And I refuse to abide…sorry. “Myooney” to the death.

And I refuse to abide…sorry. “Myooney” to the death.

I’m naturally presuming that Disney’s half-animated, half-live-action Song of the South (’46) will never be seen again because of antiquated negative racial stereotypes contained in certain portions.

But from a purely cinematic perspective (it was shot by long-celebrated cinematographer Gregg Toland) it would be interesting to at least look at an HD version. The blending of animated and live action was fairly advanced for its time, or so I’ve always understood. It would be interesting to give it a looksee for the technique aspect alone. Ironically, of course.

I don’t know if Disney + management has even considered such a move (highly doubtful — the movie is obviously bad news and bad nostalgia from a present-day perspective) but among the hundreds of titles that will be streamable on the new channel, it would be brave of them to offer it.

Wiki history: “Song of the South was re-released in theaters several times after its initial 1946 premiere, each time through Buena Vista Pictures: in 1956 for the 10th anniversary; in 1972 for the 50th anniversary of Walt Disney Productions; in 1973 as the second half of a double bill with The Aristocats; in 1980 for the 100th anniversary of Joel Chandler Harris’ classic stories; and in 1986 for the film’s own 40th anniversary and in promotion of the upcoming Splash Mountain attraction at Disneyland and Disney World.

“The entire uncut film has been broadcast on various European and Asian television channels including by the BBC as recently as 2006. The film (minus the infamous Tar Baby scene which was cut from all American television airings) was also aired on U.S. television as part of the Disney Channel’s ‘Lunch Box’ program in the 1980s and 1990s until December 18, 2001.”

Herman Melville naturally couldn’t have known when he created Starbuck, the 30-year-old chief mate of the Pequod, a thoughtful and intellectual Quaker from Nantucket, that he was, after a fashion, helping to launch a hugely successful coffee empire that wouldn’t be copyrighted until 120 years after the publishing of “Moby-Dick“…imagine.

How’s that for a long, clause-dependent opening sentence?

Seriously: I’ve been fascinated all my life by the faded, almost monochromatic color scheme used for John Huston‘s Moby Dick (’56) and co-created by dp Oswald Morris — subdued grayish sepia tones mixed with a steely black-and-white flavoring.

This special process wasn’t created in the negative but in the release prints, and only those who caught the original run of the film in first-run theatres saw the precise intended look.

There’s a new Region B Bluray of Huston’s film being issued by Studio Canal on 11.11, which will probably look like the 2016 Twilight Time Bluray, which features restoration work by Greg Kimble. The same featurette about the color process that was on the ’16 Bluray, “A Bleached Whale — Recreating the Unique Colour of Moby Dick,” will also be on the Studio Canal version.

https://hollywood-elsewhere.com/2016/12/not-real-mccoy-good-can-hoped/

Posted 4 and 2/3 years ago, on 4.1.15: Alex Gibney‘s All Or Nothing At All (HBO, 4.5 and 4.6), the two-part, four-hour doc on Frank Sinatra, is an intimate saga of an artist with a profound vocal gift, a legendary sense of style, a swaggering ego, an open heart when it came to friends and family, a lust for the ladies, a chip on his shoulder and a street attitude that led to certain feelings of kinship and camaraderie with mob guys.

It’s quite the loving valentine, and it makes you feel like you’re in Sinatra’s home corner every step of the way, and in this sense it’s unique — there’s never been this much love and understanding shown to Sinatra and his legend from a polished, first-class doc by a world-renowned director. It’s Gibney’s trick, of course, to make you feel that you’re not being egregiously lied to. Which of course the doc is definitely doing by omission.

What matters is that Gibney’s accumulation of lies are, at day’s end, artful. Because the doc is filled with bedrock emotional truths and echoes.

And you can’t beat the first 56 years of Sinatra’s life (’15 to ’71) for sheer emotion, Shakesperean drama, urban pizazz, ups and downs, top-of-the-world success and down-in-the-gutter career blues…a saga of an all-American, knock-around life that spanned most of the 20th Century, and one that became less and less interesting when Sinatra turned smug and gray and more-or-less Republican in the late ’60s until his death on 5.14.98 at age 82.

