Susanne Bier‘s Things We Lost in the Fire (Dreamamount, 10.19) is like a thousand emotional wind-chimes made into a quiet symphony. It’s my idea of a flat-out masterpiece, certainly within the realm of the family-tragedy drama. Bier knows exactly how to make every moment feel true and on-target, and Benicio del Toro‘s lead performance as a heroin addict struggling to recover and stay that way is the best I’ve seen this year from anyone of either gender, country or classification. Yeah, that’s what I said.

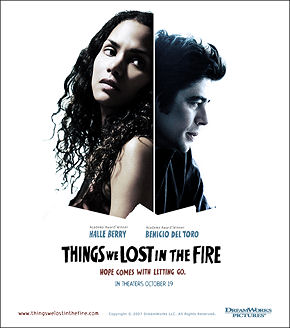

Benicio del Toro in Things We Lost in the Fire

I saw Bier’s film yesterday afternoon and came out weak-kneed. I knew it was doing something really right and dead-center five minutes in. Films about healing and recovery (the oppressors in this case being grief and drug addiction) can sound dreary as hell when you read the capsule descriptions, but there are some that settle down into themselves and strike deep, sonorous chords (in the vein of, say, Ordinary People, which isn’t as subtle and carefully shaded as this one). Add the curious but unmistakable chemistry of spot-on performances (i.e., the ones that never seem to try to do anything but wind up doing everything) and you’re left with something that can feel almost miraculous.

Dreamamount is sitting on Things We Lost in the Fire like a chicken sits on an egg. Bluhhhhck! They’re keeping it warm and protected, but they’re not exactly doing the old ballyhoo cartwheel. I’m guessing that the film hasn’t played all that strongly with Average Joes (i.e., a distaste for stories dealing with drug users?), and that reactions from critics haven’t been universally ecstatic (despite others having had reactions similar to mine), and that a logical decision has been made by marketers to (one deduces) put a cap on spending. Promote the film modestly, put it into theatres two weeks from now, and let it die.

Good smallish films like Things We Lost in the Fire are faintly promoted to death all the time by big-studio marketing departments, who are best (here we go with the cliche) at selling “event” movies, tentpolers, comedies. A movie like Bier’s should probably be released by a TLC outfit like Picturehouse or Fox Searchlight or ThinkFilm or Sony Classics. Movies this good should somehow be given flight. I only know I’m not feeling the presence of this film anywhere (not from ads or from fellow journalists…nothing), and it makes me want to kick something.

I don’t care what others may be saying. I know it when I’ve seen something truly exceptional. Movies about small emotional brewings that gradually turn into magic potions simply don’t get any better than this.

And there can be no beating around the bush about Del Toro’s performance as Jerry the junkie, a once-successful lawyer who’s slid down into the pit. Over the course of this two-hour film he climbs out of his drug hole, brightens up, chills out and settles in, relapses, almost dies, and then gradually climbs out of it again. I’m starting to see this actor (whom his friends and Esquire magazine profilers call “Benny”) as almost God-like. He’s holding bigger mountains in the palm of his hand, right now, than De Niro held in the ’70s and ’80s. He’s one of the top four or five superman actors we have out there. There isn’t a frame of his performance that doesn’t hit some kind of behavioral bulls-eye.

I’ll tell you this — when journalists who’ve seen Things We Lost in the Fire go “I don’t know…meh” and then say in the same breath that some other so-so film is “pretty good” there’s some kind of virus out there that I don’t want to give a name to.

I know that at least two critic friends (one of whom I saw it with yesterday) aren’t big fans. But this is a film that’s been kissed by something. Bier (Open Hearts, Brothers, After The Wedding) is a master of intimacy and soul-searchings that feel un-rhymed and.uncalculated, but which really sink in. The behavior in her films never seems pushed or “performed,” and this is no exception. There’s no question in my head that Fire is her best ever.

I’m really not understanding the subdued response so far to Del Toro’s perform- ance. He might floor everyone next year with his Che Guevara in The Argentine and Guerilla, but Jerry is the best thing he’s done up to now — twitchier than Fenster in The Usual Suspects, weaker and more vulnerable than Javier Rodriguez in Traffic, less ravaged and down-heady than Jack Jordan in 21 Grams.

And Halle Berry has saved her career with her fine performance as Audrey, a Seattle-based mother of two who loses her husband Brian (David Duchovny, rejoicing in his best part since The Rapture), a very successful architect and house-builder, to an act of idiotic violence one night. It’s easily her finest work since Monster’s Ball.

Audrey isn’t a weakling, but she’s prone to emotionally needy behavior at times. Her kids, a six year old buy named Dory (Micah Berry) and a ten year old girl named Harper (Alexis Llewellyn), are as stunned as Audrey but, being kids, seem to have it in them to cope better and recover faster.

Jerry, caught up in a long downswirl and living in a flop house, had been Brian’s best friend since childhood. He’s dazed and out of it when told of Brian’s death, and has to be driven to the funeral reception. Audrey resented him when Brian was alive — she saw him as pure deadweight –but she feels lost and zombified in the days and weeks after the funeral, and one day she invites Jerry to live with her and the kids in a room attached to, but not part of, the house. Not as a mercy or pity gesture (although it’s partly that), but because she feels on some level that she needs some remnant of Brian to keep on with, or at least be near to.

So she helps Jerry out, and then he helps her out (particularly with the kids), and then things suddenly go wrong due to some moments of near-panic on Audrey’s part, which triggers the same in Jerry and before you know it it’s recovery time again and the slow, always difficult process.

Bier and screenwriter Allan Loeb stay as far away as you can imagine from the standard beats and turns in stories like these, first and foremost being the avoid- ance of romantic entanglement (although this is flirted with briefly). The sense of restraint and searching for “a different way to milk it” in Things We Lost in the Fire is constant and, in its own way, quite soothing. Delightful, in fact.

Cheers to a superb supporting cast, particularly John Carroll Lynch (as a next- door neighbor going through his own strife and uncertainty), Alison Lohman and Omar Benson Miller.

Things We Lost in the Fire producer Sam Mendes (l.), director Susanne Bier (r.)

Sam Mendes, director of American Beauty, Road to Perdition and Jarhead, is one of the producers. I don’t know what he specifically did to help make it turn out this well, but whatever it was, good for him. (Maybe he just got Bier hired, and then sat around and drank Starbucks coffee on the set.) In fact, hooray for everyone and anyone who had anything to do with the making of this film.

I can’t guarantee that N.Y. Times critic Manohla Dargis will dislike this film, and that her kinder, gentler colleague A.O. Scott will review it and say complimentary things, but I suspect this may be the case. A little voice is telling me this.