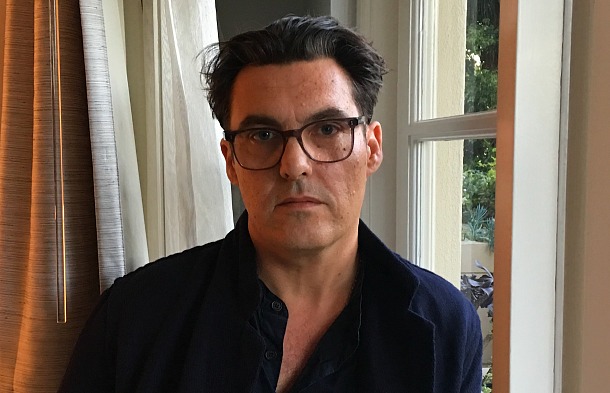

You have to play it carefully when you talk with Joe Wright, the 45 year-old director of Darkest Hour. You want to be respectful, of course, but you don’t want say the wrong thing. Because for seven-plus years (’05 through ’12) Wright was a knockout, high-style director with all kinds of exciting, mad-thrust energy, and then, all of sudden, he seemed to lose his vision or his footing or you-tell-me.

So you don’t want to ask him, “Uhm, have you gotten that magic-crazy thing back, or are you still recalculating and figuring out the next move?” Because that would sound insulting.

You can’t say what a audacious, flirting-with-genius talent he seemed to be during that seven-year period when he made Pride and Prejudice (’05), Atonement (’07), Hanna (’11) and the drop-to-your-knees Anna Karenina, which I found brilliant and dazzling and everything in between. Because telling him how great he seemed during this period would sound like an allusion to the disappointment his fans felt when he made Pan (’15), a costly, poorly-reviewed kids fantasy flick that lost money.

It follows that you wouldn’t want to ask him, as I did during a quickie interview two or three weeks ago, why he made Pan in the first place. Because he’ll just say, “Well, let’s just that one go.”

And you can’t express a hope that he’ll make another high-style work of genius in the vein of Anna Karenina because that would sound like “so what’s happened to you since Anna Karenina?”

And if you’re the last on a long list you can’t suggest doing a video interview because he’ll probably say, “I’m a little tired…I don’t know.” Okay, forget it.

What I said to Joe, whom I regard as a very important director in the realm of James Cameron and David Fincher, was that he obviously “shot the hell” out of Darkest Hour. But that wound up sounding as if “shooting the hell out of it” was Wright’s way of compensating for a relatively rote, somewhat conventional biopic, which Darkest Hour is to a certain extent. And that’s fine. It is what it is.

Darkest Hour reminds us that would-be tyrants like Adolf Hitler are still around, and that we could all use more fellows with the steel backbone of a Winston Churchill to stand up to them and inspire the old fighting spirit.

I admired and enjoyed Darkest Hour, and I respect the visual energy that Wright used to punch it up as best he could. But I still want the old Wright back. I can’t help myself. I’m fine with Darkest Hour, but I want a return of Joe, the gifted madman.

Here’s a portion of first review of Anna Karenina, which I posted on 9.6.12:

“Joe Wright‘s Anna Karenina (Focus Features, 11.16.12) will have its detractors (in my screening today five or six people were actually chuckling at it during a high-emotion scene in the late second act) but for me it’s a serious, drop-your-socks knockout — the first truly breathtaking high-style film of the year, a non-musical successor to Moulin Rouge and a disciple of the great ’70s films of Ken Russell (and by that I mean pre-Mahler Russell, which means The Music Lovers and Women In Love) as well as Powell-Pressburger’s The Red Shoes.

“You either go with the proscenium-arch grandiosity of a film like Anna Karenina or you don’t (and I was just talking in the Bell Lightbox lobby with a critic who didn’t care for it) but if you ask me it has all the essential ingredients of a bold-as-brass Best Picture contender — an excitingly original approach, cliff-leaping audacity, complex choreography, the balls to go classic and crazy at the same time, a wild mixture of theatricality and romantic realism, a superbly tight and expressive script by Tom Stoppard and wowser operatic acting with a special hat-tip to Keira Knightley as Anna — a Best Actress performance if I’ve ever seen one.

“The brazen idea behind Wright’s film is that he’s presenting a completely theatrical environment, and therefore defined by and subject to the terms of live theatre. The film literally takes place in a 19th Century theatre with the orchestra seats removed, and yet it’s a special kind of theatre that dissolves and opens up from time to time — regularly, literally — and thus allowing Wright and his players to run out or zoom into a semi-naturalistic world.

“But one is mostly aware that we’re watching a play that is choreographed like a musical or a ballet with broad but delicious acting and some magnificent dance sequences and killer production design and break-open walls and actors sometimes freezing in their tracks and becoming tableau.

“I can imagine some people saying ‘whoa…this is too much’ but like I said, either you understand the concept and accept it…or you don’t. I loved every minute of it except for a portion in the third act when it seems to run out of gas. But it revs up again at the finale.”