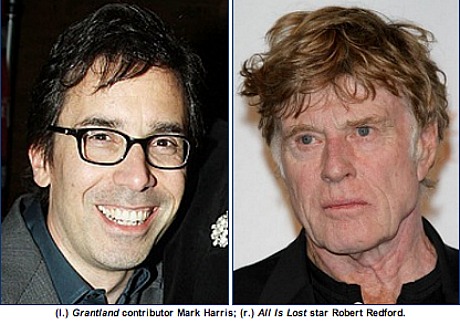

In his latest Grantland column, Mark Harris has advanced an idea about presumed Oscar-worthy performances that I’d kind of forgotten about or never really waded into. Academy members vote for an actor whom they admire for the skill and depth of his or her acting chops (as well as the degree to which they’ve physically disappeared into a character by losing or gaining weight or wearing a prosthetic nose) but also by the measure of how sorry they feel for the character he/she has portrayed.

Why do we feel sorry for a character or for anyone in real life? Because we’ve been there and we can relate. We know what it’s like to be in his or her shoes and what the shoulder weight feels like. Obviously Academy members vote for actors they like or admire or feel in awe of, but more often than not the deep-down thing kicks in and they vote for characters they feel closest to. Which is why, I’m suspecting more and more, All Is Lost‘s Robert Redford is probably going to win for Best Actor.

Because of the gold-watch factor, to some extent, and because he’s well-liked and respected and is, for a fairly large portion of the Academy membership, “Our Man.” But also because those who’ve thought for more than ten seconds about All Is Lost know that it’s about more than just a tough and intelligent old guy trying to survive on the high seas.

The real subject is about what it feels like for an older person trying to cope with nature’s constant mettle-testing adversity. It’s about the last phase for every human being who has ever made it to advanced years, and what this feels like on on all kinds of levels. All Is Lost says again and again (and this is the heartening element) that when the going gets tough your best friends (especially if you’ve made their acquaintance earlier in life) are focus, concentration, resourcefulness and tenacity. It also says that nature has no compassion and is in fact relentless and quite cruel. But that’s nature for you. One way or another it’s going to get you in the end.

I therefore suspect that Academy blue-hairs (which constitute a good portion of the membership) will relate to and feel more “sorry” for Redford than for 12 Years A Slave‘s Chiwetel Ejiofor, good and monumental as he obviously is in that role.

“Voting by which affliction Academy members feel saddest about would be a silly way to decide the prize,” Harris states. “But if that’s the way it’s going to go, start engraving Ejiofor’s name, because” — I love this part — “being a slave when you’re a free man is worse than getting AIDS in 1986 when you’re a straight guy” –i.e., Matthew McConaughey in Dallas Buyer’s Club — “which is worse than being stranded at sea and facing a watery grave when it’s really kind of your own fault” — Redford — “which is worse than getting your cargo ship hijacked” — Tom Hanks in Captain Phillips — “which is worse (or maybe not!) than serving as a butler and putting up with racism” — Forrest Whitaker in The Butler — all of which is way, way worse than merely being Bruce Dern in Nebraska.”

The fact that Harris doesn’t even allude to the All Is Lost metaphor shows once again that he’s shut down to its merits. (He didn’t even mention it as a faint Best Picture possibility on a recent Gold Derby projection.) Some might argue that Redford doesn’t really “act” in All Is Lost, but he does, of course — fear and anxiety seep out of him in just about every scene. And when you mix Redford’s performance with what the film is really about….well, c’mon. Not that Harris is inclined to notice.

He’s correct when he calls the early Redford Updike-like compared to the Roth, Bellow and Mailer-like performances that Robert De Niro, Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino were giving in their ’60s and ’70s heyday. Redford “often stood sheepishly apart from whomever he was playing, as if to say, ‘You and I both know who I am — why bother pretending anything else is going on?'” That’s true — he did exactly that. But that’s what all movie stars do to some degree. And yet during his role-of-a lifetime performance, audiences, says Harris, are contemplating Redford’s “dry-eyed, stony, weather-beaten-to-a-pulp countenance, searching for any signal from his emotional interior that might seep through the cracks and crevices.” Watching All Is Lost, he says, “is like having a ringside seat at a fight between Mount Rushmore and God. It’s a tour de force of withholding.”

Either you get it or you don’t, Mark. Arguing is futile.