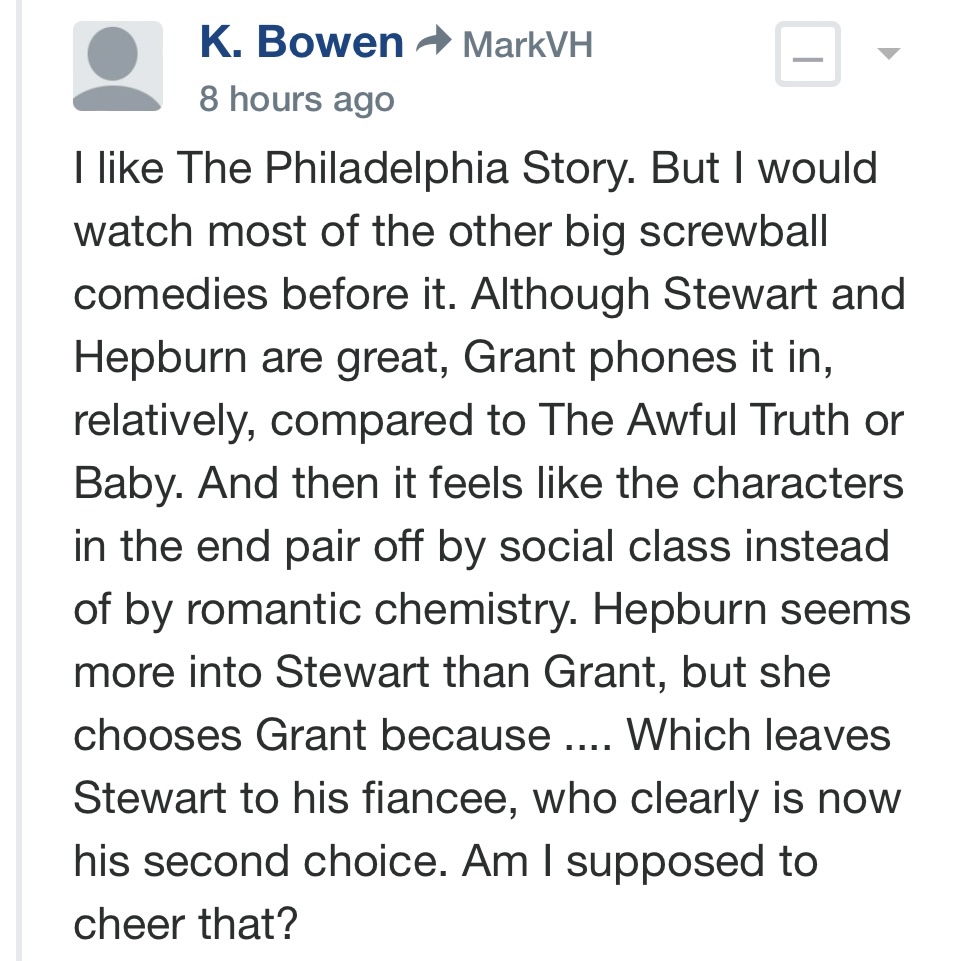

Last night HE commenter “K. Bowen” noted a key flaw in Phillip Barry’s well-liked The Philadelphia Story (a 1939 Broadway play, and then a 1940 film from director George Cukor), or more precisely in how the play’s romantic relationships are sorted out in the third act:

HE response: That’s completely accurate. Cary Grant and James Stewart’s characters DO pair off at the end with their social-class equals, and yes, Stewart is CLEARLY more attracted to Hepburn than Ruth Hussey, who genuinely loves him but for whom he feels no fire in the loins.

In the end Stewart offers to marry Hepburn, but is turned down because Hepburn is more profoundly drawn to ex-husband and social equal Grant. So Stewart somewhat meekly and dejectedly accepts a union with Hussey, his own social equal.

Original play author Phillip Barry & screenwriter Donald Ogden Stewart are basically saying “stick with your own kind” and “accept the social order of things” — wealthy blue-bloods belong with other wealthy blue-bloods, and middle-class strivers like Stewart’s Macaulay Connor and John Howard’s George Kittredge, a pretentious and moustachioed stuffed shirt if there ever was one, are better off with women of their own station.

So on one hand TPS is socially frank and realistic but on the other hand somehwat chilly and stifling. Compare this with the much nervier and more free-of-spirit, social-order-be-damned theme of Barry’s Holiday , which also costarred Hepburn and Grant.

