M*A*S*H (’70) is easily the coolest, funniest and most financially successful Robert Altman film ever made, not to mention the inspiration for a hugely successful TV series that ran for 11 years. I therefore found it surprising, at first, that out of 20 Altman films The Guardian‘s Ryan Gilbey had ranked M*A*S*H in 19th place. My actual reactions were “how…why…what the fuck?”

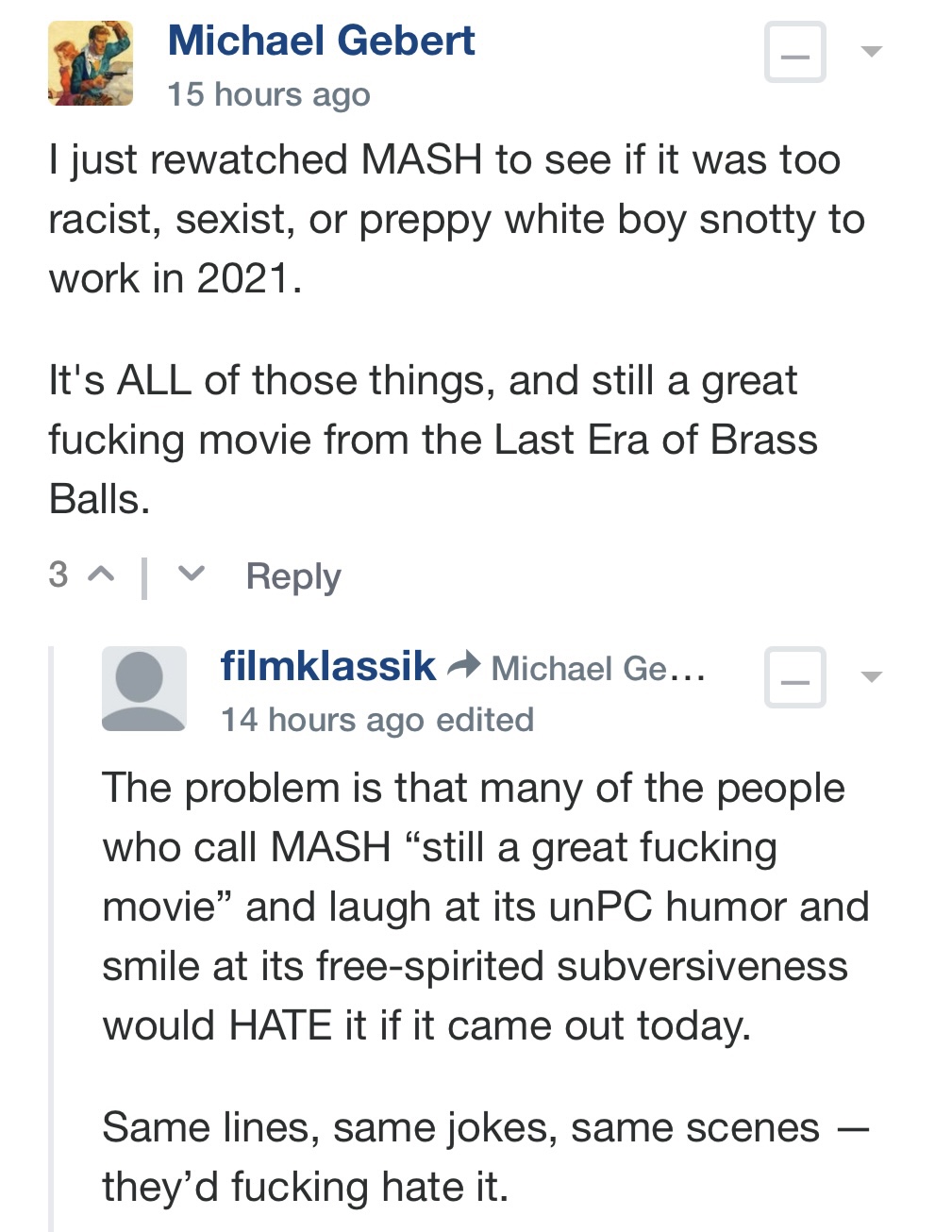

Then it hit me: Gilbey is on the youngish side, presumably born in the early to mid ’80s, and probably receptive to this or that wokester concern. (Three years ago Gilbey wrote that “it is difficult to see how the unquestioning reverence of directors can continue in this new climate of hyperawareness, where the constant drip-feed of discrediting stories proves once and for all that time’s up” — i.e., fuck Polanski, Allen and Bertolucci.) This led to a suspicion that Gilbey had probably downgraded M*A*S*H because of the cruel and abrasive way that Sally Kellerman’s uptight “Hot Lips Houlihan” is treated by M*A*S*H‘s Elliott Gould, Donald Sutherland, Tom Skerrit and the rest of the gang.

In short, this celebrated 1970 film has apparently fallen afoul of the #MeToo brigade and its allies.

I’m presuming that the outdoor shower humiliation sequence is regarded as particularly egregious. But the basic idea behind giving “Hot Lips” a hard time (along with her uptight boyfriend, Major Frank Burns, played by Robert Duvall) is that she’s an officious prig and “a regular Amy clown,” as Sutherland calls her in one scene.

“Hot Lips” (her actual name is Margaret) isn’t humiliated because she’s a woman or because Gould, Sutherland and the rest enjoy humiliating their betters or anything in that vein — she’s punished for being a rigid bureaucratic asshole — an officer more concerned with protocol and appearances than with behaving like a human being and somehow weathering the horrors of war, bloodshed and daily death. She walks around with a high regard for military tradition, and with a broomstick up her butt.

Roger Ebert, 51 years ago: “If the surgeons didn’t have to face the daily list of maimed and mutilated bodies, none of the rest of their lives would make any sense. When they are matter-of-factly cruel to ‘Hot Lips’ Hoolihan, we cannot quite separate that from the matter-of-fact way they’ve got to put wounded bodies back together again. ‘Hot Lips,’ who is all Army professionalism and objectivity, is less human because the suffering doesn’t reach her.”

