If you couldn’t hit a note with a gun to your head, would you sing “Take Me Out To The Ball Game” in front of 50,000 people — as Denise Richards did yesterday at Wrigley Field? Singing this badly is a felony in most states. Ghastly.

Day: May 2, 2009

Celebs Eating Their Political Tails

Last night I attended a Tribeca Film Festival showing of Barry Levinson’s Poliwood, a blah-fine-whatever documentary about Levinson and his Creative Coalition pals attending numerous meet-and-greets at last year’s Democratic and Republican conventions, and then milling around at Barack Obama‘s inauguration last January. And it’s mainly….well, footage of this dedicated crew of actors (including Tim Daly, Anne Hathaway, Susan Sarandon, Ellen Burstyn, Alan Cumming, Josh Lucas, Matthew Modine, Richard Schiff and Rachael Leigh Cook) talking about how they’re looking to learn and contribute and how their fame doesn’t disqualify them from participating, etc.

All through the doc they discuss the fact that major issues and political news don’t seem to penetrate with the public without the aid of showbiz pizazz, famous faces, staged arguments and catchy graphics. Which is what the film is supposed to be about — i.e., the notion that politics has become entertainment, that television has blurred the lines between reality and myth, and that we’ve all lost our bearings as a result.

So Poliwood is a rhetorically earnest film, no question. But it pretty much ignores the irony that no one would be paying attention to these guys in the first place (or to Levinson’s film) if they weren’t famous Hollywood actors. So what’s this movie saying exactly that’s challenging and/or provocative? Nothing I can figure. It’s a muddle.

The only un-muddled thought in the entire film is when former MSNBC Tucker Carlson says that the idea of everyone in the nation learning about and participating in the political process is a myth. Most people probably shouldn’t participate, he says, because most of them out there are basing their beliefs on gut feelings and adversarial smoke and vague impressions fostered by blah-blah political talk shows, adversarial websites and other tangents of the breathless sound-byte media.

But there’s a genuine political process out there, Carlson says, and it’s something of an elite fraternity — a process that’s by the informed, of the informed and for the informed.

At last night’s Poliwood q & a at the BMCC theatre in lower Manhattan (l. to. r.): Barry Levinson, that amiable fat guy with the toupee who’s done focus-group testing for Fox News, Matthew Modine, Tim Daly and Josh Lucas

Precisely! And because I know for a cold fact that I’m one of the informed, I don’t feel confused or lost at all. The only one who seems confused, frankly, is Levinson, who can’t seem to get it clear in his own head that while the Creative Coalition team is a good-guy group trying to stand up for the right things, nobody cares very much about what Tim Daly or Ellen Burstyn have to say about this or that. I would probably agree with most of their views if we shared a sitdown, but that’s no reason for me to watch Poliwood. Or to recommend others to have a looksee.

Levinson recently summed up the movie’s point with a CNN interviewer, to wit: “I think what happened is, you have this television screen, and everything has to go through that screen — and at a certain point, I don’t think that we can tell the difference between the celebrity and the politician. They both have to entertain us in some fashion.

“That’s why I think, in second half of the 20th century, you saw this kind of change where John F. Kennedy was probably the first television politician. He came across, he was good-looking, he was great in the way he spoke, he had a certain sense of humor.

“Then you had [Ronald] Reagan. Someone looked at him giving a speech for [Barry] Goldwater and said, you know, he could be a politician. Two years after that, he became governor of California.

Tim Daly,Josh Lucas.

“So anyone [who] is pleasant enough on television suddenly gets credentials, whether they have earned it or not. And there’s that blurring of it between celebrity and politics and everything else.”

Accurate as Levinson’s observation is, I really don’t think it’s novel-enough or striking-enough to give weight and gravitas to this raggedy-assed home movie.

Evangelical Closet

Item #1: In Patrick Healy‘s 5.2 N.Y. Times piece about “Why Torture Is Wrong, and the People Who Love Them,” Christopher Durang calls his satirical play “a catharsis, a comic catharsis, for the last eight years. What’s particularly strange…is the play running when all of a sudden all these torture memos are released and discussed. It feels like I wrote some of these scenes yesterday.”

Item #2: A 4.30 CNN story reported that “the more often Americans go to church, the more likely they are to support the torture of suspected terrorists, according to a new survey. More than half of people who attend services at least once a week — 54 percent — said the use of torture against suspected terrorists is ‘often’ or ‘sometimes’ justified. The religious group most likely to say torture is never justified was Protestant denominations — such as Episcopalians, Lutherans and Presbyterians — categorized as ‘mainline’ Protestants, in contrast to evangelicals.”

