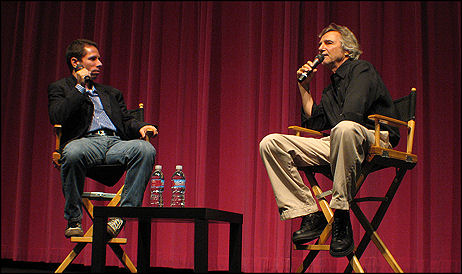

Director Curtis Hanson hosted an L.A. Film Festival screening last night at the Armand Hammer Museum’s Billy Wilder theatre of John Ford‘s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. I slipped into the theatre right after the exploitation films panel around 8:30 and caught the last 25 or 30 minutes, and then I sat through the post-screening discussion between Hanson and L.A. Weekly critic Scott Foundas. Variety critic Robert Koehler was also in attendance.

The scratch-free 35mm print was from John Wayne‘s private collection, Hanson said. It looked great, although it didn’t seem to have that super-silvery sheen and needle-sharp focus that I’ve gotten off viewings of the Paramount Home Video DVD.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance was critically dismissed for the most part when it opened in April 1962. N.Y. Times critic Bosley Crowther called it “creaky” and declared it proof that “the western, ravaged by repetition and television, has begun to show signs of age…[a] basically honest, rugged and mature saga has been sapped of a great deal of effect by an obvious, overlong and garrulous anticlimax.”

It didn’t make very much money either, and the reasons weren’t hard to figure. Ford shot Valance in black and white, and most of it on a somewhat echo-y sound stage. It’s very talky for a western. James Stewart and John Wayne are both 20 years too old to be playing their parts. And it’s basically an old man’s movie — an elegy for bygone times and regrettably false legends.

But elite critics starting calling it an absolute classic about 30 years ago. Transformers fans will never, ever rent the DVD, but every serious film critic from Maine to San Diego will tell you it’s one of Ford’s very best — his saddest and most personal film ever, and worthy of the highest respect.

I don’t dispute this for a second. You can talk about this film for hours and never run out of new things to discover or re-review. I’ve seen Liberty Valance many, many times on the tube, and I absolutely love the transfer on the most recent DVD.

But the older I’ve gotten (and I’ve said this before), the more trouble I’ve had with Ford’s sentimental cornball streak. The man’s affection for actorly colorfulness among his supporting players seems to get worse every time I re-watch one of his films. Andy Devine‘s performance in Liberty Valance as a cowardly, squealy- voiced sheriff is, for me, 90% torture. (His one good scene is in the very beginning when he takes Vera Miles out to visit Wayne’s burned-down ranch.) Edmond O’Brien‘s alcoholic newspaper editor is a problem performance also. The movie is littered with them.

As Newsweek critic Malcom Jones observed in March 2006, Ford’s movies “are a little antique, a little prim.”

The irony, of course, is that despite the irritating aspects, The Man Who Shot LIberty Valance becomes a greater and greater film with each re-viewing. Some- thing majestic and touching and compassionate seems to come out in greater and greater relief. Genius-level films always gain over the years, but to my surprise I was almost moved to tears last night — and this stagey monochrome oater has never quite melted me before. Go figure.