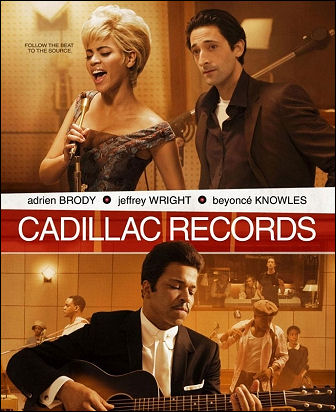

In the view of Variety‘s John Anderson, Darnell Martin‘s Cadillac Records (TriStar, 12.5) “approaches the blues with the enthusiasm of an overcaffeinated brass band, [but] nonetheless makes some kind of music, mostly because she mines a righteous, mythic sensibility out of the story of Leonard Chess, Muddy Waters and the birth of the Chicago blues.

“Jeffrey Wright‘s Waters is unforgettable, Eamonn Walker gives an unnerving performance as rival bluesman Howlin’ Wolf, and Beyonce Knowles‘ Etta James should put bottoms in seats.

“The second feature this year to focus on the same musicians, Cadillac Records takes a far broader approach than Jerry Zaks‘ Who Do You Love, which concentrated more on the conflicted character of Chess than on the artists he hired, promoted, profited from and, some say, exploited.

“In Cadillac Records, Adrien Brody cuts an appropriately oily figure as the man who founded Chess Records in 1956, while Wright delivers a performance of eloquent, simmering dignity as Waters — the first Chess star, one of the great vocalists in American music and the dramatic engine of Martin’s film.

“As a racial parable that couldn’t be timelier. Chess Records was a mixed marriage — the owner was a Polish immigrant, his artists were African-American, and much of the America they inhabited was hostile to any such arrangement. This all comes to a head after Chess signs Chuck Berry (a dryly funny Mos Def), whose hybridized pop sound had some promoters thinking he was a white country singer.

“Berry is the guy who puts Chess over the top; as someone says, they’re not sure what he’s playing, but it’s not the blues. But it sells, and it bridges the racial divide: In a scene duplicated in Who Do You Love, the velvet ropes separating whites and blacks at a Berry concert are toppled by the audience.

“That Martin later has Knowles reprise the entire racial psychology of America through James and her seemingly insoluble identity problems, by contrast, is overkill; Knowles gives a soulful portrayal, but her part of the movie seems to exist in another dimension entirely.

“The music — most of it performed by the actors themselves — has a real richness to it, if not quite the muscle of the Chess records themselves. Recording sessions are shot like live concerts; the club gigs feel sweaty and smoky. And Def’s Berry performances succeed in capturing what it felt like when the blues had a baby and they named it rock ‘n’ roll.”