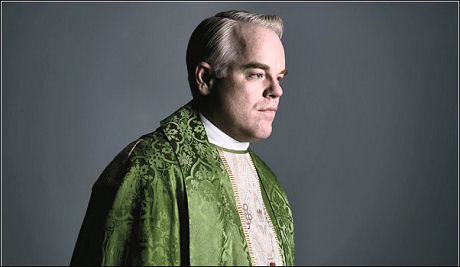

The character of Caden Cotard in Synecdoche “seems to echo many of Philip Seymour Hoffman‘s own internal debates and anxieties,” writes Lynn Hirschberg in her 12.21 N.Y. Times Sunday Magazine profile called “A Higher Calling.”

“I took Synecdoche on because I was turning 40, and I had two kids, and I was thinking about this stuff — death and loss — all the time,” Hoffman explains. “The workload was hard, but what made it really difficult was playing a character who is trying to incorporate the inevitable pull of death into his art. Somewhere, Philip Roth writes: ‘Old age isn’t a battle; old age is a massacre.’ And Charlie, like Roth, is quite aware of the fact that we’re all going to die.”

Yeah, and so what? This is why Synecdoche was a tank, despite the talent, brains and impressive chops of everyone concerned. We all know we’re dead meat. We all know the only way out is through the smokestacks. What matters is the luscious aroma of living, for Chrissake. And whether or not she’s inclined to slip you her phone number when her boyfriend isn’t looking.

“In 80 years,” Hoffman goes on, “no one I’m seeing now will be alive. Hopefully, the art will remain.” Yes, okay, hopefully. But I’m more with this Woody Allen remark: “I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work — I want to achieve it through not dying.”