In her 1.24.70 New Yorker review, Pauline Kael described “Hot Lips” as “a pompous fool.”

Kael also called M*A*S*H “the best American war comedy since sound came in, and the sanest American movie of recent years.” Pretty much everyone was in agreement back then.

M*A*S*H was set in 1951 Korea but was obviously played by actors rooted in the late ’60s. Gould and Sutherland’s hairstyles alone would never be tolerated in any 20th Century American military culture, and one of the first overheard lines (spoken by a M*A*S*H nurse) is that something-or-other is “a real drag.”

The mood of M*A*S*H was a revelation and a soother, and 1970 audiences fell head-over-heels. These irreverent surgeons were “hip Galahads,” as Kael put it, and “always on the side of decency and sanity.” Did they behave in a somewhat sexist manner, according to the standards of 2021? Yeah, but they weren’t jerks or dumb hounds — what mattered to them was getting through the Korean War their own way, and sometimes that included having it off with a willing nurse or downing of one or two martinis with fresh olives. Being smart fellows, they were simply accustomed to outsmarting the fools.

Ryan Gilbey is obviously not obliged to agree with Ebert, Kael and the multitudes who went wild over M*A*S*H back in the day, and he’s perfectly entitled to dismiss it because of behavior that doesn’t seem to pass muster by #MeToo standards. But posting this opinion makes him seem a little stiff-necked.

Most of Pauline Kael’s review:

“M*A*S*H is a marvellously unstable comedy — a tough, funny, and sophisticated burlesque of military attitudes that is at the same time a tale of chivalry. It’s a sick joke, but it’s also generous and romantic – an erratic episodic film, full of the pleasures of the unexpected. I think it’s the closest an American movie has come to the kind of constantly surprising mixture in Shoot the Piano Player, though M*A*S*H moves so fast that it’s over before you have time to think of comparisons. While it’s going on, you’re busy listening to some of the best overlapping comic dialogue ever recorded. The picture has so much spirit that you keep laughing – and without discomfort, because all the targets” — including “Hoi Lips” — “should be laughed at.

