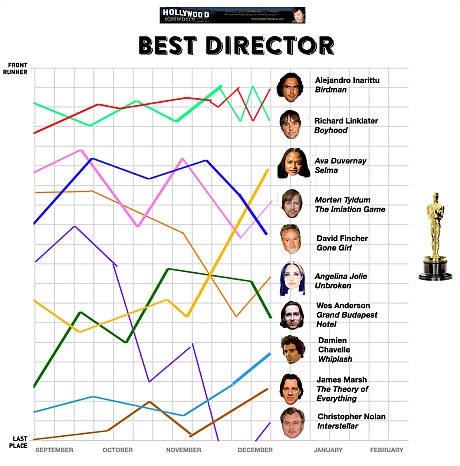

Two and a half days days ago The Washington Post‘s Karen Tumulty evaluated the accuracy of Selma‘s disparaging portrayal of President Lyndon Johnson, particularly its assertion that LBJ was initially reluctant if not hostile to supporting voting rights legislation (i.e., particularly during an argumentative meeting he had with Martin Luther King in December 1964). The film also clearly suggests that Johnson told FBI director J. Edgar Hoover to send audiotapes of MLK having it off with his motel girlfriends to wife Coretta Scott King. Tumulty’s piece, posted on 12.31, found the reluctant-to-support-legislation aspect highly disputable and the Hoover sex-tape flat-out wrong. King ally and confidante Andrew Young, in a three-way phone conversation with himself, Tumulty and Selma director Ava DuVernay, “lavished praise” on Selma but said its “depiction of the interaction between King and Johnson ‘was the only thing I would question in the movie…everything else, they got 100 percent right.’ (DuVernay declined to be interviewed on the record by Tumulty.) Tumulty also extracted an unequivocal denial from former Johnson special counsel Larry Temple about Johnson allegedly okaying the hassling of MLK with Hoover’s sex tapes. “I’m 100 percent sure that was not true,” Temple says. Another Selma fact-checking piece, posted today by Entertainment Weekly‘s Jeff Labrecque, concurs with Tumulty’s assessments in these two areas.

In a 1.2.15 follow-up article about the fact-checking “gotcha game”, Washington Post film critic Ann Hornaday (who contributed reporting to Tumulty’s piece) concludes with the following: “The correct question isn’t what Selma ‘gets wrong’ about Johnson or King or the civil rights movement, but whether we are sophisticated enough as viewers and thinkers to hold two ideas at once: that we’re not watching history, but a work of art that was inspired and animated by history. That we’re having an emotional and aesthetic experience, not a didactic one. That the literalistic critiques of historians and witnesses can co-exist — fractiously, but ultimately usefully — with the kind of inspiration, beauty and transformative power that the very best cinema such as Selma can provide.” Translation: Selma‘s slagging of LBJ isn’t such a bad thing because many of us found the film emotionally moving and that’s what counts in the end — mesmerizing art and passion transcends all. Particularly when the director is not only female but African-American, and in this context is currently making history on the awards circuit.