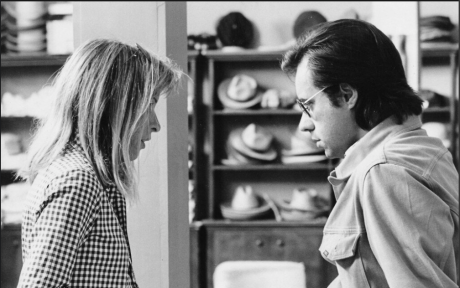

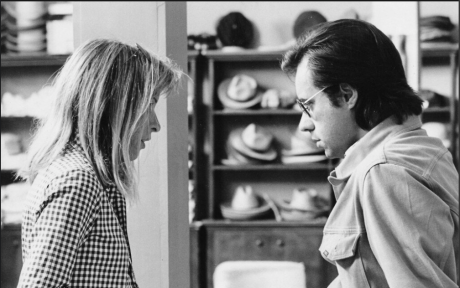

Ryan O’Neal‘s passing returned me to a nice ’90s friendship I had with the late producer Polly Platt, who was married to Peter Bogdanovich between the late 60s and early ’70s, and was a key creative contributor to PB’s Targets, The Last Picture Show, What’s Up Doc and Paper Moon. Talk about your glorious days of early ’70s cinema. Platt, Bogdanovich and O’Neal were joined at the hip for two or three years back then (along with several other hip industry hots). Now all three arw gazing down upon the planet, like Keir Dullea at the end of 2001.

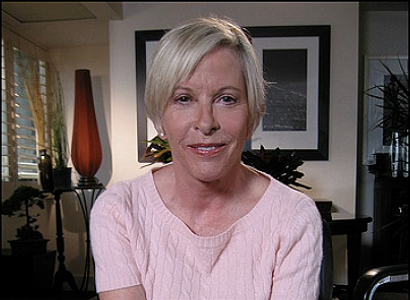

“Dearest Polly Platt,” posted on 7.27.11: “The death of Polly Platt from Lou Gehrig’s Disease (a truly horrible way to go) was announced today. I knew and liked Platt, and I’m truly sorry that’s she gone. She was a whip-sharp, very perceptive producer and production designer who flourished in the late ’60s, ’70s, ’80s and ’90s. In her prime she was a master at working this town. She knew everyone and everything. Her mind was incandescent. One of the sharpest, shrewdest and most nakedly honest X-factor creatives I’ve ever known.

I had a pretty good relationship with her in the ’90s when I wrote for Entertainment Weekly, People and the L.A. Times. She helped me with various “this is what really happened” stories from time to time, especially when she worked for James L. Brooks and produced I’ll Do Anything and Bottle Rocket.

She offered friendship, political support and wise counsel to Wes Anderson, Owen Wilson and Luke Wilson during the making of Bottle Rocket. The odd thing is that Platt told me she didn’t think that their movie, now regarded as a seminal ’90s film, had turned out all that well. She thought it should or could have been something else, I guess.

Platt started in the late ’60s as a production designer, and then segued into producing (and exec producing) in the mid ’80s with Broadcast News, Say Anything, The War of the Roses, the afore-mentioned I’ll Do Anything and Bottle Rocket, and The Evening Star. She did the production design on The Witches of Eastwick, Terms of Endearment, The Man with Two Brains, Young Doctors in Love, A Star Is Born (’76), The Bad News Bears, The Thief Who Came to Dinner, and four early movies with ex-husband Peter Bogdanovich — Targets, The Last Picture Show, What’s Up Doc and Paper Moon. She was Bogdanovich’s greatest creative counselor and political ally, Cybill Shepherd notwithstanding.

Honestly? I got a little pissed at Polly in ’94 when I FAXed her a letter about how she and Brooks and Columbia should consider releasing both cuts of I’ll Do Anything — the allegedly disastrous musical version that nobody ever saw plus the non-musical version that went into theatres. Platt showed that letter to Pat Kingsley, the tough, combative publicist who was repping Brooks (or the film) at the time. I was told that Kingsley took that letter to an Entertainment Weekly editor and said, “Look how Jeffrey Wells, who’s reporting on our film, is crossing lines by suggesting changes in our film…he’s not respecting journalistic boundaries.”

That was easily the most sickening move I’d ever suffered at the hands of an adversarial publicist. I wrote that letter out of passion for the musical form and respect for what Brooks had tried to do. And Kingsley tried to beat me with it, and Platt gave her the stick. I didn’t speak to Polly for about a year after that.

I sucked it in and made up with Polly a year later, and she helped a lot — a whole lot — with an L.A. Times Syndicate story that I wrote about Bottle Rocket in ’96.

Polly was a great lady to know and shoot the shit with. I’m sorry it ended for her after a mere 72 years.