“The laughter is at the horror and absurdities of war, and, specifically, at people who flourish in the military bureaucracy. The title letters stand for Mobile Army Surgical Hospital; the heroes, played by Donald Sutherland and Elliot Gould, are combat surgeons patching up casualties a few miles from the front during the Korean war. They do their surgery in style, with humor; they’re hip Galahads, saving lives while ragging the military bureaucracy. They are so quick to react to bull — and in startling and unpredictable ways — that the comedy is, at times, almost a poetic fantasy. There’s a surreal innocence about the movie; though the setting makes it seem a ‘black’ comedy, it’s a cheery ‘black’ comedy. The heroes win at everything. It’s a modern kid’s dream of glory: Holden Caulifield would, I think, approve of them. They’re great surgeons, athletes, dashing men of the world, sexy, full of noblesse oblige, but ruthless to those with pretensions and lethal to hypocrites. They’re so good at what they do that even the military brass admires them. They’re winners in the war with the Army.

“War comedies in the past have usually been about the little guys who foul things up and become heroes by accident (Chaplin in Shoulder Arms, Danny Kaye in Up in Arms). In that comedy tradition, the sad sack recruit is too stupid to comprehend military ritual. These heroes are too smart to put up with it. Sutherland and Gould are more like an updated version of Edmund Lowe‘s and Victor McLaglen‘s Sergeant Quirt and Captain Flagg from What Price Glory and The Cockeyed World — movies in which the heroes retain their personal style and their camaraderie in the midst of blood and muck and the general insanity of war.

“One knows that though what goes on at this [Korean War] surgical station seems utterly crazy, it’s only a small distortion of actual wartime situations. The pretty little helicopters delivering the bloody casualties are a surreal image, all right, but part of the authentic surrealism of modern warfare. The joke the surgeons make about their butchershop work are a form of plain talk. The movie isn’t naive, but it isn’t nihilistic, either. The surgery room looks insane and is presented as insane, but as the insanity in which we must preserve the values of sanity and function as sane men.

“An incompetent doctor is treated as a foul object; competence is one of the values the movie respects — even when it is demonstrated by a nurse (Sally Kellerman) who is a pompous fool. The heroes are always on the side of decency and sanity — that’s why they’re contemptous of the bureaucracy. They are heroes because they’re competent and sane and gallant, and in this insane situatiion their gallantry takes the form of scabrous comedy. The Quirt and Flagg films were considered highly profane in their day, and I am happy to say that M*A*S*H, taking full advantage of the new permissive rating system, is blessedly profane. I’ve rarely heard four-letter words used so exquisitely well in a movie, used with such efficacy and glee. I salute M*A*S*H for its contribution to the art of talking dirty.

“The profanity, which is an extension of adolescent humor, is central to the idea of the movie. The silliness of adolescents – compulsively making jokes, seeing the ridiculous in everything – is what makes sanity possible here. The doctor who rejects adolescent behavior flips out. Adolescent pride in skills and games – in mixing a Martini or in devising a fishing lure or in golfing – keeps the men from becoming maniacs. Sutherland and Gould, and Tom Skerritt, as a third surgeon, and a lot of freakishly talented new-to-movies actors are relaxed and loose in their roles. Their style of acting underscores the point of the picture, which is that people who aren’t hung up with pretensions, people who are loose and profane and have some empathy — people who can joke about anything — can function, and maybe even do something useful, in what may appear to be insane circumstances.

“All this may sound more like a testimonial than a review, but I don’t know when I’ve had such a good time at a movie. Many of the best recent American movies leave you feeling that there’s nothing to do but get stoned and die, that that’s your proper fate as an American. This movie heals a breach in American movies; it’s hip but it isn’t hopeless. A surgical hospital where the doctors’ hands are lost in chests and guts is certainly an unlikely subject for a comedy, but I think M*A*S*H is the best American war comedy since sound came in, and the sanest American movie of recent years.”