The first 60% of Chris Santana’s 2016 compilation reel feels superficial as fuck. Way too much emphasis on CG/animated “whoa!” moments. No attempt to suggest underlying currents or themes or meditations. No adult perspectives or side angles. Pure funhouse. Then it settles down during the last third. But not enough for me. Basically depressing. Thumbs down.

Jeffrey Wells

Jeffrey Wells

Have To Start Somewhere

It’s time to spitball what the Best Picture hotties will be twelve months hence.

Every January I begin to compile a list of likely or at least promising-sounding goodies. I thought I’d start a little earlier so that by New Year’s Day I’ll have a half-decent 2017 roster to build from. It’s always hard to cut through the smoke and try to figure out what might poke through. Right now I can’t see much out there. If you check the usual sites and sources (Wikipedia, Box-Office Mojo release schedule) it’s all the same old nauseating crap — the usual mind-melting, idiot-brand, animal-friendly superhero franchise CG Asian-market slop.

Theatrical films are slowly dying, certainly if you go by the product being cranked out by the five families these days, but never say die. Netflix, Amazon, Megan Ellison, A24, Scott Rudin, Sony Pictures Classics…anyone and anything that turns the key. Ambitious theatrical fare…what is that these days? Most believe the form can only go downhill, but the discipline of having to put it all together and cram it into 95 or 110 or 125 or 140 minutes (as opposed to the relative ease of sprawling Westworld-like longforms)…there’s something so vivid and extra-feeling when movies somehow manage to do that thing and deliver like it matters. I wouldn’t want to live in a realm in which people aren’t trying like hell to keep doing this, each and every year.

I’m looking to spitball a rundown of (a) the possible standouts at Sundance 2017, (b) at the Berlinale in February, (c) possible outliers from the winter, spring and even summer seasons that might go against the grain by being actually good, (c) potential Cannes headliners, (d) the Toronto, Venice, Telluride poppers, and (e) the Thanksgiving-Xmas films. No fucking franchises, no Marvels, no horror unless we’re talking Witch or Babadook-level, no monsters, no zombies, no end-of-the-world dystopia, no action-for-action’s-sake, no comic-book adaptations, no anime. And I don’t want to hear (much less think) about family-geared animation unless it’s some extra-level Pixar thing.

I’ve asked a few friends who usually hear about stuff, and now I’m asking the HE community. Any hints or clues of any kind would be appreciated. A couple of months hence I should have a list of 25 or 30 films that will at least start things off.

Lindsay Anderson’s If…

If I believed in Christian mythology, I would be greatly concerned right now about the very distinct possibility that Donald Trump is the Anti-Christ. I’m half concerned about this anyway, and I couldn’t be less invested in Christian bullshit if I tried. I can’t help it — the thought is spooking me on some level. At the very least he’s Gregg Stillson.

Just Around The Corner

Serious jihadists surely understand that an optimum time to strike the U.S. with a major terrorist act will be after Donald Trump takes the oath of office. Optimum because there’s a high likelihood that Trump will strike back all the harder, that he and his hardline advisers will go ballistic, and in so doing they will greatly intensify the U.S.-vs.-Islam divide that terrorists have been hoping for all along. For them, Trump will be the gift that keeps on giving. You know this is what the ISIS guys are telling each other now. A blustery, trigger-happy loose cannon in the Oval Office? Allahu Akbar!

“I’m afraid the adversaries overseas see us as a sitting duck of provocation…with a person who will lash back,” Ralph Nader told The National‘s Wendy Mesley. This is indicated by the president-elect is hiring “warfare people,” Nader explained.

No Silence Screenings Within BFCA Deadline

Despite a reported decision by Paramount to screen Martin Scorsese‘s Silence for members of the National Board of Review on 11.19 (i.e., yesterday) and members of the New York Film Critics Circle and Los Angeles Film Critics Association on 11.30, the studio is declining to screen it for the Broadcast Film Critics Association prior to the org’s initial nomination deadline of 11.29.

A Paramount rep informed me a week ago that BFCA honcho John De Simio was told in early November that the studio “would not be able to screen for BFCA consideration due to the fact that its 350 members are located in over 40 cities in 2 countries.” This was apparently due to Scorsese still working on the film as of 11.14 (per Scorsese’s 42West rep), the lateness of which apparently made screenings for BFCA hinterland critics a logistical impossibility.

If I were running the BFCA I would have asked Paramount to at least screen Silence for the 130 BFCA critics who live in New York and Los Angeles. This would have allowed those 130 members (i.e., a little less than half of the total BFCA membership, but better 130 viewers than none at all) to vote yea or nay on whether to nominate Scorsese’s film for general balloting by December 9th.

It hasn’t been made clear to me that the BFCA in fact sought such an arrangement, but they certainly should have. It’s just not cool to be silent on Silence when other players are seeing it and voting within the vicinity of 12.1.

