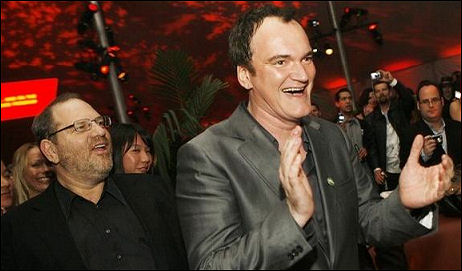

A couple of hours ago Nikki Finke posted an exclusive report concerning Quentin Tarantino‘s Inglorious Bastards project. She wrote that (a) the script went out yesterday (Monday) to Universal, Warner Bros and Paramount, and to Sony today, and (b) that there’s “a possibility” that Harvey Weinstein will be producing (along with Lawrence Bender) but not financing it, which “certainly adds fuel to those rumors that The Weinstein Co is having movie money woes.”

The question I would have asked if one of my agent sources had called me about this is “how many pages”? Is it, like, 180 or 200 pages? I ask because of that reported-about interview between original Inglorious Bastards director Enzo G. Castellari and Tarantino on the forthcoming three-disc DVD (out 7.29) of his 1978 film reveals that Tarantino’s new version will be a two-parter like Kill Bill. In other words, something that may be leisurely paced, elephantine, long.

If I was running production at one of the four studios, I would insist that everyone reading and making a call about Tarantino’s Bastards script should also see Castellari’s original 99-minute film, which came out in ’78. We all know that Tarantino routinely flavors his scripts with his sassy talky-talk, and that Bastards, though set in World War II, will completely ignore the idioms of G.I. speech at that time in favor of the Quentin music. Which is fine. But I would want to know if the “music” or perhaps the extra plotting is really worth the expense of making and releasing two movies. (If, that is, the script indeed runs around 180 or 200 pages. Maybe it doesn’t. Maybe the movie Tarantino talks about on the Bastards DVD is no more.)

It may also be that Tarantino’s Bastards has a natural “fighting weight” length of 180 minutes or longer, and no ifs, ands or buts. But I also might insist, depending on the length of the script, that the theatrical version of the film be shot and cut to run no more than 115 to 120 minutes, and that a three-hour version (or perhaps a Part I and Part II) be confined to the DVD market. Because I really wouldn’t want to go through any sort of Grindhouse-type experience.

And because I believe that any movie or novel or essay is always a little better if it’s been pruned and tightened to within an inch of its life. The Tarantino I’ve heard about all these years doesn’t know from pruning. He is no longer, by most accounts, the guy he was in ’92 or ’94 or even ’97. He seems to be someone who believes in and stokes the fires of his own legend, and who seems to have a sense of his own genius, invincibility and entitlement. Not a mentality, in short, that’s likely to produce something lean and mean.