In his review of Universal Home Video’s DVD of Henry Hathaway‘s Trail of the Lonesome Pine (out July 7th), DVD Beaver’s Gary W. Tooze says the digital mastering of this 73 year-old film “may be one of the best looking SD transfers I’ve ever seen of a film over 50 years old.

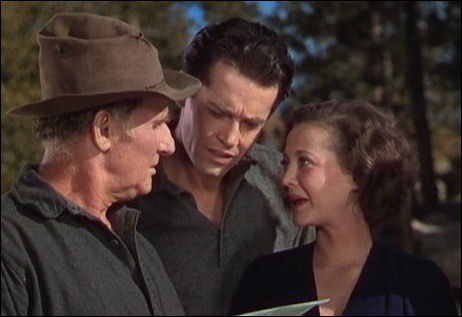

(l. to r.) Fred Stone Henry Fonda, Sylvia Sidney in Trail of the Lonesome Pine (1936)

“The colors look wonderful — no bleeding. Detail is shockingly strong. I didn’t see anything on the box about restoration. It can look a shade glossy but it’s also extremely clean with no untoward chroma or disturbing artifacts. I’m both utterly impressed and perplexed at how it can look this good. Wow!”

I love that N.Y. Times critic Frank Nugent devoted the first five paragraphs of his nine-graph review (dated 2.20.36) to Trail‘s groundreaking cinematography, being the first color feature to be shout outdoors.

“Color has traveled far since first it exploded on the screen last June in Becky Sharp,” Nugent began. “Demonstrating increased mastery of the new element, Walter Wanger‘s producing unit proves in The Trail of the Lonesome Pine, which opened yesterday at the Paramount, that Technicolor is not restricted to a studio’s stages, but can record quite handsomely the rich, natural coloring of the outside world and whatever dramatic action may be encountered in it.

“The significance of this achievement is not to be minimized. It means that color need not shackle the cinema, but may give it fuller expression. It means that we can doubt no longer the inevitability of the color film or scoff at those who believe that black-and-white photography is tottering on the brink of that limbo of forgotten things which already has swallowed the silent picture.

Fred McMurray, Sylvia Sidney

“Chromatically, Trail of the Lonesome Pine is far less impressive than its pioneer in the field. Becky Sharp employed color as a stylistic accentuation of dramatic effect. It sought to imprison the rainbow in a series of carefully planned canvases that were radiantly startling, visually magnificent, attuned carefully to the mood of the picture and to the changing tempo of its action.

“The new picture attempts none of this. Paradoxically, it improves the case for color by lessening its importance. It accepts the spectrum as a complementary attribute of the picture, not its raison d’etre.

“In place of the vivid reds and scarlets, the brilliant purples and dazzling greens and yellows of Becky, it employs sober browns and blacks and deep greens. It may not be natural color, but, at least, it is used more naturally. The eye, accustomed to the shadings of black and white, has less difficulty meeting the demands of the new element; the color is not a distraction, but an attraction–as valuable and little more obtrusive than the musical score.

“Lest this be interpreted as a completely eulogistic bulletin, let it be known that the Paramount’s new film is far from perfect, either as a photoplay or as an instrument for the use of the new three-component Technicolor process. Again speaking of the color, it would appear that blue still baffles the camera, that light browns have a tendency to run to green, that red is either extremely red or hopelessly orange. These are remediable defects, we feel, and ones that Hollywood’s skill will overcome.”