What terms or descriptions come to mind when you say the name John Ford? The first thing I think of is “revered auteur-level director,” the second is “exquisitely balanced visual compositions,” the third is “cranky personality,” the fourth is “Irish sentimentality” and the fifth is “enjoyed drinking too much.” But I have a new sixth term after seeing Five Came Back — “Sent home from Europe after going on a three-day bender after witnessing the horrors of D-Day.”

This is a shorthand summary, delivered by director Laurent Bouzereau and writer Mark Harris in the forthcoming three-part Netflix documentary, about why Ford’s work for the War Department ended soon after the D-Day invasion.

In yesterday’s rave review I wrote the following about this incident and also Ford’s post-WWII films: “Ford, who incurred the wrath of his military superiors after descending into a three-day alcoholic bender after witnessing the bloody D-Day slaughter (4000 Allied troops died on 6.6.44), became less of a Grapes of Wrath or Informer-styled social realist and increasingly devoted himself to Western myths and fables, which could be seen as a kind of sentimental retreat.”

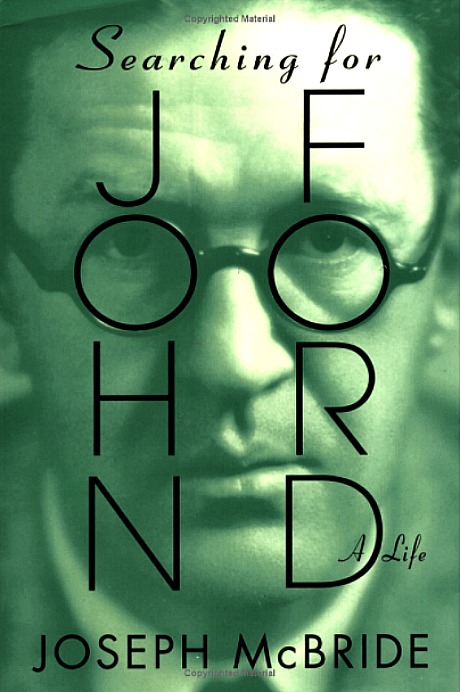

Ford biographer Joseph McBride has read Harris’s 2014 book but hasn’t seen the Netflix doc, but he’s taken issue with the above-described summary and has passed along his own account of Ford’s activities and status following the D-Day invasion. I passed along McBride’s recap to Harris so he could respond or clarify.

What follows is (a) McBride’s D-Day account, (b) Harris’s response and (c) McBride’s dispute with my view that after the war Ford’s films invested more and more to Western myth and sentimental notions about the past.

McBride #1: “I cover the post-D-Day period in “Searching for John Ford“, pp. 397-404. Ford did go on a bender for a few days after his supervising of the massive D-Day filming operation for the U.S. Navy. (Ford was serving with the Navy and the OSS.) He was on a boat anchored near Omaha Beach when the invasion began on June 6, 1944, and hit the beach later that day.

“The OSS wrote of Ford, ‘After landing he visited all of his men in their various assignments, and served as a great inspiration by his total disregard of danger in order to get the job done.’ “The film footage shot by his cameramen and by automatic cameras on landing boats was sent to London for assembly into a secret film shown only to Churchill, FDR, and Stalin.

“I write that Ford went on a bender at a house in France serving as headquarters for a combat camera outfit of the Army Air Forces First Motion Picture Unit, after ‘badly needing to unwind from the supreme tension of the invasion,’ adding that he was ‘physically and emotionally spent.”

“But after a few days of that, he went on the USS Augusta and then on June 15 or 16 he went on Navy Commander John Bulkeley‘s PT boat, which was patrolling the coast ‘to repel [German] E-boats coming into the assault area.’ Ford was on the boat during some of those attacks. Bulkeley told me that Ford did ‘exactly what any brave man would do — daring fate. He was no coward at all. He was like any typical Irishman there. He loved the excitement of it and he loved danger. He was just great.’

“Ford left the PT boat for two or three days to witness combat in Caen and then rejoined Bulkeley on the boat. Ford remained in France until July 29. Then he went to London. He went on another secret mission from July30 to August 4. Bulkeley told me Ford accompanied him on a mission to Yugoslavia that ‘dropped a bunch of people off and a bunch of ammunition and so forth.’

“Ford eventually requested that the Navy put him on inactive status (granted Oct. 20, 1944) so he could direct They Were Expendable, his great film about the war (based on Bulkeley’s exploits) for MGM. After making it and spending two months in Washington wrapping up the affairs of his Field Photo unit, Ford was released from Navy service on Sept. 29, 1945.”

Harris response: “Thank you for sharing McBride’s note with me. I read his biography of Ford, and also Scott Eyman’s, ‘Print the Legend’, both of which are excellent, and, of course, did my own research into Ford’s archives. If you read their books and mine, you’ll get, in all three, the same sequence of events (including the Bulkeley stuff) that McBride describes — but you’ll get different takes on how it unfolded and what it meant. (If you’re curious, I’m attaching a pic of the two pages of my book that deal with this.) Ford’s blackout drinking was a big problem for him even before the war. I sometimes say that if there were a sixth character in the book, it would be alcohol — it was a huge factor for Ford and no small part of Huston’s life as well.”

McBride #2: “I’m taking issue with your saying Ford avoided dealing with war after World War II and retreated from social issues into Westerns for sentimental reasons. In fact, Ford was obsessed with war in the period 1945-52. Some of the films he made then are also among his best work.

“Before he made The Quiet Man in 1952 — about a boxer who kills a man in the ring and flees the U.S. to escape violence in search of peace (a clear metaphor

for what we now call PTSD) — Ford made eleven other films in that period, and nine of them dealt with war or other forms of armed conflict. The two exceptions were the religious allegories The Fugitive (which is about a police state) and the western 3 Godfathers.

“After his great World War II film They Were Expendable in 1945, he dealt with World War II in When Willie Comes Marching Home, World War I in What Price Glory, and the Korean War in his 1951 documentary This Is Korea!. His postwar westerns include his Cavalry Trilogy (Fort Apache, She Wore A Yellow Ribbon and Fort Apache), which are set in the Indian Wars. His first postwar film, the western My Darling Clementine, is about the mythic Wyatt Earp, whom Ford shows trying to settle down by taming a town and killing the family who killed his brothers — another analogy with a returning veteran haunted by violence and finding it hard to escape it.

“Wagon Master similarly is about a group of peaceful Mormons traveling West in search of their ‘promised land’ who are held hostage by a family of outlaws and in a bitter irony have to rely on gunfire by their hired wagon master and his partner to save them. The outlaws in those two films are portrayed as pure evil, like the fascist enemy in World War II. Wagon Master also deals with religious intolerance and portrays Native Americans in a positive light.

“Ford did not avoid social issues after the war or just spin western myths. In fact, he explicitly debunks western mythology in Fort Apache (1948), which is an expose of the Custer legend, and which takes the side of the Indians. I found a letter a woman wrote Ford in that period asking why he was making westerns. He replied that it was safer to deal with social issues in a western than in a contemporary film. No one cared about westerns, so he could make a daring film such as Fort Apache and no one would notice.”

“Ford also had patriotic motives (somewhat in conflict with his other motives; Ford was always complex). He wrote in 1949, “Making western pictures of that era has been a crusade with me since the war.’ Pointing to the success of his cavalry films, he added, “I am sure that means there are millions of people left [in the U.S.] still proud of their country, their flag, and their traditions.” And since Ford was going independent after the war with his Argosy Pictures, like others who came back from the war, he was relying to some extent on the almost-guaranteed box-office appeal of westerns. He said, ‘When in doubt, make a western.'”