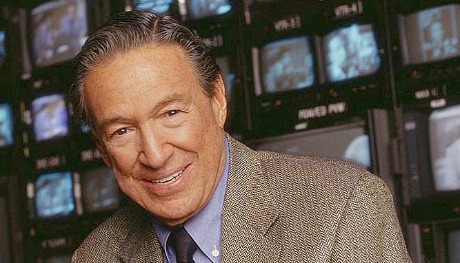

The legendary 60 Minutes interrogator Mike Wallace has died. A month shy of his 94th birthday, Wallace slipped into the after-realm “at a care facility in New Haven, where he had lived in recent years,” according to Tim Weiner‘s N.Y. Times obit. I flinched when I read that. The fearless Mike Wallace in an assisted living or medical care facility! What a ghastly, loathsome concept.

I talked to Wallace and his wife Mary a little more than five years ago at a Peggy Siegal party at MOMA. He was the youngest and healthiest looking and most intellectually alert 88 year-old I’d ever spoken to, and probably will ever speak to.

What did I say to Wallace? That being played by Christopher Plummer in Michael Mann‘s The Insider was one of the luckiest, most positive, image-enhancing things that could have happened to him. He’s portrayed as a charismatic guy who was flinty, tough and powerful, and then (a) made a mistake by kowtowing to CBS lawyers and corporate interests, (b) offered a memorable rationalization (“I don’t plan to spend the end of my days wandering in the wilderness of National Public Radio!”), (c) recognized his mistake, (d) revealed his remorse and feelings of vulnerability to Al Pacino‘s Lowell Bergman, (e) tore Gina Gershon‘s attorney character a new one (“What are you gonna do now? You gonna finesse me? Lawyer me some more? I’ve been in this profession fifty fucking years! You and the people you work for are destroying the most-respected, the highest-rated, the most-profitable show on this network!) and (f) set things right.

Plummer-as-Wallace had one other great line: “Fame has a half-life of 15 minutes. Infamy lasts a bit longer.”

I also asked Wallace what his regimen was — what he ate and didn’t eat, how much exercise, how much sleep he got, how much walking, how much reading, writing, TV time, online time…the whole rundown. Because I want to look as good when I get older. It was mostly a bullshit question since good health and a vibrant appearance are almost entirely about genetics, but I was genuinely impressed.

This was a guy who used to smoke like a chimney and did cigarette advertisements for Phillip Morris and Parliament in the 1950s and early ’60s.

Wallace’s journalistic reputation was that of an engaging and tenacious prick, “the Terrible Torquemada of the TV Inquisition.” I love this passage in Weiner’s obit: “As he grilled his subjects, he said, he walked ‘a fine line between sadism and intellectual curiosity.’ His success often lay in the questions he hurled, not the answers he received. ‘Forgive me’ was a favorite Wallace phrase, the caress before the garrote. ‘As soon as you hear that,” he told The Times, “you realize the nasty question’s about to come.'”

Nine weeks ago Plummer told Pete Hammond during a Santa Barbara Film Festival chat that Wallace “was a cruel guy but a great TV newsman.”

Wallace didn’t really come into himself and begin to mine his Mike Wallace-ness until the mid to late ’50s, when he was pushing 40. His hottest career phase happened with 60 Minutes, of course, which began in 1968 when he was 50.

Wallace’s Wiki page says he “was hospitalized [in the early ’80s] with what was diagnosed as exhaustion. But his wife, Mary, forced him to go to a doctor, who diagnosed Wallace with clinical depression. He was prescribed an antidepressant and underwent psychotherapy. Out of a belief that it would be perceived as a weakness, Wallace kept his depression a secret until he revealed it in an interview with Bob Costas. In a later interview with colleague Morley Safer, he revealed he attempted suicide circa 1986.”

Wallace played himself interviewing Andy Griffith‘s Lonesome Rhodes in Elia Kazan‘s A Face In The Crowd (’57)

Here’s an interview he did with Kirk Douglas in 1957, when Douglas had just finished shooting Stanley Kubrick‘s Paths of Glory.

“If you want mind-blowing,” I wrote at the time, “consider this quote from Wallace’s introduction: ‘Just the day before our interview, Mr. Douglas had completed shooting on The Vikings for which he had grown his hair long and he hadn’t yet had the chance to see his barber.” In other words Wallace is not only mindful of the regimented, bordering-on-military approach to men’s hair styles in 1957, but feels a need to actually prepare the audience for the shock of seeing Douglas’s coif, which is maybe a tiny bit longer and fuller than an average haircut worn by a typical Man in a Gray Flannel Suit. Lockstep conformity was the rule among urban male professionals of the ’50s, but Wallace’s remark borders on the absurd.”