Stephen Frears‘ Florence Foster Jenkins (Paramount, 8.12) is about the willingness of people to tolerate a musical atrocity in the name of kindness and compassion, but mainly because the titular offender — a real-life millionaire socialite (Meryl Streep) who couldn’t sing a lick but nonetheless insisted on performing opera in front of elite audiences from 1912 until her death in late 1944 — was stinking rich.

Because Jenkins was flush her common-law husband, St. Clair Bayfield (Hugh Grant), protected her from the truth. Because his lifestyle depended on it and because his attitude was “well, she loves music so where’s the harm?” That’s all the movie is, boiled down — a harmless indulgence. Bayfield indulged Florence, and now you, the audience, get to indulge Florence Foster Jenkins. I’ve seen it twice, and I’m not down on it. It’s a curiosity, and yet nimble and nicely made. Not precisely my cup but not bad. No animus.

The most winning performance is given by Simon Helberg as Cosme McMoon, Jenkins’ patient and compassionate pianist. Rebecca Ferguson, Nina Arianda and John Kavanagh costar.

Streep’s performance is well honed and appealing, in part because she allows you to feel that Jenkins was merely a deluded music fan and not, as I suspect was the case in real life, one of the most arrogant non-singers in world history. Streep will probably be nominated for Best Actress, but Grant almost certainly won’t be Best Supporting Actor nominated, as a Janelle Riley story in Variety suggested earlier today. It’s just too slight of a role.

You could say that Frears’ film is about an extremely perverse definition of love and sensitivity. It basically says that if a woman you care for a great deal is (a) absolutely dreadful at singing opera, (b) unable or unwilling to recognize how bad she is, and (c) insists upon singing for audiences nonetheless, the truly loving husband or friend will not only avoid confiding the awful truth but will do everything in his/her power to allow the singer to live inside her fantasy bubble, mainly by shielding her from honest reactions.

Streep, Frears, Grant during filming in Liverpool.

Moreover, the movie says that those who would speak frankly about the woman’s appalling lack of talent (not to mention her refusal to even consider what a brutal and gruesome thing her voice was) are insensitive and even cruel. The invisible subtitle of Frears film is “don’t be callous.” For the film is also saying that the only civilized and compassionate response to Florence Foster Jenkins is to embrace the movie’s billboard slogan — “Every voice deserves to be heard.”

Really?

I feel that a voice that threatens to shatter glass should not only be shunned but discouraged at all costs. I say that as a lover of music and a respecter of serious talent. The wheat must be separated from the chaff. Either you’re gifted or you’re not. I used to be a fairly mediocre drummer in a rock band, and I still remember that awful feeling in my stomach when I heard secondhand that a listener had said “your drummer sucks.” But life requires that we face up to things, which is for the best in the long run. Find your calling, accept your limitations, etc.

Jenkins’ voice was an affront to the very concept of music. But because she was rich she was allowed and in fact encouraged to indulge herself. What the film is really saying isn’t “every voice deserves to be heard” but “every rich person’s voice will be heard one way or the other, because non-rich people are usually inclined to indulge the wealthy in the hope that somehow their wealth will rub off on them.” This same system of tolerance applies to those who will pay to see Florence Foster Jenkins.

The movie is declaring that if you’re a somewhat cruel and dismissive person, you’ll say “well, this film is a bit ridiculous because the woman couldn’t sing at all so why do we have to suffer through all this terrible singing?” The movie is saying “please, you’re better than that…try a little tenderness…this woman loved music.”

Frears summed it up during a recent q & a in Westwood when he said something close to this: “You’re appalled by her singing but at the same time she breaks your heart.”

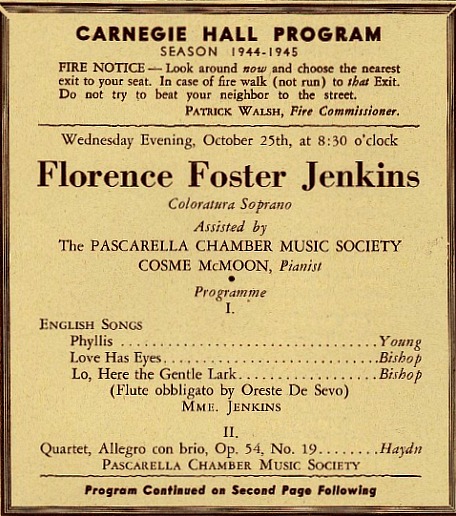

He’s right. There’s a moment at the very end when you do feel sorry for her. It happens when Jenkins/Streep reads a bluntly worded review by N.Y. Post columnist Earl Wilson, who attended Jenkins’ infamous Carnegie Hall concert (10.25.44) that the film is more or less about. Within minutes of reading Wilson’s review, which called her the worst singer ever and described the concert as “one of the weirdest mass jokes New York has ever seen,” the movie has Jenkins/Streep stumble across a New York street and collapse in the foyer of her apartment building. She’s with God a day or two later.

In actuality Jenkins suffered a heart attack five days after the concert while shopping in G. Schirmer’s music store. She died almost exactly a month later, on 11.26.44, at age 76.

In the film Wilson (Christian McKay), astonished by what he’s heard, leaves Jenkins’ Carnegie Hall performance early on and runs into Bayfield. Wilson really lets it rip when Bayfield tries to persuade him to stay and give Florence a chance. In actuality Wilson supposedly asked “Why?” “She loves music,” Bayfield replied. “If she loves music,” said Wilson, “why does she do this?”