I didn’t post anything about Adam McKay‘s The Big Short because…well, because I feel I should give it another chance. So I’ll be buying and reading Michael Lewis’s book and re-seeing it again on Saturday. I got most of it, generally speaking. But I don’t have a place in my head for high-stakes betting, and I didn’t understand some of the fast-flying terminology. Some of it felt too dense and arcane and wonky, and I was (and still am) too dumb to fully process it. So I’ll be re-immersing tomorrow and maybe writing something on Sunday.

“Adam McKay‘s Big Short bid to leap from Anchorman director to Oscar contender is a bold one, but his let-me-spell-it-out-for-you comic take on the financial crisis still flew over the heads of many befuddled media members I spoke to.” — from 11.13 Oscar Futures post by Vulture‘s Kyle Buchanan, posted late this afternoon.

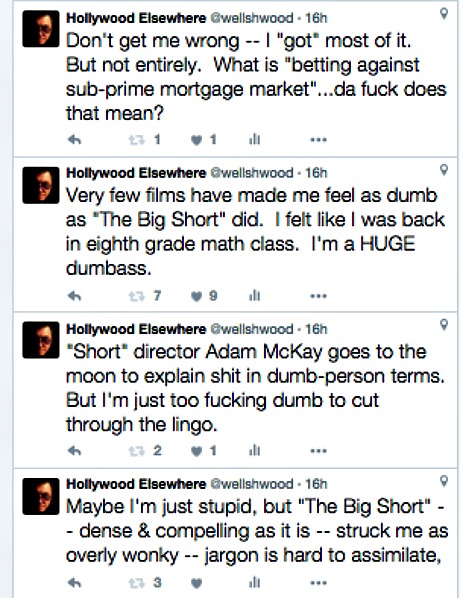

Me to 3 Guys Who Saw Big Short A While Back & Told Me How Game-Changing It Was: “You didn’t tell me it was really wonky…that a viewer has to contend with loads of impenetrable jargon, and that sometimes it’s hard to keep up with what is actually going on. Don’t get me wrong — I understood the basic shot and some of the specifics, but not all of it, and sometimes I was muttering to myself ‘…the fuck?’ Some of that terminology is hard to wrap around your head, bro.

“And you guys didn’t even mention this when I asked you for reactions? You didn’t bury the lede — you ignored it altogether. You mostly just said ‘very good’ and ‘Carell, Carell, Carell.’ What do you have to say for yourselves now that the truth is known far and wide?

“You glad-handed it. You sold me a bill of goods. You led me down the garden path. You pulled the wool over my eyes. You tied a tin can to my tail.”

Response from Tipster #1: “Jeff, you’re on some madness. There’s nothing in that movie that’s particularly hard to understand. It’s not a traditional film in the sense that it has a multi-plot structure and it isn’t necessarily narratively traditional, but the key scam seems clear: the banks forced the rating agencies to give bogus ratings to the loans that allowed them to sell them and pretend they were secure loans when in fact they were garbage likely to default.

“This is really all you need to understand, and it came through for me.

“A secondary point is that federal oversight at the SEC and other agencies was pathetic, and the government failed its citizens, in part because of the revolving door between government and the finance industry. Some smart guys figured out the game was soon to be up, bet heavy, and won. Carrell’s moral dilemma is somewhat contrived for dramatic effect, but I’d bet none of these guys felt exactly right about building their fortunes off other people’s misery – – unlike Goldman Sachs.”

Response from Tipster #2: “What can I tell you, Jeff? It made me feel a bit smarter. If I were you I wouldn’t proclaim how this movie left you in a dizzy haze. People at least have the perception that you’re on top of things, that you’re a smart guy. Don’t burst their bubble, Bubba.”

My Response to Tipster #2: “I’m not the only one crying ‘too dumb!'”