Right now, to repeat, three major orgs — NBR, NYFCC and LAFCA — will see and vote on Silence within their respective deadlines, but the BFCA has been left out in the cold.

Remember also that 11.8 Deadline report about Paramount screening Silence for 400 Jesuit priests in Rome before the end of this month.

Key West Film Festival Wrap-Up

MTV movie critic Amy Nicholson (who fell ill last night to a combination of bad shellfish and a series of Mojitos) during Key West Film Festival chat with Rolling Stone‘s David Fear.

Beach at Key West’s Zachary Taylor State Park.

Celebrated costumer designer Mary Zophres (La La Land, almost all of the Coen brothers films) was honored at last night’s Key West Film Festival award ceremony.

Corner of Margaret and Southard Street, Key West.

Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn riffing about just-created KWFF critics award during last night’s ceremony. Kohn and longtime g.f. Liz Bloomfield, an accountant for NYC’s Marianne Boesky gallery, got married in Key West two days ago. Congrats & best wishes!

Newlyweds Liz Bloomfield, Eric Kohn during KWFF beach party that preceded the Saturday night award ceremonies.

Newlyweds Liz Bloomfield, Eric Kohn during KWFF beach party that preceded the Saturday night award ceremonies. “Get This Man Out Of Here!”

A few bad apples have made it into White House over the last 200-plus years (Warren G. Harding, Millard Fillmore, George W. Bush, Ulysses S. Grant, James Buchanan, Andrew Jackson), but Donald Trump is a breed apart — temperamentally unhinged (how many angry Hamilton tweets so far?), flagrantly corrupt ($25 million Trump University settlement), flagrantly racist (Jeff Sessions nominated as Attorney General), nakedly opportunistic (“stay to play” hotel promotion with Indian businessmen), climate change-denying (Myron Ebell is his chief environmental adviser), a believer in hardcore ideological adherence over measured temperance (Steve Bannon as White House Cromwell, Islamopohobic Michael Flynn and Mike Pompeo named as National Security Adviser and CIA chief, respectively)…the cray doesn’t stop and Trump is just getting started. And who helped bring this about in a minor but undeniable way? Jimmy Fallon. And you know who else? To some extent the Clinton-colluding Democratic National Committee.

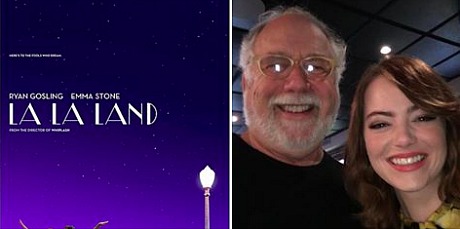

“Nice” Is Like Vanilla Ice Cream At A Summer Picnic

Yesterday morning there was an Academy member screening of Damian Chazelle‘s La La Land, and then a buffet luncheon at Craig’s on Melrose. A few hours later producer Jonathan Dana wrote on Facebook that he felt “fortunate to experience La La Land, one of the leading contenders for Oscar in about a dozen categories. When you see talent like this at play, it’s hard to stay totally bummed, at least until you pass a TV tuned to any sort of news. Go see this movie. Soon. It will enliven your spirits.

“And the filmmakers are the nicest people. And Emma Stone? Beautiful, smart, engaged and endearing. Lunch was great too. Lucky me.”

Jonathan Dana, La La Land star Emma Stone during yesterday’s luncheon at Craig’s on Melrose.

Nobody is a bigger fan of La La Land than myself, and while I’ve never chatted with Stone Dana is 100% correct in describing Chazelle as an entirely likable guy. I know Chazelle very slightly and can say he skillfully hides the fact that, like all accomplished artists, he’s a bit of a fretter and a worry wart. But also a straight shooter. Chazelle looks you in the eye and seems to actually mean what he says, which is unusual in Hollywood circles. But to Hollywood Elsewhere the word “nice” is like chalk on a blackboard.

Wells to Dana: “Sorry I missed the luncheon. One question, Jonathan: The La La Land guys are ‘the nicest,’ you say. Good to hear. We should all strive to be nice every day of our lives and twice on Sundays. But what else are they gonna be at an Oscar-season luncheon? Snippy? Snide? Sullen? Saying they were ‘the nicest’ is like saying the snowfall that fell last night in Moscow is ‘the whitest.'”

Will “Kakistocracy” Catch On, Or Is It Too Greek-Sounding?

“Seven days may not be enough time to fully assess any new leader, especially in the case of Trump, whose first week was marked by seeming chaos in his efforts to put together an Administration. But what we’ve learned so far about the least-experienced President-elect in history is as troubling and ominous as his critics have feared. The Greeks have a word for the emerging Trump Administration: kakistocracy. The American Heritage Dictionary defines it as a ‘government by the least qualified or most unprincipled citizens.’ Webster’s is simpler: ‘government by the worst people.'” — from recently posted Ryan Lizza column in The New Yorker, “Donald Trump’s First, Alarming Week As President-Elect” (11.16.16).

