My 2.17 review of Roman Polanski‘s The Ghost Writer came out decently, I think, given the haste and the coffee-shop conditions that influenced the writing of it. But David Denby‘s appreciation in the 3.8.10 issue of the New Yorker is the most eloquent I’ve read anywhere. I’m posting this to remind how utterly wrong and short-sighted the Doubting Thomases have been on this film. History will judge them fairly — i.e., without mercy.

The only weird part of Denby’s review is a statement that The Ghost Writer is “the best thing Polanski has done since the seventies.” It’s actually the best thing he’s done since The Pianist.

Excerpt #1: “The Ghost Writer offers not the blood and terror of Polanski’s early work but the steady pleasures of high intelligence and unmatchable craftsmanship — bristling, hyper-articulate dialogue (the stabs are verbal, and they hurt) and a stunning over-all design that has been color-co√∂rdinated to the point of aesthetic mania. [It’s an] extraordinarily precise and well-made political thriller.”

Excerpt #2: “Polanski takes care that the…story is never rushed, mauled, or artificially heightened — the usual style of thrillers now. He respects physical plausibility and the passage of time; he wants our belief in his improbable tale, just as Hitchcock did. There may be nothing formally inventive in this kind of classical technique, but, in the hands of a master, it’s smooth and satisfying, and I suggest, dear reader, that you gaze upon it, because it’s all but gone in today’s moviemaking world. There’s not much violence in the movie, but your scalp tightens anyway.”

Excerpt #3: “[Polanski] concludes The Ghost Writer with a twin flourish: first, a virtuoso travelling shot of an explosive note slowly but inexorably passed through many hands at a social occasion until it reaches its destination, and then a final shot of Lang’s manuscript, the fluttering pages now forlornly scattered about a London street. As in the famous last sequence of Chinatown, Polanski is close to despair, but his rejuvenation as a film director is a sign of hope.”

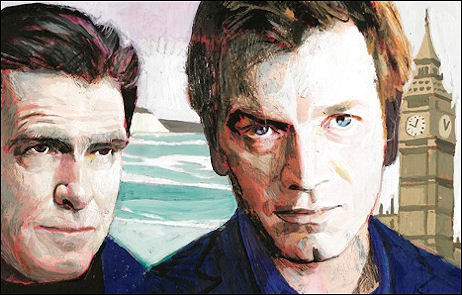

Excerpt #4: “Pierce Brosnan gives the strongest performance of his rather lazy career. He doesn’t imitate [former Prime Minister Tony] Blair; he offers his own interpretation of a public man’s impersonally brisk and hardened charm — the smile is reflexive, dazzling, and savage. Lang tells stories about his youth with hearty indifference to their phoniness — even in retreat, he’s a calculating pol, playing the angles, manipulating his eager amanuensis. And, when Lang is criticized or challenged in any way, Brosnan’s charm dissolves into fury; he catches the defensive self-righteousness of power, a leader’s disbelief that anyone might be seeing through him

Excerpt #5: “Olivia Williams is Ruth, Lang’s brilliant wife and longtime political adviser. Slender and tense, with short dark hair, Williams pulls her legs up under her chin as she sits . Williams’s gaze could sear the fat off a lamb shank, and her line delivery is withering, yet Ruth is badly wounded, and Williams makes her sympathetic — she’s one of the rare actresses who seem more intelligent and beautiful as they get angrier.”