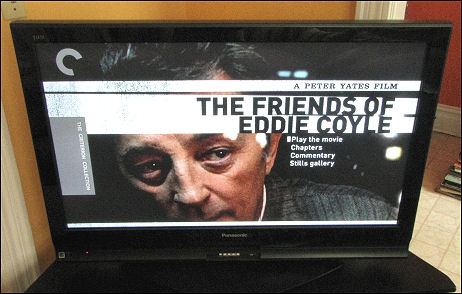

Coyle On The Shelf

I picked up the Criterion DVD of The Friends of Eddie Coyle yesterday. There’s a little booklet inside that contains a reprint of a superb Rolling Stone set-visit piece by Grover Lewis (a great journalist who died in ’95 of lung cancer) called “The Last Celluloid Desperado.” It also contains an eloquent essay by Kent Jones , the recently resigned Film Society of Lincoln Center director/programmer, called “They Were Expendable.”

In a discussion of Coyle costars Robert Mitchum, Peter Boyle, Richard Jordan Alex Rocco and Stephen Keats, Jones writes that “these actors, then in their prime, now signify a lost era. Many are dead — Mitchum in ’97, Boyle after a brilliant and successful career, the Harvard-educated Jordan far too early from a brain tumor, Keats by suicide before he turned 50. All of them worked hard on their craft and put flesh and muscle on an entire era’s worth of movies. With the notable exception of Boyle, few ever found roles as good as the ones they played in The Friends of Eddie Coyle.”

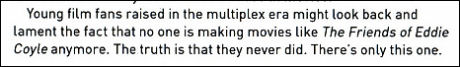

Here’s the closing paragraph in Jones’ essay:

And here’s a portion of the commentary by director Peter Yates that gives credit to former Paramount executive (and current Variety guy) Peter Bart for turning Yates on to the George V.Higgins‘ book and suggesting that a film be made of it.

And here’s some noisy dialogue that I’ve always loved, spoken by Keats.

The aspect ratio of Criterion’s Coyle is, of course, 1.85 to 1 or 16 x 9. It looks fine but was shot, of course, in Academy full frame (1.33 or 1.37 to 1) version. I have a full-frame version of Coyle sitting on my backup hard drive, and I have to say that I prefer this shape to the Criterion crop. I always prefer taller, boxier frames. The full-frame version of Dr. Strangelove , for example, is a more purely Kubrickian version than the 1.85 crop version.

Early scene from the 16 x9 Criterion Coyle

The boxier full-frame version of Coyle that’s sitting on my backup hard drive.

Odd Affinity

At some point in Douglas Brinkley‘s “Bob Dylan’s America,” a Rolling Stone cover story keyed to Dylan’s new album “Together Through Life,” is a passage about director John Ford. And I have to be honest and say that it bothers me somewhat.

cover of current Rolling Stone; director John Ford.

“At heart Dylan is an old-fashioned moralist like Shane, who believes in the basic lessons taught by McGuffey’s Readers and the power of a six-shooter. A cowboy-movie aficionado, Dylan considers director John Ford a great American artist. ‘I like his old films,’ Dylan says. ‘He was a man’s man, and he thought that way. He never had his guard down. Put courage and bravery, redemption and a peculiar mix of agony and ecstasy on the screen in a brilliant dramatic manner. [And] his movies were easy to understand.

“I like that period of time in American films. I think America has produced the greatest films ever. No other country has come close. The great movies that came out of America in the studio system, which a lot of people say is the slavery system, were heroic and visionary, and inspired people in a way that no other country has ever done. If film is the ultimate art form, then you’ll need to look no further than those films. Art has the ability to transform people’s lives, and they did just that.'”

Yes, of course — the director of The Grapes of Wrath, The Informer, How Green Was My Valley, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, The Horse Soldiers, Drums Along the Mohawk and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance was a superb visual composer and one of Hollywood’s most economical story-tellers bar none. His films were always layered and ripe with sub-currents that never flowed in one simple direction. His films always seemed fairly obvious and sentimental…at first. Then you’d watch them again and reconsider, and they always seemed to be about a lot more.

Except being a man’s man only goes so far. And I’m disturbed by Dylan being either oblivious to or deliberately overlooking the John Ford downside. The occasional staginess and jacked-up sentiment in just about every one of his films. The Irish clannishness, the tributes to boozy male camaraderie, the relentless balladeering over the opening credits of 90% of his films, the old-school chauvinism, the covert racism, the thinly sketched women, the “gallery of supporting players bristling with tedious eccentricity” (as critic David Thomson put it in his Biographical Dictionary of Film), and so on.

How could the guy who wrote “the ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face” not at least acknowledge the conflict between the majestic Ford and the whorish Irish sentimentalist? It’s depressing to consider a man who “once held mountains in the palm of [his] hand” being content to rely upon a distillation of a classic frontier ethos as the bedrock of his philosophy. I realize Dylan is a big Barack Obama fan, but it bothers me to think of him as a bit of a cultural conservative. Because Shane isn’t about old-fashioned morality, dammit. It’s nominally about a heroic, stand-up figure in buckskin, yes, but it’s really about a man grappling with — resisting — his basic nature only to finally give in to it at the end.