Why don’t technically-sophisticated, state-of-the-art space vehicles in recent space flicks (Life, Passengers, Gravity) have the ability to track oncoming objects and/or debris and alter their flight path in order to avoid collisions? Remember the oncoming-Russian-missile sequence in Dr. Strangelove (“confirmed…definite missile track…continue evasive action”) and how Slim Pickens‘ B-52 banked and swerved and did all it could to avoid the missile? And how they managed to see the missile coming with this amazing technology called “radar”? Why can’t these space vehicles, 1000 times more technically advanced than an early ’60s B52, detect an approaching threat and commence evasive action (ducking, dodging, swerving) to steer clear of harm’s way? I’ll tell you why they can’t. Because the filmmakers like collisions. The rule in these films is that if an object or a debris field of some kind is coming your way, YOUR SPACE VEHICLE IS GOING TO TAKE A BIG HIT, period. No radar, no escape…it’s a demolition derby up there.

cinema godz

Ford’s Bravery, Drinking, Sentimentality

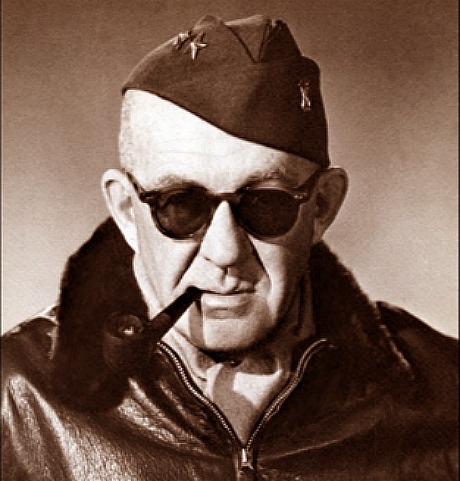

What terms or descriptions come to mind when you say the name John Ford? The first thing I think of is “revered auteur-level director,” the second is “exquisitely balanced visual compositions,” the third is “cranky personality,” the fourth is “Irish sentimentality” and the fifth is “enjoyed drinking too much.” But I have a new sixth term after seeing Five Came Back — “Sent home from Europe after going on a three-day bender after witnessing the horrors of D-Day.”

This is a shorthand summary, delivered by director Laurent Bouzereau and writer Mark Harris in the forthcoming three-part Netflix documentary, about why Ford’s work for the War Department ended soon after the D-Day invasion.

In yesterday’s rave review I wrote the following about this incident and also Ford’s post-WWII films: “Ford, who incurred the wrath of his military superiors after descending into a three-day alcoholic bender after witnessing the bloody D-Day slaughter (4000 Allied troops died on 6.6.44), became less of a Grapes of Wrath or Informer-styled social realist and increasingly devoted himself to Western myths and fables, which could be seen as a kind of sentimental retreat.”

Ford biographer Joseph McBride has read Harris’s 2014 book but hasn’t seen the Netflix doc, but he’s taken issue with the above-described summary and has passed along his own account of Ford’s activities and status following the D-Day invasion. I passed along McBride’s recap to Harris so he could respond or clarify.

What follows is (a) McBride’s D-Day account, (b) Harris’s response and (c) McBride’s dispute with my view that after the war Ford’s films invested more and more to Western myth and sentimental notions about the past.

McBride #1: “I cover the post-D-Day period in “Searching for John Ford“, pp. 397-404. Ford did go on a bender for a few days after his supervising of the massive D-Day filming operation for the U.S. Navy. (Ford was serving with the Navy and the OSS.) He was on a boat anchored near Omaha Beach when the invasion began on June 6, 1944, and hit the beach later that day.

“The OSS wrote of Ford, ‘After landing he visited all of his men in their various assignments, and served as a great inspiration by his total disregard of danger in order to get the job done.’ “The film footage shot by his cameramen and by automatic cameras on landing boats was sent to London for assembly into a secret film shown only to Churchill, FDR, and Stalin.

“I write that Ford went on a bender at a house in France serving as headquarters for a combat camera outfit of the Army Air Forces First Motion Picture Unit, after ‘badly needing to unwind from the supreme tension of the invasion,’ adding that he was ‘physically and emotionally spent.”

