The Big Stink

Deep down there’s something in us that enjoys the art of financial hoodwinking and flim-flamming… as long as it’s presented in a suitably fictional and charming package.

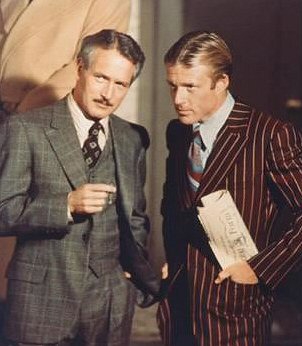

There’s an appealing example of this in The Sting when Paul Newman’s Henry Gondorff is talking about his days with the O’Shea mob in Chicago in the 1920s, when corruption was rife and “the feds took their end without a beef.”

(l. to r.) Former Enron CEO Kenneth Lay, former COO Jeff Skilling, sullied execs Andy Fastow and Lou Pai

And then Newman’s smirk grows into a shit-eating grin as he says to Robert Redford’s Johnny Hooker, “And it really stunk, kid.”

If you’re honest, you’ll admit your reaction when you first saw this scene was something along the lines of “yup…corruption can smell like nectar when there are no squealers and everyone’s equally dirty” or “there’s something to be said for graft and payoffs if they’re handled in a civilized manner.” Right? Especially if guys like Newman are in on it.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

In real life, of course, financial snookery isn’t quite as sexy.

Nine times out of ten the grifters are high-end corporate types with fleshy faces and boring haircuts and heavy political connections and an ability to put people to sleep with their inane remarks at stockholder’s meetings, or in their statements to the press.

And so it was with the Enron meltdown that began to break about four years ago, and spilled over into total scandal in early ’02.

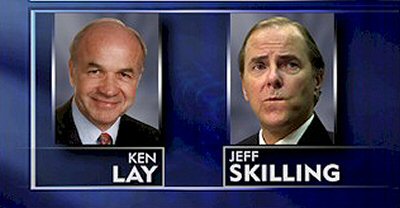

Nothing remotely charming in this mess. The leading Enron bad guys, CEO Kenneth Lay and COO Jeff Skilling, were just odious. And yet Alex Gibney’s Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (Magnolia, 4.22 in New York and Houston, expanding on 4.29) manages to make their story a gripping thing.

It is, in fact, fully entertaining, and I never thought I’d say that about a documentary recounting the wrongdoings of a bunch of George Bush-supporting pirates.

“It’s like a heist film,” Gibney told me earlier this week. “When you think of it that way, it takes on a certain dimension.”

Over-valued and increasingly founded on imaginary concepts as it got closer and closer to the financial precipice, the Houston-based Enron, which got rolling in the `80s as as a gas-pipeline energy company but began to get into all kinds of stuff in the late `90s, was this country’s seventh-largest corporation before collapsing in 2001.

Lay, Skilling and other bigwigs walked away with over a billion dollars in their pockets, leaving lower-level investors and employees holding the bag, in some cases with their life savings wiped out.

Gibney has based his film on the 2003 bestseller of the same name, co-written by Fortune magazine reporters Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind. He began working on it just over a year ago and finished it last Thanksgiving,

(l. to r.) Skilling, Lay and former Enron executive Joseph Sutton.

Enron adds new reporting about stuff that has come out since ’03, including some indictments that have come down. The feds are putting Lay and Skilling on trial for fraud in January ’06. If they get a conviction, stiff sentences may result.

There is also TV coverage of Congressional hearings, several on-camera recollections from eyewitnesses and various folks who got burned. Lay and Skilling didn’t talk to Gibney but their statements are covered with TV news footage, C-SPAN clips and corporate videotapes originally meant for in-company viewing.

The basic message is that as things got more and more vision-driven in the mid to late ’90s, Enron became an absurdly overvalued company. Its stock was pumped up by deceptive maneuvering, and it borrowed heavily to make itself look good to the world, and eventually the fakery couldn’t sustain itself.

In ’91 Skilling introduced one of his cuter moves, which he got SEC approval on, called “mark to market” accounting. It was a scam by which Enron could project millions of dollars in potential profits from some newly launched endeavor or acquisition in their stockholders reports. If the venture wasn’t profitable, Enron was obliged to cover the losses with heavy borrowing.

