This, for me, is the very best of the five Wes Anderson ATT tube spots. Like Anderson’s popular American Express commercial from a couple of years ago, they’re all about a keyed-up character/pitchperson moving from one set to another without cuts. The idea is that nobody works in any one place anymore. In a sense, we all work in “Hollyarkizonasouthamaryland.”

Jeffrey Wells

Jeffrey Wells

Self-amputations & surgeries

A day or two ago New York magazine film critic David Edelstein became the latest big-name cineaste to launch a blog. He’s calling it “The Projectionist.” Today’s riff, in honor of Peter Fonda‘s endurance of bullet excavating in 3:10 to Yuma and Javier Bardem‘s oozy leg-surgery work in No Country for Old Men, asks readers to name their favorite scene in which a wounded character self-performs or receives some kind of crude medical procedure.

My favorite is Walter Slezak slicing off half of William Bendix‘s leg with a jackknife in Alfred Hitchcock‘s Lifeboat. Bendix doesn’t scream (he’s passed out from having chugged a half-bottle of brandy) but fellow lifeboat passengers Tallulah Bankhead and Hume Cronyn (or am I thinking of Henry Hull?) can’t look at what’s happening after 15 or 20 seconds’ worth. And then someone tosses Bendix’s left boot (i.e., the one he won’t need any more) and it goes thoomp on the hull of the boat.

The Lumet metaphor

Every so often the buyers (i.e., distribution reps) totally miss out on a film’s importance and marketability, and this was certainly the case with Toronto buyers and Sidney Lumet‘s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead. It’s even the case right now among certain journalists who don’t seem to fully understand that this modern-day Greek tragedy/family-crime film — unquestionably among the top flicks of ’07 — is well positioned to score with critics groups and Academy members between early December and mid January ’08.

Sidney Lumet receiving Lifetime Achievement “gold watch” Oscar from Al Pacino at Academy Award telecast on 2.27.05 —

The selling point with the latter group won’t just be the film (which, in a perfect world, would be enough in itself), but the metaphor of a spunky 83 year-old director whacking a fastball into the left field bleachers. Most directors of Lumet’s age are happy to be in good health and be invited to take part in an occasional film festival tribute. Lumet having produced the best film of his career since Prince of the City can be read (if you’re so inclined) as a blow against ageism in every sector of the industry. Older Academy members are going to feel at least somewhat roused by this, and consider Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead accordingly.

I believe that BTDKYD is an easy candidate for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor (Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Albert Finney, Ethan Hawke…are any of these guys leads?…possibly Hoffman…I can’t decide) and Best Supporting Actress (Marisa Tomei).

Carr on Iraq-Afghanistan films

In his first fall ’07 piece about awards-season Hollywood fare, N.Y. Times media columnist David Carr wonders if all the Iraq-Afghanistan war films opening over the next few months — In The Valley of Elah, Grace Is Gone, Stop Loss, Nothing Is Private, Lions for Lambs, Charlie Wilson’s War and Redacted — are going to meet with any box-office success.

Carr seems at least half persuaded that they may not. The tide of anti-war feeling across the U.S. “is bringing a wave of films about a war that most Americans wish would go away,” he writes.

“Historically, audiences enter the theater in pursuit of counter-programming as an antidote to reality,” he notes. “They’d generally prefer to see Meryl Streep inhabiting Anna Wintour in The Devil Wears Prada rather than playing a seasoned reporter who covers a country that seems to be in the midst of melting down, as she does in Lions for Lambs.”

Why? Because millions of people out there are walking expressions of doped-up lifestyles (i.e., addicted to alcohol, cell phones, general affluence, fatty foods, TV, Tivos, iPods, iPhones, SUVs, various medications, cigarettes and what-have-you …anything that will filter out reality) and states of total political denial.

“And these films have to compete not only with one another, but also with the drumbeat of the news media’s daily coverage of the Iraq war. Another I.E.D., another four Americans dead. Now, who wants popcorn with that?”

One HE dispute: Carr writes that the above films “all take as their central concern the price of America’s military and security activities since the attacks of Sept. 11.” But that’s not true as far as one of these films are concerned, and it’s a stretch with another.

Nothing is Private is a period piece (set in a Houston suburb in ’90 and early ’91, around the time of the Gulf War) that obviously reflects upon American attitudes about Middle Eastern natives now and before, but it’s flat-out wrong to say that its “central concern” is U.S. military and security activities since the World Trade Center attacks. Charlie Wilson’s War also sends out strong echoes about the 9.11disaster (particularly at the very end), but it’s an early ’80s period dramedy about the covert arming of the Afghanistan Muhjadeen in their fight against Russian invaders.

Fergusion disputes

In an N.Y. Times Op-Ed video, No End in Sight director Charles Ferguson rebuts claims made by former chief of Iraq occupation forces L. Paul Bremer III in a 9.6.07 op-ed piece called “How I Didn’t Dismantle Iraq’s Army,” claiming that top “American officials approved the decision to disband the Iraqi army” and not he alone.