I was quite moved and charmed by much of it, but this is a family-approved doc that’s basically about re-igniting commercial interest in Sinatra product (CDs, films) by way of celebrating his 100th birthday, which is actually not until 12.12.15. That means it’s really friendly…a doc that is always looking to show love and understanding or at least muted affection…a highly skillful handjob as far as classy, high-end biopics go. No judgment, no impartiality…every well-known or rumored-about negative in Sinatra’s bio is finessed or explained away in some first-hand, no-big-deal fashion by Sinatra himself or by a friend, or otherwise brushed off.

In no way, shape or form does Gibney’s doc approach the tone or the attitude or the sometimes cutting observations in Gay Talese‘s “Frank Sinatra Has A Cold,” a landmark 1966 profile of the then 51-year-old singer at a vaguely downish stage in his life.

And in no way does Gibney’s doc try to get into a thumbnail view of Sinatra that author Nick Tosches ascribed to Dean Martin — “A half a mozzarella who never grew up.” All or Nothing At All is about kind, understanding thoughts and contemplations. I wouldn’t even call it “forgiving” because accusations are really never heard. But it’s quite skillful and heartening and…what, calming? Gentle, intimate, stirring…always a sense of Sinatra’s sadness and vulnerability. I’m actually thinking of watching Part One all over again.

Not to take anything away from the currently third-ranked Scarlett Johansson, who plays Adam Driver‘s estranged actress wife in Marriage Story, but after Sunday’s screening of Bombshell I’m feeling a bit more enthusiasm for Charlize Theron‘s performance as embattled Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly, especially considering the first-rate facial re-shaping and chin-sharpening that allows Theron to closely resemble the Real McCoy. I’m not persuaded that Theron has rocketed into the top slot and thereby shoved aside Judy‘s Renee Zellweger, but she’s definitely parachuted into the race with appropriate fanfare.

Two months ago or in mid-August, I earnestly praised Boon Joon-ho‘s Parasite to a certain degree. But also with some reservations. Critics had been gushing over the Palme d’Or winner since it premiered last May in Cannes, but now that it’s open and playing in the U.S. I’d like to engage in a debate about the plusses and minuses.

Please understand that portions of the remainder of this column will contain spoilers.

In an 8.14.19 piece called “Least Problematic Bong Joon-ho,” I wrote that I’d seen four of his films — The Host (’06), Mother (’09), Snowpiercer (’13) and Okja (’17). And that my reactions were the same all along — I admired the craft and energy, didn’t believe the stories. To me it seemed obvious that Bong was more into high impact movie-ness than establishing at least a tenuous relationship between his scenarios and the terms and conditions of real life.

The darkly humorous Parasite “is different,” I noted. “For the first time Bong allows you to half-invest in the story (co-written by himself and Han Jin-won), which offers a witty, satiric portrait of South Korea’s haves and have-nots. Up to a point (or during the first 30 to 40 minutes), the world of Parasite actually resembles the way things are, or at least could be. But it still feels more movie-ish than persuasive.”

I have five beefs with Parasite. The film’s defenders need to explain how I’m wrong or mistaken…thanks. Let the arguments commence.

(1) It makes no sense at all that a poor family of four could successfully deceive and manipulate a rich family into hiring them all in different positions, and expect that the rich family would never sniff a conspiracy. Sooner or later the rich employers would smell it. Especially with the snooty paterfamilias (“Mr. Park”, played by Lee Sun-kyun) noting at one point that the poor father Kim Kitaek (Song Kang-ho) has an aroma very much like their recently hired housekeeper (and Kim’s wife), Kim Chung-sook (Jang Hye-jin). All they have to do to eliminate that notion is take extra-long showers with different brands of body-gel soap.

(2) It makes no sense that this family, sitting in their absent employer’s home and eating fine food and getting drunk, would allow the recently fired former maid, Moon-kwang (Lee Jung-eun), who has every motive in the world to expose the poor family’s deceptions, into the home. But they do so anyway. Worse, when they’re drunk and dishevelled. Which is absurd.

I’ve only just seen the ultra-violent, pro-Trump, anti-media and anti-liberal video that was assembled by a person (or persons) who attended a gathering thrown by a loony right organization, American Priority, and shown last weekend at the Trump National Doral Miami as part of a conference of Trump supporters, titled AMPFest19.

The video, which has a degraded, third- or fourth-generation digital texture, is a rightwing slaughter fantasy, rancid and hateful and brimming over with rage. However unfortunate, it’s yet another, fully consistent expression of the sentiments of the media-and-liberal-hating hinterland Trump faithful, a small number of whom, of course, have been behind racially-motivated shootings.