A key component in all this, Gibney says, is that Enron wasn’t hassled all that much by federal oversight agencies, partly, he feels, because of a certain chumminess between Lay and George Bush, who accepted millions in Enron campaign contributions. Enron’s freedom to pretty do what it wanted to do seemed linked in a lot of people’s minds to an attitude on Bush’s part to go easy on “Kenny Boy” and his pals.

It turns out Enron was behind the big California energy crisis of 2000 and ’01. As footage of California brush fires are shown in the film, tapes are heard of Enron guys chortling about the success of their plan to artificially create the crisis. This was partly achieved by selective “maintenance” shut-downs of power plants, which allowed for hikes in electricity rates.

Former California governor Gray Davis, whom Enron tried to blame for the rolling blackouts that were happening back then, is shown trying to point the finger at Enron. Gray “suspected something [like this] was going on but he couldn’t prove it at the time,” says Gibney. “When 50% of the power plants were down for maintenance on a single day, you have to wonder what’s going on. That smelled fishy.”

Enron suggests that a May ’01 conference between Lay and eventual California gubernatorial candidate Arnold Schwarzenegger gave the latter information that he used to make Gray look bad over his handling of the energy crisis.

The one note of compassion (or at least empathy) comes when the doc briefly focuses on Lou Pai, a Skilling associate who had a yen for strippers and strip clubs. It reminded me of Mort Sahl’s crack that revelations in the early ’80s of sexual impropriety by a certain Republican fat cat was “a cynical attempt to humanize the Reagan administration.”

The most chilling scene for me happens during a morale-boosting meeting among Enron employees right when the meltdown is happening, and some guy asks if he should invest all of his money, “all of my 401 K” in Enron, and he is told by a spokeswoman who happens to be standing at the mike, “Absolutely!” And then she laughs.

Bottom line: a lot of people were being paid a lot of money for working with Enron and being good team players, and as long as the checks were coming in none of them wanted to know anything. Nobody being paid good money ever does.

An Enron employee named Cliff Baxter killed himself in January ’02.

How much did Lay and Schilling walk away with? In the film Lay is quoted as saying he’s down to his last $20 million and something like $1 million in liquidity. Skilling reportedly paid $23 million to his attorney as a retainer fee.

Andrew Weissman is heading the prosecution of Lay and Skilling in the upcoming fraud trial. He was also the lead attorney in the government’s prosecution of fraud charges against the Arthur Andersen accounting firm, which cooked and then shredded the books for Enron during its big-calamity phase.

The Justice Department has been investigating the Enron debacle since January 2002. Why has it taken so long to put together a case against Lay and Schilling? “Because it’s very complicated,” says Gibney. “It’s going to be very tough to try because they’re going to have to prove intentional fraud. They may be found not guilty.”

President Bush “is, I think, happy to have the Department of Justice pursue this case as aggressively as possible. Now he can just say ‘I didn’t know’ and if they did something crooked, they have to pay the price.”

Gibney says “if I were king of the world, and it’s probably a good thing that I’m not, I’d like to see Ken Lay work as a grill man for McDonald’s and be forced to ride only public transportation for the rest of his life.”

Here’s a link to Bethany McLean’s 3.5.01 Fortune magazine piece, “Is Enron overpriced?”

If McLean’s piece has a money paragraph, it’s this: “‘Enron is an earnings-at-risk story,’ says Chris Wolfe, the equity market strategist at J.P. Morgan’s private bank, who despite his remark is an Enron fan. ‘If it doesn’t meet earnings, [the stock] could implode.'”

Fortune has put up a special webpage linking to various other aspects of its Enron reporting.

The thing that sticks with you at the end of Gibney’s film is the look in Lay and Skilling’s eyes as they try to sell the concept of Enron’s financial health.

I don’t know if these guys would have gotten off any easier if they had some of that Henry Gondorff charm, but I know audiences tend to respond to this on all sorts of levels.

