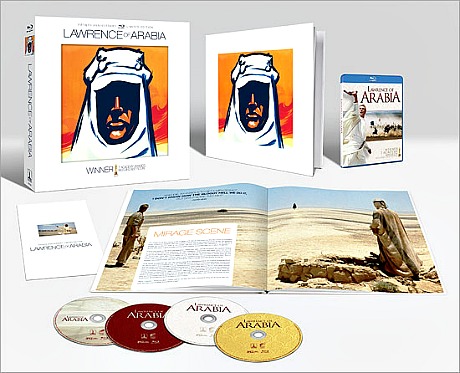

An L.A. Times story posted late last night (7.17) by Susan King discusses the long-expected debut of Sony Home Video’s Lawrence of Arabia Bluray (streeting on 11.13) as well as Thursday night’s AMPAS screening of a 4K digital version.

But the end of King’s story leaves a somewhat inaccurate impression.

“Over the years, the film was cut from its original length — a 187-minute version was released in the early 1970s to get more showing,” she writes. “But in 1989, a restored ‘director’s cut’ done by Robert A. Harris and Jim Painten under Lean’s supervision was released.” This is correct.

King then writes that Thursday night’s Academy screening “marks the U.S. premiere of the new digital restoration of the film — correct — “which used the original 65-millimeter negative.” Technically correct but a tad misleading.

Grover Crisp, executive vp, asset management, film restoration and digital mastering, tells King that “the original negative itself was actually quite scratched and not in good shape.” But with digital restoration, “the original negative is kind of the Holy Grail in this kind of work because the detail and sharpness were there in the negative so we wanted to work with that.”

This last graph suggests that Crisp went all the way back to the original 1962 negative and in so doing bypassed the elements created by Harris and Painten for the 1989 restored cut. Which isn’t true. A significant portion of Harris and Painten’s work used the original 1962 negative, and Crisp did go back to that for extra clarity’s sake, but several additions, refinements and enhancements that turned up in the 1989 Harris-Painten version were also included in Crisp’s final digital version, which was actually scanned at 8K.

Update: Harris has told me that what Crisp scanned was precisely what Harris created in 1988. He adds the following: “It would have been far easier for Crisp to simply take one of our 65mm interpositives and scan that, but he decided that what was best for the film was to scan our neg, which was in very worn condition. With this Crisp knowingly opened a Pandora’s Box, but for the betterment of the film. He’s been working with those elements tirelessly for two years, and went far beyond what any studio executive would normally have done. My hat is off.”