Daily

The Day I Broke Through

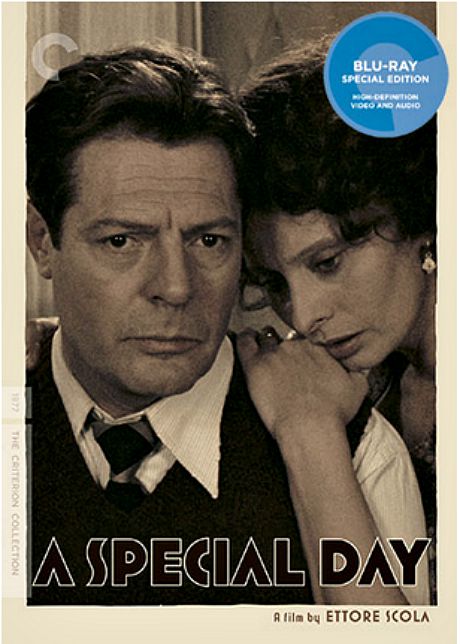

I used to struggle with film reviews when I first began in this racket back in the late ’70s. I was so intimidated by the great critics of the day (Sarris, Kael, Simon, Canby, Denby, Corliss, et. al.) and so desperate to sound cool that I could barely make a paragraph work after an hour’s toil, and a whole review would take four or five hours and sometimes a whole day. I couldn’t relax or breathe, kept rewriting myself into a stupor. And then one day the clouds parted. I wrote a review of Ettore Scola‘s A Special Day and for the first time, it just flowed right out. I rewrote and refined, of course, but the initial writing was much less tortured than usual. So I’ve always felt a special kinship with this 1977 film (which was actually released in the States in ’78, if I’m not mistaken). And so I’m definitely going to beg Criterion’s p.r. company for a freebie of the upcoming Bluray (due on 10.13).

Tedious American Puritanism

A rising politician indulging in sexy escorts is not an expression of his dark side — it’s a symbol of his private side. The only person who needed to be seriously concerned about John F. Kennedy‘s catting around was Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, and it’s been abundantly proven that his sexual escapades never once got in the way of his Oval Office duties or decisions. (On the other hand texting photos of your bulging manhood to an extra-marital interest is proof of idiocy and/or self-destructiveness.) And by the way, I love the fact that Ray Winstone is playing a crafty investigative journalist. Hollywood hasn’t let him play anything other than goons and thugs for the last 20-odd years.

Southpaw Isn’t Good Enough, Gyllenhaal Goes Pure Simian

I saw Southpaw a week ago Monday, down at L.A. Live on 7.13, and the best part of the whole experience was eating the popcorn when it was still warmish and buttery and salted. Otherwise I just sank into my seat and toughed it out. It’s been a while since I disliked a lead character as much as Jake Gyllenhaal‘s Billy Hope, who’s basically an amalgam of physical and behavioral boxer traits from other movies turned up to 11 — Jake La Motta‘s tenacious, bore-right-in combativeness, Terry Malloy‘s wounded face (enhanced here with the swellings and cuts and the old watery blood eye) plus the emotional wallow of Sylvester Stallone‘s Rocky with an extra-heavy helping of simian sauce (punchy speech, emotionally primitive, no diction to speak of, barely literate).

On top of which Hope, a light heavyweight champ, spends money like a drunken sailor and lives in an ostentatious McMansion that almost made me physically sick. The guy’s an absolute mutt. I was sitting there going “I’m stuck with this knuckle-dragger for the next two hours?”

And you’re telling me that Rachel McAdams‘ Maureen, who relates to Hope because they both had tough Hell’s Kitchen childhoods, is his loyal wife? No way. She’s way too good for him. And then something awful happens and the pillars of Hope’s life start tumbling and crashing and before you know it he’s down and out with nowhere to go but up. If, that is, he can suck it in and learn from his mistakes and listen to advice from his humble but wisely paternal trainer, played by Forest Whitaker in a Clint Eastwood-in-Million Dollar Baby mode, about how to start boxing wisely and not get hit so much and so on. Hey, maybe Billy can go to a community college and learn how to speak like an educated eleven year old!