If I had been an Enron stockholder five or six years ago in a buy-sell position, and all I had to go on was the way these guys presented themselves and the deep-down attitudes they conveyed, I would have unloaded like that. I feel sorry for the people who kept their Enron stock and lost everything, but that’s life in the big city.

Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room “is kind of a moral report card,” says Gibney. “There is a moral dimension to our economy that has to be reckoned with. It says, in a way, that the free market ultimately makes us slaves….utterly free but slaves at the same time.”

HDNet, the high-definition cable station owned by Enron producers Mark Cuban and Philip Garvin, will screen Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room concurrent with the 4.22 theatrical debut. It will play at 8 pm eastern (5 pm Pacific) and then at 11 pm eastern (8 pm Pacific).

Bill of Goods

The thing that made me want to buy Universal Home Video’s new 2-Disc Anniversary Edition of Apollo 13 was a promise on the jacket art that the IMAX version of this 1995 film is included on the second disc.

I saw a piece of the IMAX version on this Ron Howard film at a special invitational press screening a couple of years ago, and it made the images look sharper, fuller and bolder than those in the theatrical version, which was pretty good to start with.

The IMAX version looks better because each frame of the original has been digitally tweaked so as to make everything look richer and more vivid, in order to meet the blown-up standards demanded by the much larger IMAX screen.

Actual frame of IMAX film, indicating the appproximate 1.33 to 1 aspect ratio in which IMAX films are projected in theatres…

I wondered at first how this would work since the aspect ratio of an IMAX screen is kind of boxy (close to 1.33 to 1), and Apollo 13 was originally released in Scope (2.35 to 1). The solution, I learned at the press conference, is that Apollo 13 was actually shot in Super 35mm, which captures a 1.33 to 1 image but is then cropped in post-production to create a Scope aspect ratio. So there was plenty of extra top-and-bottom image space to fill the IMAX frame.

Pretty much all Scope films are shot in super 35, or so I’ve heard. This is how DVD pan-and-scan versions of Scope films are assembled — not by cropping off the sides of the Scope image but by using the original 1.33 to 1 super 35 image.

Anyway, knowing all this I was shocked when I played the IMAX version last night and discovered it’s not the IMAX version at all. What Universal Home Video has released on Disc 2 is a cropped IMAX image with an aspect ratio that looks roughly to me like 1.75 to 1.

(A critic on www.dvdtalk.com wrote that the IMAX DVD version uses a 1.66 to 1 aspect ratio. He’s wrong. Check out the Warner Home Video DVD of Barry Lyndon — that’s 1.66 to 1.)

I’m not strenuously complaining about this. Image quality-wise the IMAX-on-DVD version of Apollo 13 looks quite superb. It has a knock-down, almost startling clarity and all kinds of ripe bountiful colors. It is so appealing and soothing to the eye that I stopped working last night in order to watch it.

But — but! — to tell DVD buyers they’ll be getting the IMAX version of this film when they buy the new DVD is a cheat. It’s the IMAX image quality without the actual shape of the image shown in IMAX theatres, and in my book to sell it as a “the IMAX Experience version” is at least a half-lie. To me it’s a flat-out fib.

…and the 1.75 to 1 aspect ratio of the “IMAX Experience” version as presented on the new Apollo 13 2-Disc DVD.

I enjoyed Apollo 13 when it came out ten years ago, but I hadn’t looked at it again since last night and it plays better than I remember. Well shot, professionally paced and believably acted, this is a fully involving, methodical recreation of a true-life event. I still love Dean Cundey’s photography and while the special effects look a bit dated by today’s standards, they’re still decent.

It’s always the mark of a good film when the third-act tension (i.e., will the possibly damaged heat shield hold during re-entry?) in the third-act works even when you know astronaut Jim Lovell (i.e., Hanks character) and the other two guys made it and there’s nothing to worry about.

I had forgotten how young Hanks used to look, and how thin he once was. Kevin Bacon looks so much younger also; ditto Bill Paxton. I know it sounds banal for an industry journalist to mention age and weight issues, but this is the first thing you notice when you watch this DVD. You say to yourself, “Wow, time really moves along.”