Borrowed from an actual church massacre scene from Matthew Vaughn‘s Kingsmen: The Secret Service, it shows a crudely digitized Donald Trump shooting, bashing and stabbing various news media reps as well as Hillary Clinton, former President Obama, Bernie Sanders (whose white hair is lit on fire), Sen. Mitt Romney, Morning Joe co-host Mika Brzezinski, Rosie O’Donnell and Rep. Maxine Waters.

White House press secretary Stephanie Grisham tweeted today that while President Trump has not seen the video, “based upon everything he has heard, he strongly condemns” it. An American Priority statement on its website says that “it has come to our attention that an unauthorized video was shown in a side room at #AMPFest19…the video was not approved, seen or sanctioned by the AMPFest19 organizers.”

Asked during a May 1999 Good Morning America interview whether sobriety had changed him, George C. Scott said, “The only reason I’m sober is because I didn’t want to die. And that’s why. Otherwise I had a good time drinking. I drank for 40 years, and I [did] my best at it and loved every minute of it. Except when I was throwing up. But you get into bad scrapes, etc. Too many ruptured relationships and all of that. And it’s a bad scene.”

Scott was only 71 at the time, but he looked older and certainly worse for wear. Four and half months later he died of a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, no doubt brought on by all those decades of drinking as well as smoking, which Scott was doing during the interview.

I was honored to chat with Scott on the set of William Freidkin‘s remake of Twelve Angry Men (’97). He had the Lee J. Cobb role (juror #3). A sharp mind, lion-like energy, fun to kick it around with. The publicist insisted on sitting in on all discussions but whatever. Jack Lemmon played Henry Fonda‘s role (juror #8) in that production, and I was sitting next to Scott as we watched Lemmon and a few others rehearse a scene. When Lemmon bungled a line, Scott leaned back in his chair, exasperated and muttering, “Jesus, Jackie…”

Scott was right about a drinking life being highly enjoyable except for the downside aspects — it can be. I was never into any hard stuff until the early ’90s, which I began to succumb to vodka and lemonade as a 9 pm reward for a long day’s labor. Otherwise I loved raising a nice glass of wine at dinner or afterwards. Paris and Rome are extra-wonderful places if you’re imbibing.

That said, my seven and a half years of sobriety have been blessed, all things considered. The clarity of mind and soul, the feeling of orderly well-being, etc. As much as I loved sipping the vino, there’s a part of me that wishes I’d embraced sobriety 15 or 20 years earlier.

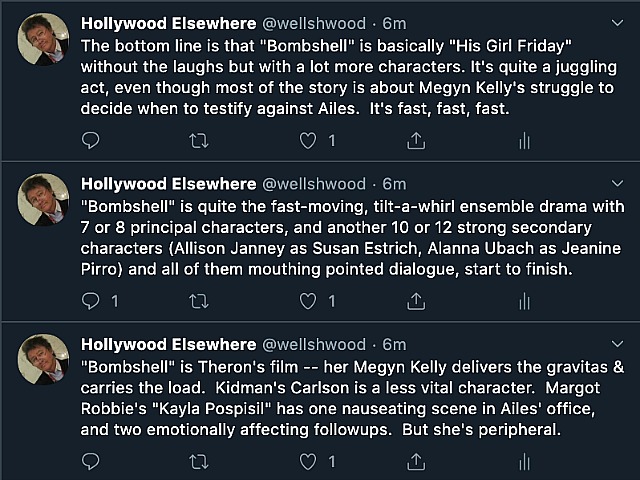

I saw Jay Roach and Charles Randolph‘s Bombshell (Lionsgate, 12.20) at a 2 pm screening at Westwood’s Bruin theatre. I had to wait until 9 pm to tweet my reactions.

Vaclav Marhoul‘s The Painted Bird (IFC Films, sometime in early 2020) probably won’t win the Best Foreign Language Feature Oscar, but, as the official Czech Republic submission, it totally deserves to be nominated. Because within its own ravishing and diseased realm, it’s a great film. It just happens to be tough to sit through.

I saw it last night and holy moley holy fucktard. It’s about a little Jewish kid (Petr Kotlár) trying to survive all on his own in eastern Europe during World War II, and man, does he suffer the drawn-out pains of hell. So did I in a manner of speaking. But not altogether.

I’m calling The Painted Bird a “beautiful” highbrow art film for elite critics and cineastes who have the fence-straddling ability to enjoy magnificent b&w cinematography (all hail dp Vladimir Smutny) and austere visual compositions while savoring the utmost in human cruelty and heartless perversion.

