Oh, to have been gay and feisty and lucky enough to have been at the Stonewall Inn in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, which is where and when the gay rights movement began. You can’t “nice” people into abandoning oppression or prejudice. You have to tell them to stop it, and nothing says “no” like a little street action. Shoves, shouts, cuts, bruises and broken glass have a way of getting right to the point.

Instead of accepting a typical rousting by the NYPD for the crime of being themselves, the patrons at this West Village bar at 53 Christopher Street hit back. They fought, jeered, threw beer bottles, broke windows, and persuaded the arresting officers to take refuge in the bar out of concern for their own safety. A few more nights of disturbances followed, and it was clear to those on either side that things would never be the same. A year later the first Gay Pride parade happened, and the long drip-by-drip process of de-prejudicing straight American began.

Homophobia obviously lives some 40 years later. In early May an Obama adminstration spokesperson referred to rumblings about Supreme Court nominee Elena Kagan possibly being gay as a “charge.” But it’s a different country now than it was back then, significantly, and it’s a real emotional pleasure to savor the spirit of awakening and revolt that the Stonewall riots signified, if only to grasp the changes that have happened and the upheavals that were required.

This is what Kate Davis and David Heilbroner‘s Stonewall Uprising — a doc based on David Carter‘s “Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution” — does for the average viewer, gay or straight. It takes you back to the bad old days and shows what it was like to be gay in the ’50s and ’60s (“There was no out — there was only in,” as one veteran recalls) and allows for a sharing in that flashpoint Stonewall moment.

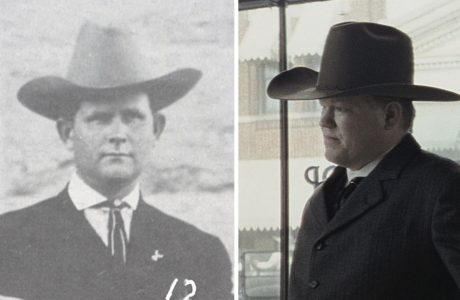

(l.) Stonewall Uprising co-director Kate Davis, (r.) director John Cameron Mitchell (Shortbus, Hedwig and the Angry Inch) during Stonewall Inn after-party following last Wednesday’s premiere screening at Film Forum.

David Heilbroner, Davis, Mitchell.

The chief accomplishment of Stonewall Uprising is the concise delivery — the discipline and tight editing and impassioned, first-person recollections that provide a blow-by-blow, hour-by-hour history of how that night unfolded. I was in the grip of it from the beginning. I got a kind of contact high from it, in a way. I recommend the film to anyone with the slightest interest in the ’60s rebelllion dynamic, or who simply wants to learn a few things about the Stonewall convulsions without buying Carter’s book.

I remember talking to an older actor in the late ’80s who wasn’t exactly enlightened in his view of homosexuality, but he once confessed that he respected — feared — the anger of gay people. “Those guys are brutal,” he said. “You don’t ever want to mess with the fags…whew. They’re like hornets.” I don’t think too many older homophobes had that trepidation before Stonewall.

It’s fascinating to consider how homosexuality was generally seen in the mid to late ’60s. It really was the Pleistocene era. Consider this 2.12.65 article in Time magazine called “Psychiatry: Homosexuality Can Be Cured,” and this May 1967 article in Harper’s magazine, “A Way Out for Homosexuals,” by a “curing” proponent named Dr. Samuel B. Hadden. Or The Detective, the 1968 Manhattan melodrama in which Frank Sinatra‘s character, portrayed as relatively decent and humane in his attitude toward gays, says at one point that “these people are sick.”