I blame Jimmy Fallon for this, to some extent. I really do. Fucking Jimmy Fallon. And the older, under-educated black voters who gave Bernie Sanders the back of their hand in the Southern primaries. And the more I think about it, the more I blame Hillary “Apocalypse-bringer” Clinton for being such a lethally non-charismatic candidate and more precisely the jaded and entrenched Democratic National Committee elites, primarily personified by the loathsome Debbie Wasserman Schultz, who worked and schemed so hard against Bernie.

Costner’s Hidden Figures Boss Is Portrait of Fairness and Decency

Yesterday I did a phoner with Kevin Costner, who brings a settled, fair-minded authority and decency to his performance as “Al Harrison” in Ted Melfi‘s Hidden Figures (Fox Searchlight, 12.25). There are some older actors who can just walk into a room without saying a word, and right away you relax. Because there’s something square and sensible about them. Costner is definitely one of those guys, and in every one of his Hidden Figures scenes, you know things will be more or less okay. Or that fairness will eventually come to pass.

Kevin Costner as Space Task Group honcho “Al Harrison,” a composite character partly based on the late Robert Gilruth.

Based on Margaret Lee Shetterly‘s same-titled book, Hidden Figures (which everyone likes) is a Kennedy-era tale of three female African-American mathematicians– Taraji P. Henson‘s Katherine Johnson, Octavia Spencer‘s Dorothy Vaughan, Janele Monae‘s Mary Jackson — who earned respect and advancement in the early years of America’s space program. In particular Johnson’s laser-like assessments were key to the success of John Glenn‘s historic 1962 orbital flight.

They all worked under NASA’s Space Task Group, which Harrison, in the realm of the film, the big boss of. And good old Kevin, a slightly bulky, mild-mannered figure in glasses, white dress shirt and skinny tie, is the guy who gives Johnson/Henson a fair shake and a respectful salute.

The standout moment is when Harrison singlehandedly desegregates the white vs. colored bathroom system at the Space Task Group’s headquarters (which was located in Langley, Virginia) with a sledgehammer or crowbar or something along those lines.

And yet Harrison isn’t presented as some heroic lead-the-charge type. He’s just a pragmatic technician-politician who wants to get the job done fast and accurately, and who therefore respects anyone with the brains and know-how to substantially help in that effort.

Lawrence Kasdan’s Grand Canyon

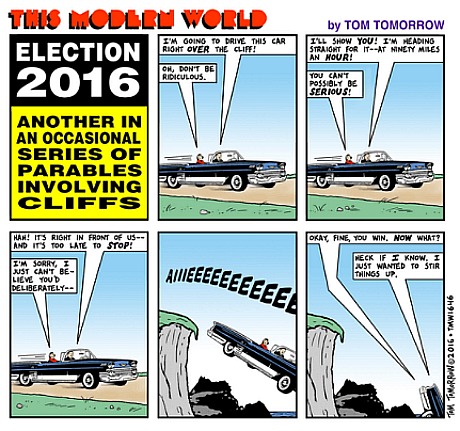

Posted five days ago (11.14) on Daily Kos:

The Heaven’s Gate-Like Rejection of Billy Lynn

In an 11.18 N.Y. Times piece by Ben Kenigsberg (“The Images in Billy Lynn? Razor Sharp. Your Eyes? Bewildered”), high-def pioneer Douglas Trumbull says he was unhappy with the venue for the 120-frame-per-second projection of Billy Lynn during the New York Film Festival. “I was really upset…that it was in a very narrow, small-screen theater,” Trumbull says.

My feelings exactly. “I felt crestfallen when I walked into the almost shoebox-sized AMC Lincoln Square theatre that Billy Lynn was projected in, ” I wrote on 10.15. “It was as if I was sitting in some nondescript megaplex in Tampa or Baton Rouge.”

I remain stunned that the critical elite dismissed Billy Lynn with such uniformity. The Heaven’s Gate-Like rejection of Ang Lee‘s film happened without remorse, without even an expression of mixed feelings. Critics and public alike dumped it like a McDonald’s Big Mac wrapper in a trash bin. For me Billy Lynn‘s HFR format elevated what would have otherwise been just another modest, dialogue-driven, Playhouse 90-styled drama. Is there anyone who found the 120-frame-per-second version at least interesting?

Trying again: at the very least all theatrically-aimed films should be shot in at least a 30 fps format, and all CG fantasy crap should definitely be captured in HFR (60 or even 48 fps would suffice). Action footage is always more mesmerizing if you remove the blur factor.