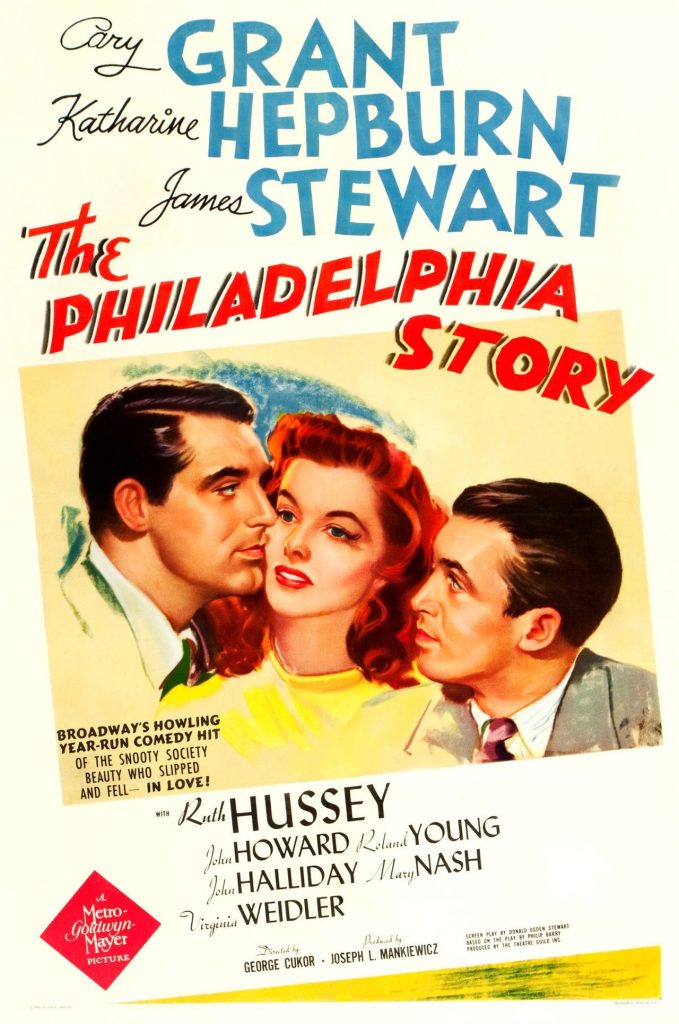

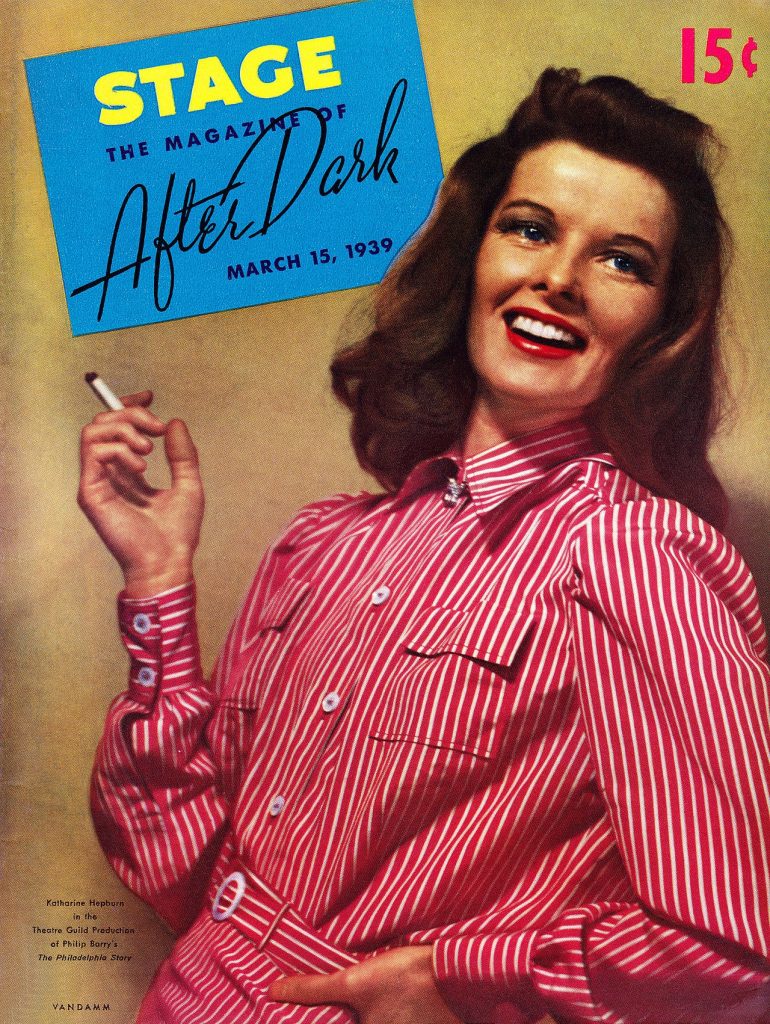

Note: Grant’s C.K. Dexter Haven uses a pet nickname for Hepburn’s Tracy Lord — “Red.” Hepburn’s hair color is front and center in the full-color poster, of course, but vague by way of Joseph Ruttenberg’s black-and-white cinematography. Hepburn’s freckly complexion (a typical red-hair component) was often obscured by makeup in her monochrome, big-studio heyday. Her natural red-auburn coloring was unmissable in John Huston’s richly hued The African Queen (‘51) and David Lean’s Summertime (‘55).