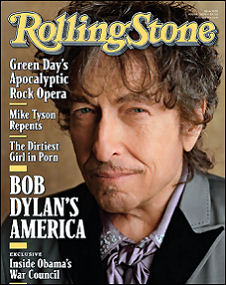

At some point in Douglas Brinkley‘s “Bob Dylan’s America,” a Rolling Stone cover story keyed to Dylan’s new album “Together Through Life,” is a passage about director John Ford. And I have to be honest and say that it bothers me somewhat.

cover of current Rolling Stone; director John Ford.

“At heart Dylan is an old-fashioned moralist like Shane, who believes in the basic lessons taught by McGuffey’s Readers and the power of a six-shooter. A cowboy-movie aficionado, Dylan considers director John Ford a great American artist. ‘I like his old films,’ Dylan says. ‘He was a man’s man, and he thought that way. He never had his guard down. Put courage and bravery, redemption and a peculiar mix of agony and ecstasy on the screen in a brilliant dramatic manner. [And] his movies were easy to understand.

“I like that period of time in American films. I think America has produced the greatest films ever. No other country has come close. The great movies that came out of America in the studio system, which a lot of people say is the slavery system, were heroic and visionary, and inspired people in a way that no other country has ever done. If film is the ultimate art form, then you’ll need to look no further than those films. Art has the ability to transform people’s lives, and they did just that.'”

Yes, of course — the director of The Grapes of Wrath, The Informer, How Green Was My Valley, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, The Horse Soldiers, Drums Along the Mohawk and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance was a superb visual composer and one of Hollywood’s most economical story-tellers bar none. His films were always layered and ripe with sub-currents that never flowed in one simple direction. His films always seemed fairly obvious and sentimental…at first. Then you’d watch them again and reconsider, and they always seemed to be about a lot more.

Except being a man’s man only goes so far. And I’m disturbed by Dylan being either oblivious to or deliberately overlooking the John Ford downside. The occasional staginess and jacked-up sentiment in just about every one of his films. The Irish clannishness, the tributes to boozy male camaraderie, the relentless balladeering over the opening credits of 90% of his films, the old-school chauvinism, the covert racism, the thinly sketched women, the “gallery of supporting players bristling with tedious eccentricity” (as critic David Thomson put it in his Biographical Dictionary of Film), and so on.

How could the guy who wrote “the ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face” not at least acknowledge the conflict between the majestic Ford and the whorish Irish sentimentalist? It’s depressing to consider a man who “once held mountains in the palm of [his] hand” being content to rely upon a distillation of a classic frontier ethos as the bedrock of his philosophy. I realize Dylan is a big Barack Obama fan, but it bothers me to think of him as a bit of a cultural conservative. Because Shane isn’t about old-fashioned morality, dammit. It’s nominally about a heroic, stand-up figure in buckskin, yes, but it’s really about a man grappling with — resisting — his basic nature only to finally give in to it at the end.