I caught Rory Kennedy‘s Last Days In Vietnam a couple of months ago at the L.A. Film Festival. It held me, got to me, melted me down. It’ll air next April on PBS’s American Experience but please, please see it theatrically when it opens around the country in September and October (New York’s Sunshine and Lincoln Plazas on 9.5, L.A.’s Nuart on 9.19, the S.F. Bay Area on 9.19). Trust me — it’s a truly exceptional doc. My only beef is that Kennedy should have spoken to some former North Vietnamese combatants and government guys and gotten their perspective.

“I felt profoundly moved and even close to choking up a couple of times while watching Last Days in Vietnam yesterday at the Los Angeles Film Festival,” I wrote on 6.13. “The waging of the Vietnam War by U.S forces was one of the most tragic and devastating miscalculations of the 20th Century, but what happened in Saigon during the last few days and particularly the last few hours of the war on 4.30.75 wasn’t about policy. For some Saigon-based Americans it was simply about taking care of friends and saving as many lives as possible. It was about good people bravely risking the possibility of career suicide by acknowledging a basic duty to stand by their Vietnamese friends and loved ones (even if these natives were on the ‘wrong’ or corrupted side of that conflict) and do the right moral thing.

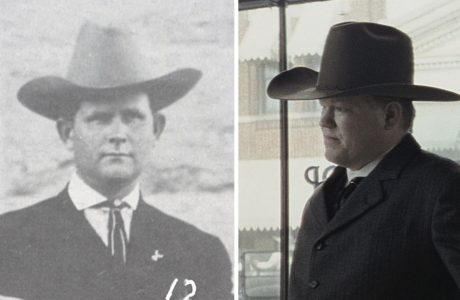

“Kennedy’s incisive, well-sculpted (if not entirely comprehensive) 98-minute doc is basically about how a relative handful of Americans stationed in Saigon — among them former Army Captain Stuart Herrington, ex-State Department official Joseph McBride and former Pentagon official Richard Armitage — did the stand-up, compassionate thing in the face of non-decisive orders and guidelines from superiors (particularly U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam Graham Martin) who wouldn’t face up to the fact that the North Vietnamese had taken most of South Vietnam by mid-April and would inevitably conquer Saigon. It was obvious as hell to almost anyone with eyes and ears, and yet Martin and other officials, afraid of triggering widespread panic, wouldn’t approve contingency plans for evacuation until it was way, way too late. So the above-named humanitarians and their brethren decided it was ‘easier to beg for forgiveness than to ask permission’ and did what they could — covertly, surreptitiously, any which way — to save as many South Vietnamese as they could.”