And then Billy’s ex-manager, played by by 50 Cent, arranges for a big, career-restoring championship fight with the arrogant young buck who…you don’t want to know. I didn’t want to know when I was watching it. I wanted to bolt but I had to stay. Because I’m a pro and I ride it out.

“Some Guys Just Can’t Catch A Break”

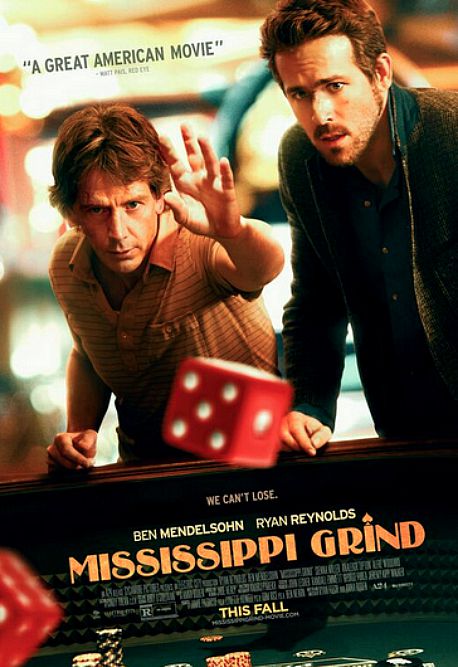

You look into the face of Ryan Reynolds and you say, “I like this guy…I want him to win or at least come out okay…give me a chance and I might even admire him.” You look into the face of Ben Mendelsohn and you say, “This guy sweats too much…he might be winning tonight but he’ll definitely lose tomorrow, and he won’t stop smoking those Marlboros…drop him off at the nearest bus stop.” And yet — I’m being serious here — Mississippi Grind (A24, 9.25) is a really well-made film. I knew that right away when I saw it at Sundance. It’s worth seeing, even with Mendelsohn’s b.o. filling up the room.

“Years Go Falling In The Fading Light”

42 days ago I asked “what would we lose as a community or a culture if a final, irrevocable pledge was made by producers Michael Wilson and Barbara Broccoli to never make another 007 film again, to just walk away and leave it forever?” My answer was “nothing” but the reader response was “everything! We wants our 007…don’t take him away….noooo!” Listen to me: I am sick to death of this franchise detonating explosions around the world. Spectre filmed in Italy, Austria, Morocco and Mexico, and you can be assured that big bluhdooms, the sound of squealing tires and clink of Martini glasses will be heard in each one of them. I’m numb; the novocaine is spreading. There is so much that could be conjured in the way of danger, thrills and suspense, and all the Bond films know how to do is press “autopilot.”

When The Heat Is Upon You

I’ve noted a few times that Ryan Fleck and Anna Boden‘s Mississippi Grind (A24, 9.25), which I caught at last January’s Sundance Film Festival, is essentially a revisiting of Robert Altman‘s California Split (’74). Okay, not a precise remake but close enough to one. It’s certainly one of the more enjoyable addiction films I’ve ever sat through. It has an assured, nicely textured, low-key ’70s quality, and is easily the best film that Ryan Reynolds, whose performance as a good-natured knockabout (i.e., the Elliot Gould role) is completely centered and confident, has ever starred in. No, that’s not damnation with faint praise. I was even okay with the frequently annoying Ben Mendelsohn, who plays a somewhat glummer version of the George Segal role in the ’74 original. And I enjoyed James Toback‘s snarly cameo as a guy with a hard fist. Will Joe Popcorn decide that Grind is a little too downbeat and meditative? Maybe, but for anyone with a half a brain it definitely intoxicates and charms for much of its running time. Wow…I just realized I can’t remember how it ends.

Son of Chrome-Plated Nazi Helmet

Eons ago some friends of mine had to deal with a second-rate motorcyle-gang psychopath who went by the name of Wild Bill. It happened in a small apartment that three of us — Chance, Mike and myself — were staying in next to a performance bar called Fat City in Wilmington, Vermont. I was luckily passed out in the bedroom from an overdose of Jack Daniels, but Chance’s descriptions have never left me.

