This is obviously…okay, seemingly of a very high order. Maybe. If your idea of “a very high order” is a mixture of Runaway Train, the “political exiles on a long ride to the Urals in a cattle car” sequence from Dr. Zhivago (which incidentally contains my beloved “I am the only free man on this train!” scene with Klaus Kinski) and the “realistic” CG panache of Robert Zemeckis‘s Polar Express. I’m also figuring you can’t go wrong with Tilda Swinton in a scenery-chewing mode

Daily

What Happened Was

I don’t know what crawled up the ass of the Parisian Weather Gods but the air was like mid-November when I stepped out of Charles DeGaulle airport this morning around 8:30 am. Not to mention the gusty breezes…how much would it cost to buy a winter overcoat? Not to mention the misty moisture that wasn’t quite rain but was close enough. Not cool, not welcome. Where the hell is global warming when you really need it? Took the good old Roissy bus into town. My Airb&b sublet in the 17th wouldn’t be ready until 1 pm so my landlady let me drop my bags off at her place. Enjoyed a nice omelette and two cafe noirs at a Montmartre cafe but the wifi (boldly promoted on a sign outside this humble establishment) was on the fritz. It wasn’t exactly cost-efficient to buy a scarf but I was chilly and uncomfortable so I got one. The sublet is in a downmarket area of the 17th (near the La Fourche metro stop) but it’s not too bad. The place itself is terrific — quaint, cozy, homey. The Godzilla screening at the Rex starts in a couple of hours. I guess I’ll just come back here to write the review.

Theological Discussion

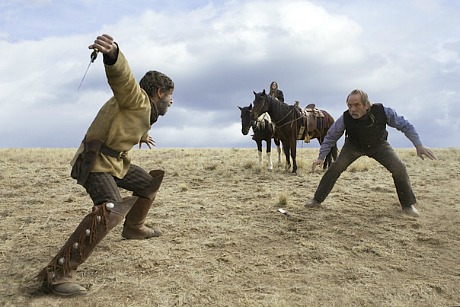

I’m telling you right now that between the nihilistic muttering and his occasionally challenging if not indecipherable strine accent I’m not going to understand half of what Guy Pearce is saying in David Michod‘s The Rover. I’m telling you this right now. During the Cannes screening I’m going to be cupping my ears, leaning forward in my seat…the whole schpiel.

Action Revolution Killing Oratory Fantasy Fornication

A Vanity Fair Film Snob video piece about the faithful-custodian theology of Roger Corman, Samuel Arkoff and American International Pictures. “A.I.P.: commonly used abbreviation for American International Pictures, a crank-’em-out production company founded in 1954 that has since come to be revered by Film Snobs as a font of important kitsch.” One could argue that the foundation of Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez‘s 21st Century careers have been about tributes to AIP exploitation fare.

Fast Friday

It’s now 11:45 am. I have to leave for JFK at 3 pm or thereabouts. The Delta flight to Paris leaves at 6:02 pm, arrives at 6:46 am Saturday morning.

Union Square — Thursday, 5.8, 2:10 pm.

The cold-water knob in the shower where I’m staying is infuriating — just a slight turn to the right and the water is scalding, and a slight twist to the left turns the water cool-ish. Finding a happy in-between is a struggle.

Easy Rider

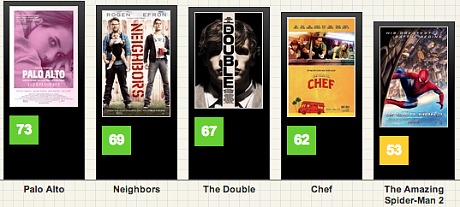

Today’s distinctive openers are Jon Favreau‘s Chef, Nicholas Stoller‘s Neighbors and Gia Coppola‘s Palo Alto. Favreau’s film is a feel-good concoction, but it’s far and away the most engaging of the three — the liveliest, best-written and most personable. On top of which the food is constantly sensual if not erotic. Yes, the under-subject (leaving aside the road-to-redemption arc of Favreau’s lead character) is social-media humiliation and promotion — an aspect that works as far as it goes (even if it the ease and speed of the film’s up-and-down cyber scenarios seem a little too facile). But it never delivers an uncomfortable moment. In a left-field sort of way Chef reminded me of Fred Zinneman‘s The Sundowners (’60) in that it charmingly ambles along without a lot of difficulty — nothing all that traumatic or devastating happens to anyone, and after a while you start to enjoy this sense of comfort.

Rosey Colors, A Palette Less Gaudy

Vertice Cine has issued an all-region Bluray of John Huston‘s Moulin Rouge (’52). Which is necessary viewing, I feel, for the subdued, somewhat hazy, rosey-toned color scheme created by Huston and dp Oswald Morris, who passed a few weeks ago. From the Wiki page: “Huston asked Morris to render the color scheme of the film to look ‘as if Toulouse-Lautrec had directed it’…Moulin Rouge was shot in three-strip Technicolor, [but] Huston asked Technicolor for a subdued palette, rather than the sometimes gaudy colors that ‘glorious Technicolor’ was famous for. Technicolor was reportedly reluctant to do this.” Moulin Rouge received seven Academy Award nominations and won two (art direction, costume design), and yet Morris’ cinematography was bypassed.