Margot at the Wedding

I mentioned two days ago what a nervy, exacting and well-sculpted film Margot at the Wedding (Paramount Vantage, 11.16) is, and that Noah Baumbach‘s direction and writing, at the very least, deserve respect for having produced the gnarliest ensemble piece of the 21st Century.

I was taken, in other words, by the boldness in making a film about a family reunion that is so startlingly cold and strange and unconcerned with audience engagement.

There’s plenty of time to get into this down the road, but I saw Margot at the Toronto Film Festival, and I don’t want to imply a derisive or dismissive attitude by being silent. I didn’t “like” it very much, but at no point did I feel I was watching a meltdown or a car wreck. It’s a very well condensed, carefully layered study of some very screwed-up people. It just doesn’t care to tell a story that provides “answers” or any sort of parting of the clouds, or what most of us would consider a sufficient number of laughs.

If for no other reason, Margot is worth grappling with because of Baumbach’s one master stroke, which was to have the the film embody or emulate the deranged self-absorption of the characters.

The principal nutters are played by Nicole Kidman, Jennifer Jason Leigh and Jack Black, but every character in the film (except for Kidman’s androgynous son, whose name escapes, and her ex-husband, played by John Turturro) would have been thrown into Bedlam if they’d lived in London of the mid 1800s.

As we soon discover in this warped family get-together piece, nobody gives a damn about anything except for the fickle meditations swirling around in their heads, and Baumbach doesn’t give a damn about anything either (certainly not the reactions likely to be shared by average viewers).

What is the most hateful, go-away quality that anyone can possess aside from being a serial killer or having lethal gas or halitosis issues or lacking the ability to control your bowels? Manic self-obsession, or the inability to pay the slightest attention to the thoughts, feelings and needs of others.

This is the affliction that permeates Margot at the Wedding. Some have said it cripples it, but I disagree. Baumbach’s commitment to this mental-emotional state in his characters is so rapt and uncompromised that it’s almost thrilling. “Almost,” I say. You certainly can’t say Margot at the Wedding isn’t hard-core.

Imagine a modern Chekhov play peopled by an assortment of Hannibal Lecters without the cannibalism, the wit and the lacerating insights.

Margot‘s/Baumbach’s only two flaws are (a) not dealing satisfactorily with those ghastly pig-butchering neighbors who live on the other side of the fence in a ramshackle house, and (b) being cavalier about the cutting down of a large family tree that borders the two properties.

Trees are holy, sacred things — especially big ones — and should only be cut down if safety absolutely requires it. The pig-butchers want it taken down because of a root problem in their yard, but this is never really disputed (not vigorously) or explored, and before you know it Black is cutting a pie into the main trunk with a chain saw, and he doesn’t know how. For a tree-lover like myself it was like watching him suffocate a family dog or cat with a pillow.

I used to be a tree surgeon, and there’s a way to take a tree down. You climb up to the top, tie in, and drop down to the lowest level of leaders or branches and start sawing them off, one by one, as you work your way up. The idea is to create a branch-less totem pole, which you then drop onto the “bed” you’ve made of leaders and branches. In the film Black just drops the whole thing on top of a wedding tent — an act that temporarily symbolizes an end to his forthcoming wedding to Leigh.

I’ll re-examine this film four or five weeks from now. It’s partly infuriating, but it’s never uninteresting. I’d like to see it again and think it through some more.

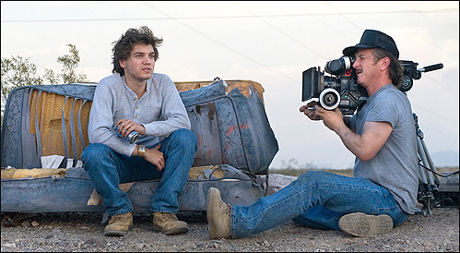

McGrath, Zlotnick & “Into The Wild”

I couldn’t find a strong pull-quote from Charles McGrath‘s 9.16 N.Y. Times piece about Sean Penn and the making of Into The Wild (Paramount Vantage, 9.21 limited), although it covers the territory pretty well. The photo, however, of Penn filming Wild star Emile Hirsch, provided by Paramount Vantage photographer-guy Chuck Zlotnick, has a quality. Something to do with two movie stars “working,” in a sense, with a beat-to-shit couch.

Ebert on “Elah”

Last Friday Rogert Ebert delivered, for my money, the most perceptive and best-written review of In The Valley of Elah that I’ve seen anywhere.

“I don’t think there’s a scene in the movie that could be criticized as ‘acting,’with quotation marks,” Ebert observes. “When Susan Sarandon, who has already lost one son to the Army, now finds she has lost both, what she says to [her husband] Tommy Lee Jones over the telephone is filled with bitter emotion but not given a hint of emotional spin. She says it the way a woman would, if she had held the same conversation with this man for a lifetime.

