To hear it from N.Y. Times reporter Brooks Barnes, Vinny Bruzzese‘s Worldwide Motion Picture Group is either a proponent of the increasingly synthetic and cheese-whizzy nature of mainstream movies, or an outgrowth of this. Either way Bruzzese sounds to me like a slick and opportunistic type who would have gotten along just fine with Christopher Moltisanti while he was looking to refine and sell Cleaver.

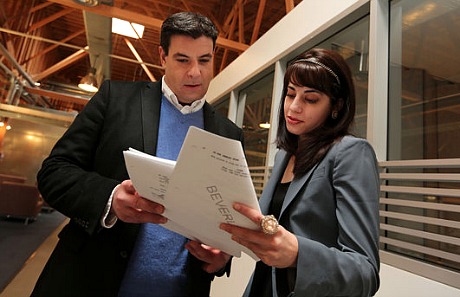

Worldwide Motion Picture Group honcho Vinny Bruzzese conferring with Miriam Brin, WMPG’s head of script analysis.

Bruzzese is apparently less of a calculating, self-created fiend than an inevitable manifestation of a development and production community that has less and less of a clue with each passing year. Either way he’s basically selling feelings of safety by advising production execs to favor cookie-cutter banality. Irving Thalberg would have taken one look and had the “gravelly-voiced” Vinny thrown right off the lot.

“For as much as $20,000 per script, Mr. Bruzzese and a team of analysts compare the story structure and genre of a draft script with those of released movies, looking for clues to box-office success.” WMPG “also digs into an extensive database of focus group results for similar films and surveys 1,500 potential moviegoers. What do you like? What should be changed?

“’Demons in horror movies can target people or be summoned,’ Mr. Bruzzese said. ‘If it’s a targeting demon, you are likely to have much higher opening-weekend sales than if it’s summoned. So get rid of that Ouija Board scene.’

“Bowling scenes tend to pop up in films that fizzle, Mr. Bruzzese, 39, continued. Therefore it is statistically unwise to include one in your script. ‘A cursed superhero never sells as well as a guardian superhero,” one like Superman who acts as a protector, he added.

“His recommendations, delivered in a 20- to 30-page report, might range from minor tightening to substantial rewrites: more people would relate to this character if she had a sympathetic sidekick, for instance.

“Script ‘doctors,” as Hollywood refers to writing consultants, have long worked quietly on movie assembly lines. But many top screenwriters — the kind who attain exalted status in the industry, even if they remain largely unknown to the multiplex masses — reject Mr. Bruzzese’s statistical intrusion into their craft.

“’This is my worst nightmare,’ said Ol Parker, a writer whose film credits include The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. ‘It’s the enemy of creativity, nothing more than an attempt to mimic that which has worked before. It can only result in an increasingly bland homogenization, a pell-mell rush for the middle of the road.”

“Mr. Parker drew a breath. ‘Look, I’d take a suggestion from my grandmother if I thought it would improve a film I was writing,’ he said. ‘But this feels like the studio would listen to my grandmother before me, and that is terrifying.’”