Cannes Usual-Usuals

The Hitfix Cannes guys (Gregory Ellwood, Guy Lodge, Drew McWeeny…wait, Ellwood is attending this year?) have listed and summarized 12 films that are on almost every high-priority list of every Cannes-attending journo-schmourno: Bennett Miller‘s Foxcatcher (the top of my list), Nuri Bilge Ceylan‘s Winter Sleep (a close second), Mike Leigh‘s Mr. Turner, Tommy Lee Jones‘ The Homesman, David Cronenberg‘s Maps to the Stars, David Michod‘s The Rover, Gabe Polsky‘s Red Army (co-lensed by HE pally Svetlana Cvetko), Olivier Assayas‘ Clouds of Sils Maria (mopey movie-industry women hanging out in a small Swiss town), Jean-Luc Godard‘s Adieu Au Langage (who outside of Godard-ophiles would be even half-interested in this if not for the 3D photography?), Ryan Gosling‘s “experimental” (read: probably somewhat dicey) Lost River, Asia Argento Incompresa (not on my list, pally) and Atom Egoyan‘s The Captive (nope). And yet they’ve left off Michel Hazanavicius‘s The Search, which could turn out to be one of the more distinctive and penetrating dramas of the lot. (Lodge ran a separate piece about it, but including Incompresa or The Captive at the expense of The Search seems…well, perverse.) And they totally overlooked Abel Ferrara‘s Welcome to New York. The festival (which kicks off five days hence, or four days if you count the annual La Pizza gathering as the kickoff event) still seems to me like the most underwhelming, Cote d’Azur-centric, self-regarding, not-necessarily-trailblazing-in-a-commercial-or-awards-context roster in a long, long time.

Ferenice Bejo, Maksim Emelyanov in Michel Hazanavicius’s The Search.

From Tommy Lee Jones’ The Homesman.

Another World

Earlier today entertainment reporter, stand-up comedian and advertising exec Bill McCuddy persuaded me to visit Bergdorf Goodman and buy a nice tube of Supersmile toothpaste ($25), which is supposed to be a good whitener. I also popped for a Supersmile toothbrush ($15). I then walked over to the Bergdorf Goodman men’s store just to mosey around. I saw an attractive scarf and asked a salesman for the price. In a normal store a really cool scarf would cost $75 so I figured the BG price would be $225. The salesman looked at the tag, looked me in the eye and told me the price: $725.

Satisfaction

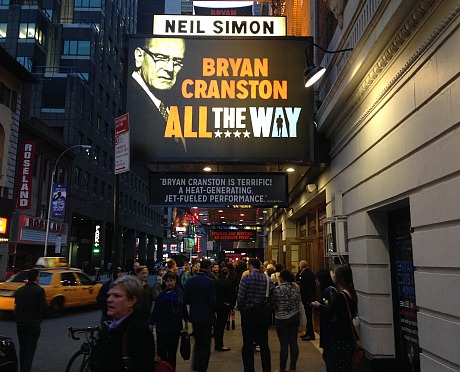

In Robert Schenkkan’s stirring but somewhat limiting All The Way, which I saw last night, Bryan Cranston captures the cagey manipulation and animal spirit of Lyndon Baines Johnson without really sounding like him or even adopting the drawly laid-back accent that the 36th President used. But he’s a locomotive, all right — a ball of spit, piss, gravel and fire. All my life I’ve thought of Johnson’s five-year presidency as tragic — the big man who had it all and then lost it all. The play ignores all that in order to focus on LBJ’s more-or-less triumphant phase from November ’63 to November ’64 when he calmed the nation in the wake of JFK’s murder, managed to push through the 1964 Civil Rights Act and then was elected President by a landslide. Honestly? I felt engaged but not enthralled. Respect and interest start to finish, and delight and amusement from time to time. But I wasn’t emotionally engulfed. And yet it’s an expertly written ensemble piece and a crackling political drama. Good enough, money well spent, not worth going after.

Big Baby Pulls Plug on Hissy-Fit Lawsuit

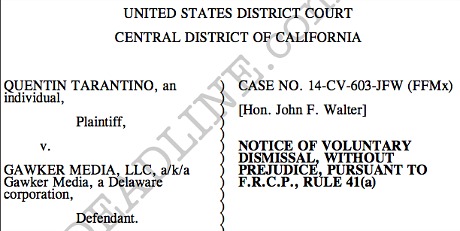

Quentin Tarantino‘s Hateful Eight copyright infringement script-leak lawsuit against Gawker has always seemed primarily emotional in nature. By that I mean entitled and tantrum-y. Now, a week after amending his original complaint, he’s done another spoiled-child mood swing and more or less dropped the lawsuit altogether. What a fucking child, what a wuss…a big, pot-bellied, ego-strutting enfant terrible who’s bored and wants to move on to something else.

While Rome Burns…

In the wake of a new U.S. government climate change study, a 5.6 N.Y. Times article by former Utah governor Jon Huntsman quoted a Pew poll that said 41 percent of Tea Party Republicans believe “that global warming was not happening” and that “another 28 percent said not enough was known.” A related Times article by Megan Thee-Brenan reported that Americans are generally the most denial-prone among all the industrialized nations regarding climate change. At what point should climate-change deniers and disputers stop getting a pass? 10 or 15 years hence if not sooner they’ll be gone from news-channel discussion panels. Their views will be deemed so absurd as to not even merit passing consideration.

The more pernicious and threatening this situation gets, the less radical my green reeducation camps idea will seem. If you don’t want any kind of future for your grandchildren and great-grandchildren, fine…let’s just cruise along and do nothing. But there’s really no way to argue against the notion that rural yokels and their Congressional reps are, no exaggeration, the most malicious villains of our time. Public enemies in every conceivable sense of that term. I explained it all in an 8.5.09 piece called “Argument Over Beers.”