“The movie is about determination, doggedness, duty and the ways a war changes a man. There is no release or climax at the end, just closure. Even the final dramatic gesture only says exactly what Deerfield explained earlier that it says, and nothing else.

“That tone follows through to the movie’s consideration of the war itself. Those who call In the Valley of Elahanti-Iraq war will not have been paying attention. It doesn’t give a damn where the war is being fought. Hank Deerfield isn’t politically opposed to the war. He just wants to find out how his son came all the way home from Iraq and ended up in charred pieces in a field. Because his experience in Vietnam apparently had a lot to do with crime investigation, he’s able to use intelligence as well as instinct.

“And observe how Charlize Theron, as the detective, observes him, takes what she can use and adds what she draws from her own experience.”

Ebert got one tiny thing wrong, though. He quotes an early back-and-forth in which Jones tells Sarandon he’s going to drive to the New Mexico military base where his son was stationed and do some poking around. “It’s a two-day drive,” she says. Jones’ reply, according to Ebert, is “Not the way I’ll drive it.” Nope — he actually says, “For some people.”

Joe Wright vs. Marlon Brando

“To me, naturalism is the death of drama. Lee Strasberg came along and the Method fucked everything up. I find people like Celia Johnson are my favorite actors. I was brought up on films like Brief Encounter, and for me they expressed enormous truth. Marlon Brando does not have the monopoly on truth!” — Atonement director Joe Wright, as quoted in the trivia/bio section of his IMDB page.

Merkin on Wilson and melancholia

“The revelation that Owen Wilson may be afflicted with a physiological vulnerability to the downward pull — to the sort of self- annihilating impulse best described in William Styron‘s Darkness Visible — simultaneously fascinates us and causes us to avert our gaze,” writes Daphne Merkin in Sunday’s [9.16] N.Y. Times.

“However you parse Wilson’s desperate act, it is clear that in an instant-fix, cure-all culture — one in which we habitually reduce fraught real-life dramas into smart-alecky quips on late-night talk shows — we want instant-fix, cure-all answers. Addiction and recovery sagas are by now more boring than heartrending, but they go down smoothly and are media-pleasing.

“[And yet] the romance of melancholy — a style of self-presentation marked by an appealing air of ennui — has been with us since Hamlet. It is perhaps best expressed in the opening of Chekhov‘s The Seagull, when Masha, asked why she always wears black, replies, ‘I am in mourning for my life.’ But a poetic conception that tethers creativity to a despondent temperament is also misleading, discounting as it does how unproductively crippling the malady can be.

“Depression — the real hard stuff — is not chic, and it doesn’t sell tickets. It is a clinical illness urgently requiring treatment, usually hit-or-miss medication that tinkers with serotonin or dopamine levels. I am referring to the sort of condition that subverts lives, making it difficult to talk to people and impossible to leave the house. At its worst, it can spiral into the sort of suicidal ideation that requires hospitalization, or into suicide.”

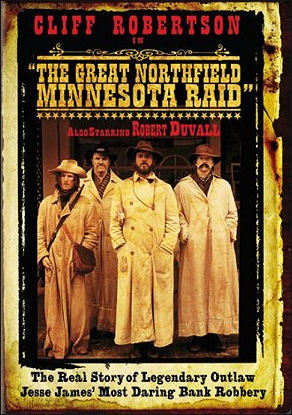

Northfield Minnesota Raid DVD

A spanking new DVD of Phil Kaufman‘s The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid (’72) — a not-great but well-worth-watching western about the biggest fiasco to befall the James-Younger gang — will be for sale on 9.25. It’s a vibrant example of Kaufman when he was really and truly Kaufman (i.e., pre-Right Stuff, pre-Henry and June, pre-Quills, etc.). A great cast — Cliff Robertson (Cole Younger), Robert Duvall (Jesse James), Luke Askew, R.G. Armstrong, Dana Elcar, Donald Moffat — and only 91 minutes long.

Swinton, fat rolls, eating pie

The Times Online‘s Kate Muir informs that Michael Clayton costar Tilda Swinton, while playing an American executive so gripped by vice-like ambition and desperation that she hires a killing to save her career, “was attracted to the miserable, lonely underwear scene.

“Alone in her hotel room, Swinton’s character, Karen Crowder, sits before the dressing-table mirror rehearsing a corporate speech. She’s in her bra, and a middle-aged droop of flesh sags beneath the strap on her back.

“‘That image struck me very early on when I was reading the script,’ Swinton recalls fondly. ‘It was one of the things that made me want to do the film — it made her seem vulnerable. She needed to have a certain kind of body, which I built with the help of rather a lot of pie.'”

I’ve never been so relieved that I don’t like pie as I am right now. Quentin Tarantino has written about eating pie in his scripts (Natural Born Killers, True Romance), and you can see today that pie (among other things) has had its way with him. Has anyone noticed how the so-called Key Lime pie that Woody Harrelson orders in NBK isn’t Key Lime pie at all, but a kind of bullshit Dunkin’ Donuts lime-jello thing?