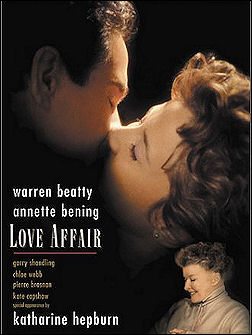

I’ve just finished reading 24 pages about the making of the embarassing Love Affair (1994) in Peter Biskind‘s “Star: How Warren Beatty Seduced America” (Simon & Schuster). Biskind offers quote after quote about how Beatty, the film’s star, producer and co-writer (with Robert Towne), marginalized and pretty much ignored and deballed Love Affair‘s director Glenn Gordon Caron.

Using quotes from several sources including Caron himself, Biskind also reports that director of photography Conrad Hall ignored Caron for the most part, treating him with little if any respect.

Towards the end of filming in late 1993 I was told similar stories by two excellent sources (the late production designer Richard Sylbert, a longtime Beatty collaborator and friend, and another insider I’d rather not name). And I included it in a file submitted to Entertainment Weekly‘s “News & Notes” section, edited at the time by Maggie Murphy, for a story about the making of Love Affair. The file made it clear that Beatty was really running the show and that Caron (hired off his rep as the creative light behind TV’s Moonlighting and Remington Steele) was the director in name only.

I talked to Beatty about these stories, not naming the sources but telling him I’d heard this and that, and he (a) denied that they were true and (b) calmly expressed outrage that EW was working on a story along these lines, which he naturally felt would tarnish the film as a troubled production and perhaps dent its box-office appeal. He mentioned at one point that he might sic his attorney, Bert Fields, on the magazine.

I don’t know who said what to whom, but I do know that EW decided to ignore the Caron-having-his-balls-cut-off angle when they ran their story a week or two later in mid-December 1993. Anne Thompson, who also did some Love Affair reporting, was assigned to write a cottonball piece called “Love and Warren” that said Beatty was a perfectionist and blah blah. It was basically a valentine.

The Caron angle was removed, I was told, because managing editor Jim Seymore didn’t like the fact that we couldn’t name the sources. I heard second hand that he told Murphy there was “no story here.” I always suspected this was code for “I’m feeling too much corporate heat on this thing so let’s kill it or water it down.”

I later told Beatty that by all appearances he’d played his cards well and had clearly won the round. If you have any sporting blood you have to respectfully acknowledge when you’ve been out-maneuvered.

I got pretty good at imitating Beatty’s voice. I remember calling Thompson during the end of the Love Affair episode. She picked up and said hello. “Anne Thompson?,” I said. Yes? “Warren Beatty.” She fell for it. “Hey-hey….howz it goin’?'” and so on. “Anne, Anne…I’m sorry. It’s Jeff. Foolin’ around…sorry. I wanted to see if I was good enough.”

Love Affair opened in October 1994 and was panned by just about everyone. I saw it once and found it flat and mundane. Roger Ebert was one of the few critics who gave it a break. It cost about $30 million and made $18 million, give or take. But Beatty would rebound four years later with Bulworth, one of the sharpest and most unflinching political comedies ever made in this country.