It began with a loud knock on the door and Chance saying “who is it?” and a voice saying “look though the peephole.” (One of those dime-sized holes with a tiny metal latch.) Chance started to put his eye to the door when a switchblade knife blade suddenly jabbed through a couple of times. Chance got angry and opened the door and there was Wild Bill, wearing a chrome-plated Nazi helmet. He muscled his way in and wouldn’t leave.

He was fried and stupid and clearly dangerous, Chance said. Not what you’d call a top-of-the-line biker but a loser type. Bill had a pair of pliers hanging from his belt, and Chance asked him what they were for. “I’m an amateur dentist,” he said.

You could feel the booze and boiling rage, Chance said. Telling Bill to leave or (ha!) trying to force him out would’ve surely resulted in aggravated assault or worse. Chance and Mike decided to humor him.

“You Know Any Right-Wing Folk Songs?”

Here’s to Theodore Bikel, a burly Austrian-Jewish character actor with a large heart and probing mind. By my criteria he nailed it in at least two films — as a World War I-era German Naval lieutenant in John Huston‘s The African Queen (’51), and as a laid-back, good old boy Sheriff chasin’ after Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier in Stanley Kramer‘s The Defiant Ones (’58). I never met him but Bikel was a fellow Wiltonian who used to have a sizable place on Honey Hill Road. An earthy fellow, good humored, married four times. He passed yesterday at age 91.

Bikel started out as an actor but then got into the ethnic folk music thing in the’50s, and he was right there at the ’65 Newport Folk Festival when Dylan went electric [see video above]. In folk music circles Bikel was regarded as an old guard lefty and even a bit of a conservative by mid’ 60s standards…union guy, the “Wobblies“, a baggy-pants roustabout, part of the Alan Lomax realm. But he and Peter Yarrow were cool with Dylan after the booing started, both suggesting that he go back out and do an acoustic set. (And he did.)

“Do You Like Your Life?”

Judd Apatow‘s Bill Cosby impression runs from 2:35 to 3:55. ‘Nuff said.

What’s The Upside?

Why did Jesse Eisenberg and Kristen Stewart agree to costar in an obviously low-rent, less-than-inspired exploitation film that borrows from the old Long Kiss Goodnight and Bourne Identity formula (i.e., trained government agent with apparent amnesia, living in relative obscurity, suddenly having to evade attempts by agency to kill him)? Did they need the money or something? A film like this lowers the value of their respective brands and that’s all. With admired performances in Camp X-Ray, Clouds of Sils Maria and Still Alice, Stewart has finally established herself as a formidable thesp…and now she’s plotzing. Eisenberg has already made a few brazenly commercial flicks (Now You See Me, the forthcoming Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice) and is committed to Now You See Me: The Second Act. Plus he’s been expanding upon his sensitive-OCD-guy chops with The End of the Tour and Louder Than Bombs. I understand acting in semi-cool commercial flicks like Adventureland and Zombieland but not something like this, which is obviously shit.

When Panthers Stirred The Pot

From John DeFore‘s 1.23.15 Hollywood Reporter review: “A strong if only occasionally transporting biography of a movement that terrified the establishment in its day, Stanley Nelson’s The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution (PBS Distribution, 9.2 in NYC) speaks to many former members of the Black Panther Party about what its breed of revolutionary activism felt like at the time. Straight history is not the whole point here, as Nelson enthusiastically conjures a sense of what it felt like to be a Panther and to be a young black person inspired by them.”

Felicia and Leonard Bernstein and their guest of honor, Black Panther “field marshal” Donald Cox, during a fundraiser held at Bernstein’s Park Ave. apartment. The event was famously written about in Tom Wolfe’s “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s.”

The film does not overlook various examples of “present-day relevance,” DeFore notes.

“We’re introduced to the young Huey P. Newton, who realized that it was legal to carry loaded guns in public and understood that doing so in the vicinity of police interacting with Oakland’s black population would draw more attention to racial justice issues than a million printed fliers. He and Bobby Seale organized the party, which began with a focus on militancy but soon launched major charitable programs, including a famous free-breakfast effort that fed children 20,000 meals a week.

“While he shows the power of the ‘Free Huey’ slogan, Nelson isn’t eager to investigate it; he tells us almost nothing about the incident that led to Newton’s imprisonment (he was accused of killing a policeman), nor does he give us any way of guessing whether it was just or unjust.