Bennett Miller‘s Capote cost $7 million to make, and earned just shy of $50 million worldwide. I’d forgotten that. It made $28,750,530 domestic, $21,173,549 overseas for an exact total of $49,924,079.

I was visiting Miller’s lower Manhattan loft apartment around the same time, maybe a few weeks hence, I forget exactly when. But I distinctly recall Bennett showing me some original Richard Avdeon contact sheet photos of Truman Capote, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock, and for whatever reason Bennett happened to call Phillip Seymour Hoffman about something, and as he was saying goodbye he called him “Philly.”

I loved the idea of a distinguished hotshot actor being called Philly, and so I used it myself a few weeks later. I knew it was inappropriate to project an attitude of informal affection with a guy I didn’t know at all first-hand, but I couldn’t resist. I was immediately bitch-slapped, reprimanded, challenged, castigated, stomach-punched, dumped on, stabbed, karate-chopped, slashed and burned….”How dare you call him that? Who the hell do you think you are, some kind of insider?…soak yourself with gasoline and light yourself on fire!”

HE review, posted three or four weeks before the 9.30.05 opening: “I’m taken with Capote partly because it’s about a writer (Truman Capote) and the sometimes horrendously difficult process that goes into creating a first-rate piece of writing, and especially the various seductions and deceptions that all writers need to administer with skill and finesse to get a source to really cough up.

“And it’s about how this gamesmanship sometimes leads to emotional conflict and self-doubt and yet, when it pays off, a sense of tremendous satisfaction and even tranquility. I’ve been down this road, and it’s not for the faint of heart.

“I’m also convinced that Capote is exceptional on its own terms. It’s one of the two or three best films of the year so far — entertaining and also fascinating, quiet and low-key but never boring and frequently riveting, economical but fully stated, and wonderfully confident and relaxed in its own skin.

“And it delivers, in Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s performance as Capote, one of the most affecting emotional rides I’ve taken in this or any other year…a ride that’s full of undercurrents and feelings that are almost always in conflict (and which reveal conflict within Capote-the-character), and is about hurting this way and also that way and how these different woundings combine in Truman Capote to form a kind of perfect emotional storm.

“It’s finally about a writer initially playing the game but eventually the game turning around and playing him.

“Hoffman is right at the top of my list right now — he’s the guy to beat in the Best Actor category. Anyone who’s seen Capote and says he’s not in this position is averse to calling a spade a spade.

“I’m not talking about Hoffman doing a first-rate impression of a famously effeminate celebrity author of the ’60s and ’70s. I’m speaking of his ability to make us feel the presence of Capote’s extraordinary talent and sensitivity and arrogance…a self-amused cocky quality born of extraordinary smarts and a feisty temperament that could suddenly veer into aloofness or even cruelty and at other times devolve into childlike vulnerability.

“There’s always a sense of at least two and sometimes three or four rivers running through this character at once, all of it vibrating and churning around in Hoffman’s liquidy eyes and, when things get especially difficult, his nearly trembling pinkish-white face, and in the way he walks and gestures and shrieks with laughter at parties, and in the way he occasionally just stands utterly still. It’s an astonishing piece of work.

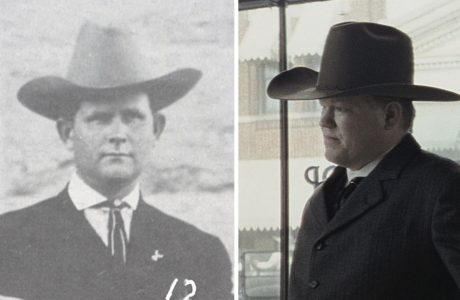

“A friend thinks Hoffman isn’t small enough to play Capote, who was about 5′ 2″. Other naysayers may be heard. There’s a tradition of straight actors portraying flamboyant queens (I’m thinking way back to Cliff Gorman’s performance in William Freidkin’s The Boys in the Band) that hasn’t dated all that well, but Hoffman is doing so much more in this film that the comparison isn’t worth mentioning.

I can’t stop re-running my favorite parts of Hoffman’s performance. There are so many lines and moments, but to describe them would only muck it up. Maybe later…

“Capote is fundamentally about “In Cold Blood,” Capote’s groundbreaking non-fiction novel that came out in early ’66.

The book was about the murder of the four members of the Clutter family of Holcomb, Kansas, and their killers, Dick Hickock (Mark Pellegrino) and Perry Smith (Clifton Collins, Jr.). The film is about Capote’s researching and writing of the book, a process that lasted from November 1959 until the summer of ’65, and which pretty much tore Capote to shreds.

The core material has to do with a kind of love affair that happened between Capote and Smith during the death-row interviews conducted by Capote from the time of the murderers’ conviction in early 1960 until the hangings of Smith and Hickock in April ’65. Capote fell in love with Smith because they had shared similar traumatic upbringings (alcoholic mothers, family suicides) and because Smith had certain poetic-artistic aspirations.

“’It’s like we grew up in the same house, except one day Perry went out the back door and I went out the front,’ Capote tells his longtime friend and confidante Nelle Harper Lee (Catherine Keener), the author of ‘To Kill a Mockingbird.’

“He really feels for Smith…you can see it, feel it…but Capote is scrutinizing enough to step back at every juncture and eyeball his relationship with Smith in literary terms. After persuading Smith to let him read his diaries, Capote tells Lee that this sad, doomed, hugely conflicted man is “a gold mine.”

“The fascination is in watching Capote play Smith like a pro while getting more and more caught up with him emotionally. He gets the two killers an attorney following their conviction so he can get their execution delayed so he can get their full story. And then he lies to Smith time and again.

“And after he’s gotten most of their story he begins to acknowledge that he wants them executed so his book will have a finale, even though his feelings for Smith have always been, as far as it goes, earnest.

“There’s a nice scene when Capote tells Kansas Bureau of Investigation chief Alvin Dewey (Chris Cooper) that he’s decided to call his book ‘In Cold Blood,’ and Dewey says, ‘Is that a reference to the crime, or the fact that you’re still talking to the killers?’

“When their long-delayed death sentences are finally at hand, Capote’s feelings come to a boil. His last meeting with them, moments before the end, is choice. Tears flooding his eyes, Capote tells them both (but particularly Perry), “I did everything I could…I truly did.” Which was true, in a manner of speaking.

I never expected Bennett Miller to direct Capote quite so well. He’s never helmed a feature and has mainly confined himself to TV commercials, although he directed a very fine 1998 documentary called The Cruise, a black-and-white portrait of the great Timothy “Speed” Levitch.

“To me, Capote feels as controlled and precise, as emotionally on-target and penetrating as any film by Louis Malle. You could run it with Damage and Atlantic City at the Museum of Modern Art, and it would feel like the exact same guy calling the shots.

“I was especially taken with Miller’s decision to shoot Capote in widescreen Panavision (2.39 to 1). Stories of this sort — internal, intimate, dialogue-driven — are usually shot in 1.85 to 1 (or on video). Was Miller thinking about creating some kind of visual relationship to Conrad Hall’s widescreen photography in Richard Brooks’ In Cold Blood, even though that 1967 film was shot in black and white?

“And a sincere tip of the hat to screenwriter Dan Futterman, who worked on the screenplay for a long time before getting it right. It’s based on Gerald Clarke’s Capote, which is probably the best Capote biography.

“Futterman has known Miller since they were twelve, and they’ve both known Hoffman since ’84 (i.e., the year Capote died of alcoholism) when they met at a summer theatre program in Saratoga Springs,

“Every performance in Capote feels rooted and lived-in…nobody seems to be “acting” in the slightest.