. to r.) Will Ferrell and Radha Mitchell in Melinda and Melinda.

It’s a half-downerish, half-amusing piece about the fine line between comedy and tragedy. It basically says that the two opposite poles are made of the same story material, and the difference essentially lies in the attitude we bring to this or that situation or circumstance.

The piece is framed by a couple of playwright/screenwriter pals (Wallace Shawn, Larry Pine) discussing the differences between comedy and tragedy. They expound by talking about a real-life story they’ve heard about an actual New York woman named Melinda (who’s known to a friend of theirs), and riffing on how her story might turn out as a tragedy or comedy.

These writers proceed to entertain each other by telling parallel tales about Melinda (which we see dramatized, of course) that are similar in every respect except for the fundamental slant.

Only Melinda (Radha Mitchell) appears in both versions. The downer piece costars Chloe Sevigny, Johnny Lee Miller and Chiwetel Ejiofor (the doctor from Dirty Pretty Things) while the comedic piece costars Will Ferrell and Amanda Peet.

The two stories explore themes and plot turns that Allen fans will quickly recognize. Anxious and lonely New Yorkers, lovers at cross purposes, spouses cheating on each other, and the constant dodging and lying that goes on between significant others.

“Of course we communicate,” Peet says to Farrell, her live-in partner, at one point. “Now, can we not talk about it?â€

I wouldn’t quite place Melinda among Allen’s very best (Manhattan, Crimes and Misdemeanors, Hannah and Her Sisters, Husbands and Wives). I would, however, put it in roughly the same realm as, say, Sweet and Lowdown or Bullets Over Broadway.

It’s not quite a nine-course meal, but is undeniably nutritious. It’s been written with a fairly sharp quill, gets right down to business in short order, and delivers the philosophical goods, gags and witticisms in an agreeably absorbing fashion.

It provides Mitchell, who portrays two versions of the same character of Melinda, with a chance to shift between Bergmanesque edge-of-suicide emoting and Annie Hall-like bubbly-goofy stuff, and she delivers with assurance and buoyancy on both counts.

And Ferrell has fun playing the neurotic, emotionally frustrated, wittily judgmental Woody character. The idea of an actor hired by Woody Allen to deliver a performance that literally channels Allen’s spirit and personality will always be an extremely weird confection, but Kenneth Branagh and John Cusack have obviously done it before and I suppose we’re all getting used to this.

The comic highlight is a would-be seduction scene between Farrell and Vinessa Shaw (the prostitute in Eyes Wide Shut). The gags in this scene aren’t profound, but they’re funny as hell.