It is my earnest opinion that N.Y. Times critic Manohla Dargis used to be one of the very best in all respects. I’m a serious longtime fan, as I first began savoring her critiques when she wrote for the L.A. Weekly. And I still get the tingles when I re-read her N.Y. Times review (8.6.04) of Michael Mann‘s Collateral. But time passed, Trump came along, #MeToo was born, a domestic version of China’s Great Cultural Revolution of the ’60s kicked in, and Dargis turned woke.

I won’t present a chapter-and-verse dossier that shows exactly where Dargis seemed to turn the corner, but it was roughly around the time when the Times seemed to ease up on its commitment to redefining or re-enforcing its sterling Gray Lady reputation and instead became a woke activist newspaper committed to progressive change. The publishing of the 1619 Project, the resignation of James Bennet and Bari Weiss, the firing of Donald McNeil Jr. and so on.

I’m certainly no final arbiter, but to me and others, Dargis (along with co-critic A.O. Scott) seemed to increasingly side with the wokes.

Friendo: “Woke…yup. Her and Tony. And so we no longer trust them as critics. We don’t trust their lists, their reviews, etc.”

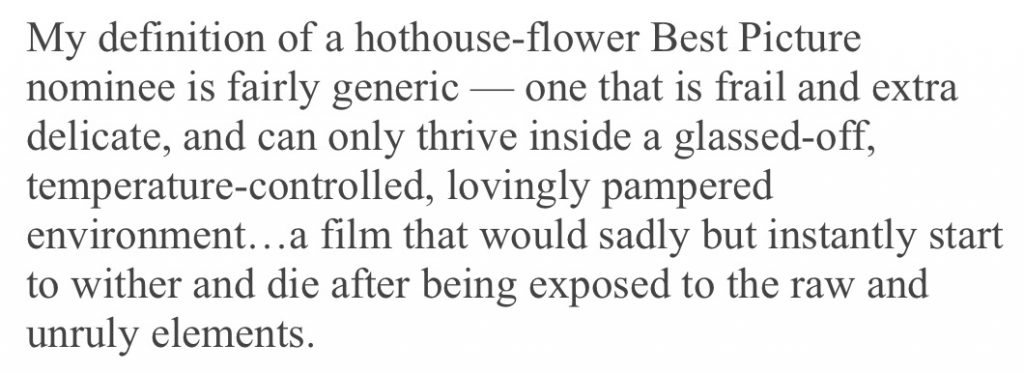

I’m mentioning this because eight days ago (1.26) the Times posted a long Dargis essay titled “For the First Time Ever, I’m Optimistic About Women in the Movie World.” It was basically a celebration of the increasing presence of women filmmakers…fine. 12 years ago “women comprised 7 percent of all directors working on the Top 250 films of 2009,” according to an annual report on women in film from researcher Martha M. Lauzen, and now, according to Lauzen’s 2022 study, “women accounted for 18 percent of directors working on the Top 250 films.”

Which is obviously encouraging, although that percentage could and should be higher, providing, I should add, that future women-directed films are at least partly in the region of Kathryn Bigelow‘s game-changing The Hurt Locker, say, and less in the camp of Sarah Polley‘s Women Talking.

But as I read the Dargis piece I began muttering to myself, ‘This is basically a pep-rally manifesto…an article that says “yay team, hooray for our side, we’re gaining in power and influence…representation!’

It felt less like an essay by a brilliant film critic whose primary allegiance was to the Universal Church of Cinema — something personal, soaring, nervy, revelatory, exacto-knifey — and more like an eloquent political pamphlet piece…a political speech that might have been delivered by Dargis at a recent Women in Film gathering, say, or submitted as a possible chapter in an anthology book about the growing community of brand-name women filmmakers.

Do film critics have to constantly criticize or take down or scold? No — it’s not only fine but necessary, most of us would agree, to celebrate what seems like positive or at least hopeful change in the film industry. Same deal if Andrew Sarris or Pauline Kael had written a 1969 Film Comment piece about the exciting new energy coming out of Hollywood since the smash success of Easy Rider, say. All to the good.

But Dargis’ cheerleader piece really didn’t feel like the Dargis of yore. It felt wokey-wokey and perhaps even Elmer Gantry-ish on a certain level. (Not in a hucksterish sense but with a certain fundamentalist revival-tent feeling.)

It almost seemed as if Dargis was saying in subtext, “I’m not just feeling good about the increasing power of women filmmakers, but also…I want to say this carefully…I’m also sensing a primal change within myself. I feel as if I’ve crossed over in a Malcolm X-meets-#MeToo sort of way…I used to be a disciple of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam, to to speak, but three of four years ago I began to gradually convert to the Sunni faith, and my spirit has led me in new directions.”

In other words, Dargis seemed to be saying “I used to be a ‘film critic but since 2019 or thereabouts — and I mean this in the manner of Thomas Becket‘s admission to Henry II by way of Jean Anouilh — I have become introduced to greater responsibilities.”

“Hauser vs. Dargis–Scott Eccentricity,” posted roughly a year ago.

Over the last three or four years Dargis and Scott’s critical judgments, to borrow a phrase from Scott’s 2001 Pearl Harbor review, have been “strenuously respectful of contemporary sensitivities.”

Many of the comments about Dargis’s piece were, as you might expect, strident: “Very confused why the N.Y. Times needs to take 2,500 words to tell me I should feel optimistic that ‘in 2022 women accounted for 18 percent of directors working at the top of their field.’ So 1/2 of the population getting to speak for 1/5 of the time gives us the healthiest and most dynamic picture of modern life and reflects a value system we don’t actively have to worry about, for now…forgive me for still being worried.”