Eternal Fraternity of Cohen-Heads

I’ve been an admirer of director-writer Larry Cohen since the mid ’70s. I didn’t get him at first. My first impression was that he was making clever low-budget exploitation schlock, It’s Alive (’74) and God Told Me To (’76) being my first two samplings. I finally got him after seeing Q, The Winged Serpent (’82). I started to imagine that Cohen might be making dry exploitation film satires — that he might be half playing it straight for the sake of his investors but was also “in on the joke.” Or something like that. I’ve been running into Cohen and longtime pally Laurene Landon at Los Angeles parties and screenings for many years, and it’s good to see that Steve Mitchell‘s King Cohen is finally coming out. The talking heads include Martin Scorsese (who looks a good ten years younger in the trailer than he does today), John Landis, Michael Moriarty, Fred Williamson, Yaphet Kotto, Landon and several others.

Fanfare Meets Trepidation, Anxiety: Newman’s Five Came Back Theme

As noted in my Five Came Back review, Thomas Newman‘s main-title theme stands out like a sonuvabitch. It makes you think that John Ford, William Wyler, George Stevens, John Huston and Frank Capra were up to something more daring and dynamic than just shooting war footage, which of course they were. But the music announces this. It delivers an urgent, aggressive vibe along with a sense of “uh-oh, wait a minute…are we okay?”

Newman’s French horns or trombones or whatever aren’t Beethoven or Wagner-ish, but the notes aren’t as plain as they initially sound either. You could be hearing them in your head before a beach landing. Organized, aggressive, battalion-strength fanfare, but with the willies.

Newman’s theme is part of that tradition of swelling military music that includes Richard Rodgers‘ Victory at Sea and Jerry Goldsmith‘s main-title Patton theme, except Newman’s also includes an echo of John Williams‘ Olympics fanfare theme (and maybe even a dash of his Towering Inferno score).

Jeremy Turner (A Birder’s Guide to Everything, A Year in Space, Trophy) wrote all the Five Came Back music that isn’t heard in the opening and closing credits.

Again, the mp3.

“It’s Good To Be In The World…It’s Wonderful”

Trust the buzz: Laurent Bouzereau and Mark Harris‘ Five Came Back (Netflix, 3.31), a three-hour doc based on Harris’s 2014 book of the same title, is a knockout. Or at least it was for me. Call it an incisive, emotionally stirring, highly insightful saga of World War II, or rather the filming of it but in a broader sense the bruising reality of it. Like any good film Five Came Back swirls down, under, all around.

It focuses on five big-name Hollywood directors — John Ford, Frank Capra, William Wyler, George Stevens and John Huston — who put their Hollywood careers on hold during World War II in order to make propaganda-like documentaries (or doc-like propaganda films) for the U.S. War Department.

But it didn’t turn out that simply. While Capra devoted himself to producing several gung-ho esprit de corps films under the title of Why We Fight, Stevens, Ford, Wyler and Huston wound up capturing (and in a couple of instances recreating) harrowing scenes of real-life battle and carnage that not only shook them personally but led to periods of post-war melancholia as well as re-assessments of who they were and what kind of cinema they wanted to make. It also led to the making of their finest films, particularly in the case of Wyler (The Best Years of Our Lives), Capra (It’s A Wonderful Life) and Huston (Treasure of the Sierra Madre).

We’ve all have our impressions of World War II from this and that visual source (movies, docs, endless photos), but Millenials and perhaps even younger GenXers probably regard it as something that happened so long ago it’s in the same musty box as the Civil War. Five Came Back somehow makes this earth-shaking conflict seem more fierce and first-hand than it has since Saving Private Ryan (which is nearly 20 years old now, believe it or not).

This is largely, I feel, because of five present-day helmers — Steven Spielberg, Guillermo del Toro, Francis Coppola, Larry Kasdan and Paul Greengrass — passing along thoughts and musings about this great saga, each focusing on a specific director and storyline (Spielberg on Wyler, Kasdan on Stevens, Del Toro on Capra, Greengrass on Ford, Coppola on Huston). These guys sell the shit out of this thing, and you can only do that with conviction, intelligence and empathy.

All five of the WW II-era directors suffered wounds, bruises and traumas of one kind of another…nobody came out of it without some kind of limp.

Ford, who incurred the wrath of his military superiors after descending into a three-day alcoholic bender after witnessing the bloody D-Day slaughter (4000 Allied troops died on 6.6.44), became less of a Grapes of Wrath or Informer-styled social realist and increasingly devoted himself to Western myths, which could be seen as a kind of sentimental retreat.

Stevens, whose post-liberation footage of Dachau was used in Nuremberg war-crimes trials, wound up brooding for three or four years before finally getting back behind the camera to create his great American trilogy — A Place In The Sun (’51), Shane (’53) and Giant (’56) . He waited until the late ’50s to direct a WWII drama, The Diary of Anne Frank, that channeled or reflected his war experience.