With each new failed attempt to recapture the lustre of the first two Stars Wars films, the flickering flame becomes smaller, weaker, sadder. The prequels injected poison, and the sequels…well, yes, no and maybe. Is the fanbase even capable of understanding that it’s fucking over…can they get that simple fact through their thick heads? The only sensible response to the news about Taika Waititi being officially locked to direct and co-write a new Star Wars flick is “oh, Jesus God…another one?” The added blast about 1917 co-writer Krysty Wilson-Cairns co-penning the script with Waititi means nothing….less than nothing.

Jeffrey Wells

Jeffrey Wells

Beware of Anyone Who Says “Wow”

…while beginning to answer a complex question. On the other hand, the “addiction to growth” mentality is a profoundly serious problem. Michael Moore: “The word ‘enough’ is the dirtiest word in capitalism, because there’s not supposed to be any such thing as ‘enough’…it’s always more, more, more.”

No Sale

If you think I’m going to adjust my recollections of the George W. Bush presidency and perhaps even offer an historical upgrade because (a) Bush has just released a thoughtful and compassionate video about the pandemic, (b) he’s now being profiled by a new PBS “American Experience” documentary, and (c) he was a somewhat more responsible and conventional-minded president than Donald Trump has shown himself to be…if you think I’m about a give this second-rate man a pass, you’ve got another think coming.

You Want It Straight?

In yesterday’s comment thread under “Says Wrong Thing, Works Anyway” post, Grandpappy Amos wrote that Woody Allen‘s Crimes and Misdemeanors (’89) qualifies as an ethically flawed artistic success because it “shows that evil seems to get actually rewarded.”

This morning I replied as follows: “Incorrect. Crimes and Misdemeanors is about negotiating an arrangement with ‘the eyes of God.’ It’s about the ability of a wealthy and respected man (Martin Landau‘s “Judah Rosenthal”) to lapse into panic and rage and finally evil in order to protect his status and income. It’s also about how guilt can drive a person half-crazy until, like a fog lifting, it all seems to lessen and then more or less evaporate. So evil isn’t ‘rewarded’ but afforded a certain accommodation.”

Wiki slice: The universe is a dark and indifferent place which human beings fill with love, in the hope that it will give meaning to the cavernous void.

Great Depression 2

The latest anti-Trump ad by the Lincoln Project good guys (George T. Conway III, Steve Schmidt, John Weaver, Rick Wilson).

Joseph Losey’s “Accident In His Pants”

From “Full Disclosure: An Interview with standup comedian and former Celebrity Apprentice talent handler Noel Casler,” by PREVAILS’s Gregg Olear (posted on 5.1):

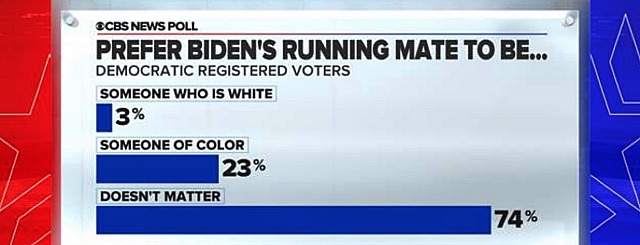

If I Was Biden, I’d Pick…

Joe Biden‘s vice-president can’t shouldn’t be chosen for cosmetic or charismatic reasons. The right vp would have to be ready to step into the Oval Office on a moment’s notice, and with Uncle Joe you have to consider what could happen in a year or two or three, given his age and whatnot.

For me the ideal partner would be Elizabeth Warren, but at the same time I’m not sure she’s the best choice from an electoral perspective, as her Democratic primary campaign never really connected and she never polled well in battleground states.

Kamala Harris is my second choice, and Susan Rice my third. Stacey Abrams is brilliant and extra-articulate and forceful — you tell me if she’d be a knockout campaigner or major ticket enhancer. Michigan’s Gretchen Whitmer seems a bit wet behind the ears but maybe not.

Says Wrong Thing, Works Anyway

It takes a certain amount of character and maturity to simultaneously walk and chew gum about a certain film — to be able to disagree with the content (or some aspect of it) but at the same time admire the chops or the expertise with which it casts a certain emotional spell.

