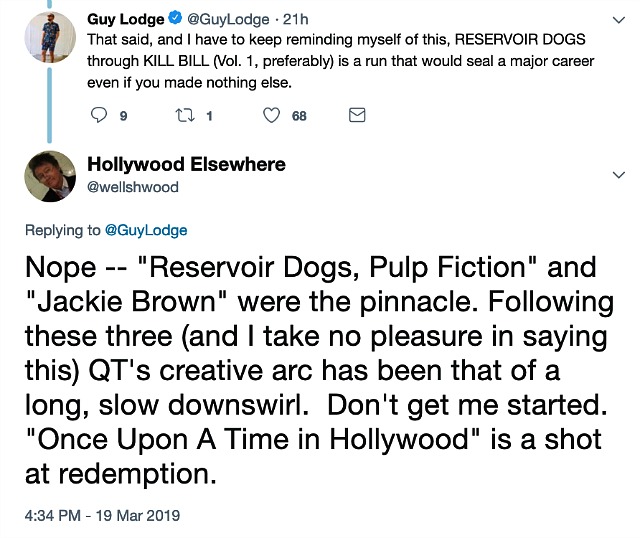

We now know that Quentin Tarantino‘s Once Upon A Time in Hollywood is locked for Cannes ’19, and that Dexter Fletcher’s Rocketman will almost certainly appear there also.

And now Variety‘s Cannes ’19 prediction piece (written by Peter Debruge and Elsa Keslassy, and co-reported by John Hopewell, Nick Vivarelli, Patrick Frater, Leo Barraclough and Richard Kuipers) assures that Benedict Andrews‘ Against All Enemies, a drama about the FBI’s ghastly persecution of poor Jean Seberg from the late ’60s and into the ’70s, is more or less firmed.

Pic stars Kristen Stewart as Seberg, and costars Jack O’Connell, Anthony Mackie, Vince Vaughn, Margaret Qualley, Zazie Beetz, Stephen Root and Colm Meaney.

A March ’17 draft of Joe Shrapnel and Anna Waterhouse‘s script, titled Seberg, ends well before Seberg’s 1978 Paris suicide, when she was 40. The final scene in the script is about Seberg learning from a sympathetic FBI guy (Jack O’Connell) about a fictitious FBI allegation that the father of a baby girl born to Seberg on 8.23.70 (and who died two days later) was Black Panther activist Raymond Hewitt.

Seberg was nonetheless romantically linked with another Black Panther member, Hakim Jamal (played in the film by Anthony Mackie).

From Seberg’s Wikipage: “In 1970 the FBI circulated a false story that the child Seberg was carrying was not fathered by her husband Romain Gary but by Raymond Hewitt, a member of the Black Panther Party. The story was reported by gossip columnist Joyce Haber of the Los Angeles Times, and was also printed by Newsweek magazine.

“Seberg went into premature labor and, on August 23, 1970, gave birth to a 4 lb (1.8 kg) baby girl. The child died two days later. She held a funeral in her hometown with an open casket that allowed reporters to see the infant’s white skin, which disproved the rumors.

Read more