The vile, animal-like behavior is unrelenting; ditto the highly sophisticated monochrome arthouse chops. Marhoul is quite gifted, quite determined and uncompromised, and quite the bold cinematic artist. He is also, as Kosinski was, one sick fuck.

I mean that in a good way as Marhoul is a Bergman-like in an unrelenting clinical way; he never panders or tries to soften things up for the mom-and-pop schmuckos — he’s totally playing to Guy Lodge and his ilk. This is a movie about some awful, horrific, beastly people (Harvey Keitel‘s priest and the kid’s father excepted), and what agony it can be to suffer under them on a prolonged basis.

I read Kosinski’s “The Painted Bird” when I was 22 or 23, and I somehow absorbed all the horrific sadism and cruelty and lonely agony without incident because of the dry, matter-of-fact Kosinski prose. It’s quite another thing to hang with that feral, dark-eyed little kid who doesn’t talk for the entire film.

What is the perverse obsession with people and animals being hung upside down by ropes? What was so terrible about servicing that hot-to-trot farmer’s daughter (Jitka Cadek Cvancarova)?

The instant you see white-haired, beard-stubbled Udo Kier, you go “oh God, here comes another cold, maniacal, salivating monster performance.” Harvey Keitel is totally subservient to the mise en scene — just playing an old, white-haired priest who coughs a lot and then dies. Julian Sands plays a total salivating beast. Barry Pepper (who was young 20 years ago but no longer) is interesting as a Russian soldier with no love for Communism or Josef Stalin.

Exquisitely made, and utterly hellish to the core in terms of its depiction of the human condition. I happen to be on friendly terms with one of the producers, Tatiana Detlofson, who used to be married to Variety‘s Steven Gaydos. Does it deserve to be nominated for Best Foreign Language Film? Yes — it’s too well made not to be so honored. Every frame screams “soul-cancer arthouse perversion“.

Originally posted on 7.25.11: The gist of Scott Feinberg‘s 7.25 piece (“The Art of Dying Young‘) about the death of Amy Winehouse is that it’s not such a terrible thing to check out early if your legend is going downhill anyway. Biological shutdowns will always be traumatic to friends, fans and loved ones, but it’s arguably worse, Feinberg is saying, to hang on past your peak point.

But how do you know when you’ve peaked? Answer: Nobody ever does. Everyone goes through life saying, “I’ll find a way to turn things around…after all, tomorrow is another day.”

“Most [performing survivors] overstay their welcome,” says Feinberg, “and simply begin to evaporate from the public’s consciousness, either because they find themselves (a) unable to maintain the performance-level that first garnered them fame, (b) creatively limited by the public’s limited perception of them, (c) distracted and/or deterred by fame and its trappings, (d) no longer able or willing to compete with ‘fresher’ faces.”

Truman Capote certainly fell prey to (c). I remember to this day what Gore Vidal said when Capote more or less committed suicide: “A very wise career move.”

If I could re-orchestrate my life from a free-for-all cosmic perspective, I’d like to live about 250 years but get no older than, say, 42 years. I’d arrange to be born in 1800 with my current consciousness intact, and then explore the unsullied American frontier and become an inventor and buy up all the patents for everything and become stinking rich.

And then tour the world and become friends with everyone worth knowing — young Abe Lincoln, Leo Tolstoy, Chief Sitting Bull, Herman Melville, young Katherine Hepburn, Frederick C. Douglas, Karl Marx, Charles Dickens, Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., Isadora Duncan, D.W. Griffith, Theodore Roosevelt, John Reed, Jack London, young Cary Grant, young JFK, young John Lennon, etc. And then wind things down around 2050, give or take. Or maybe keep going.

All though the decades I’ve had a problem with the spelling of this famous character’s name — it should obviously have two “o”s (as in the spelling of Jimmy Doolittle, commander of the 1942 air raid upon Japan) and not just one. You can’t have that “ooooh” sound without two “o”s. One “o” produces an “oh” sound, as in dough.

Dolittle, God help us, will open on 1.17.20. Costarring Antonio Banderas, Michael Sheen, Jim Broadbent; Malek aside, the voice cast includes John Cena, Marion Cotillard, Carmen Ejogo, Ralph Fiennes, Selena Gomez, Tom Holland, Kumail Nanjiani, Craig Robinson, Octavia Spencer, Emma Thompson and Frances de la Tour.