If wokesters disagree with what a film is saying, they’ll write it off without a second thought. Serious cineastes take a broader view. They may not respect or even despise where a film is coming from but the reputable ones can’t reject it entirely if it hits the emotional mark, or if it’s superbly made.

The oldest example is Leni Reifenstahl‘s Triumph of the Will — reprehensible content, mesmerizing technique.

A recent example is Peter Farrelly‘s Green Book, which a chorus of cranky Shallow Hals derided for daring to operate within the realm of 1962 and thereby not in synch with 21st Century wokester values. I knew all that, but there was no denying that Farrelly’s film was emotionally affecting — that the connection between Viggo Mortensen and Mahershala Ali‘s characters carried a kindly, comforting current.

Jean Luc Godard was probably the first serious film demon to acknowledge this dichotomy, In a Cahiers du Cinema piece Godard admitted to being seized with affection for John Wayne‘s Ethan Edwards at the end of The Searchers when he picks up Natalie Wood and says, “Let’s go home, Debbie.” This is a “dishonest” moment from a 20th Century perspective as Ethan is a racist sonuvabitch, and there’s no way he’s going to renounce his gut feelings at the very last minute. But for Godard, the moment was transcendent.

I revisited this idea yesterday when I re-posted a Gunga Din riff from 12.24.17: “Otis Ferguson‘s review of this 1939 adventure flick called it a racist and arrogant celebration of British colonial rule. And yet I’ve been emotionally touched and roused by this film all my life. The last half-hour of Gunga Din is perfect, but it ends with Sam Jaffe‘s Indian ‘bhisti’ basking in post-mortem nirvana over having been accepted as a British soldier.” An appalling idea when you think about it, but it works.

I’ve always hated the shallow fantasy notion of superheroes and the corporate, FX-dependent theology of Marvel and D.C. films, but from time to time I’ve been surprised to find myself buying into the bullshit, Avengers: Endgame being the most recent example.

A couple of times I’ve mentioned how Billy Wilder‘s The Spirit of St. Louis says the wrong things by (a) ignoring the dark underside of Charles Lindbergh — “a nativist anti-Semite who admired the fascist state and urged the United States to stay out of the war because Nazi victory was certain,” as an HE commenter once put it — and (b) shamelessly embracing the idea of heavenly assistance just before the exhausted Lindbergh (James Stewart) is about to land his plane at Le Bourget field in Paris. He starts to lose it — freaking and whimpering over a sudden inability to focus on the basics of landing a plane. Then he thinks back to a “flying prayer” that a priest had passed on, and he blurts out, “Oh, God, help me.” And of course he lands safely. It’s a cheap Sunday-school trick, but Stewart’s acting and Franz Waxman‘s music sells it.

“Suburban Facebook Empathy Moms”

Despite my gender, I believe that I’m a kind of West Hollywood version of a Suburban Facebook Empathy Mom. I grew up in suburbia (New Jersey, Connecticut) so I get that whole thing. I poke around Facebook on a daily basis so that’s covered. I know what it is to empathize with anyone going through a difficult time, as no one feels the pain and sorrow of existence in a cold and barren universe more deeply than myself. And I know what it’s like to be a “mom” in a certain sense because I loved my dear and departed mother (Nancy Wells), I’m a father of two lads (Jett and Dylan), I’m currently a kind of mother to two cats and I’ve been called a motherfucker from time to time.

“I’ll Never Be Young Again”

Leonardo DiCaprio was 19 or 20 when this MTV chat (posted a couple of weeks ago, allegedly taped on 2.5.95) happened. He says he was in Paris to finish shooting The Basketball Diaries, but how could that be when Diaries premiered at the ’05 Sundance Film Festival a couple of weeks earlier? He more likely was there to begin shooting Agnieszka Holland‘s Total Eclipse, right?

LDC’s actual quote about youth (at 4:38) is “I’ll never get to be young again…this is my time to be young.”

This reminds me of Mr. Robinson’s remark to Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate, after learning that Ben has just turned 21. Mr. Robinson (lighting a cigar): “That’s a helluva good age to be. Because Ben…?” Braddock: “Sir?” Mr Robinson: “You’ll never be young again.”

Arguably The Funniest Bit

…in John McNaughton and Richard Price‘s Mad Dog and Glory (’93). Even though the line — “Put the magazine down before you hurt yourself…okay, Harold?” — sounds like it might have been a Bill Murray ad-lib.