Daily

Trans-Atlantic Wifi

I’m tapping this out from seat 36D on my American Airlines flight from Heathrow to LAX. That’s right — it’s a Boeing 777-300ER with international effing wifi. $19 bucks for the whole flight. Not the fastest but a blessing all the same. Plus an electrical outlet for each seat. Limited availability now — JFK to Heathrow, Miami to Heathrow, Dallas/Fort Worth to Hong Kong, Miami to Sau Paulo. I’m flying American from here on whenever I go to Europe. Today’s flight left London at 2pm GMT. It’s now 10:45 GMT or 2:45 Pacific. The LAX landing should happen around 4:45 pm.

In This Order

HE’s Best Films of 2013 (features and docs, merit alone, in this order, forget award season for now): 1. Steve McQueen‘s 12 Years A Slave; 2. Joel and Ethan Coen‘s Inside Llewyn Davis; 3. J.C. Chandor‘s All Is Lost; 4. Abdellatif Kechiche‘s Blue Is The Warmest Color, 5. Spike Jonze‘s Her; 6. Alfonso Cuaron‘s Gravity; 7. Jean Marc Vallee‘s Dallas Buyer’s Club; 8. Asghar Farhadi‘s The Past; 9. Richard Linklater‘s Before Midnight; 10. Noah Baumbach‘s Frances Ha; 11. Morgan Neville‘s 20 Feet From Stardom; 12. Ryan Coogler‘s Fruitvale Station; 13. Steven Soderbergh‘s Behind The Candelabra; 14. Paul Greengrass‘s Captain Phillips; 15. Jeff Nichols‘ Mud; 16. Alexander Payne‘s Nebraska; 17. Nicole Holfocener‘s Enough Said; 18. Ziad Doueiri‘s The Attack; 19. Destin Daniel Cretton‘s Short Term 12; 20. Shane Carruth‘s Upstream Color; 21. Gabriela Cowperthwaite‘s Blackfish; 22. John Lee Hancock‘s Saving Mr. Banks; 23. Ron Howard‘s Rush; 24. Henry Alex Rubin‘s Disconnect; 25. Greg ‘Freddy’ Camalier‘s Muscle Shoals; 26. Dror Moreh‘s The Gatekeepers; 27. Penny Lane‘s Our Nixon.

For The Record

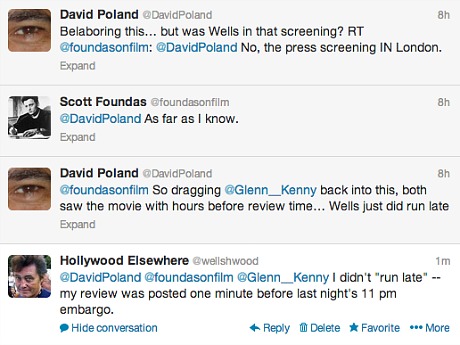

Contrary to tweeted assumptions, I didn’t post my Saving Mr. Banks review “late.” It went up almost exactly concurrent with last night’s 11 pm embargo. Precisely 10:59 pm London time. I don’t care what the time code says. Finis.

Cattle Tortured By Mosquitoes

The British-based Eureka Entertainment already has my order for their upcoming Red River Bluray (streeting on 10.28, arriving in early November) so I can’t do anything about it, but I’m faintly pissed by the screen captures in Dr. Svet Atanasov‘s 10.18 Blu-ray.com review. Every shot appears to be swarming with grainstorm mosquitoes. Which means that the Bluray doesn’t deliver a decent Blu-ray “bump”, or the effect described in my 10.12 review of Sony’s From Here To Eternity Bluray. Atanasov’s words strongly suggest there’s nothing transformative or intoxicating in this new Red River. He’s actually pleased that “there are no traces of problematic degraining corrections” and that “sharpening adjustments have not been performed.” Let’s try this again. I want something better than the last DVD, and if that means a Bluray with “problematic degraining” then please fucking give me that.

Morning Air

My LAX flight leaves Heathrow at 2 pm, or six hours from now. I’ll want to be at the terminal by noon, which means leaving for Heathrow on the Underground by 10:30 am or two and half hours from now. I’m heading out for breakfast now and then I’ll shower and pack. The flight will last 11 hours and 15 minutes…good God. And no wifi. I guess I can do some writing on the pad and then post material when I arrive. Arriving at LAX around five-something. I’ve been up since 4:30 am. Body clock doesn’t know which end is up.

Hang With Us, Give Us The Goods

Yesterday’s viewing of Saving Mr. Banks reminded me once again that the lead performances that win the most applause are (a) almost always from name-brand actors and (b) those that they haven’t stretched or reached for but have relaxed into like an old shoe. We all respect and admire the effort and artistry that goes into an exotic transformational performance, but most of the time we prefer the company of “friends” whom we’ve come to know and feel comfortable with. This is what movie stars do, and why we pay to see them in films and will often praise their “performances”, when in fact they’re mainly just sharing with us in a way that we like. They’re using a little bit of vocal or body English to pass along a feeling of “performing” and that’s fine, but we’re mostly paying for an agreeable hang-out.

In short, movie stars basically play themselves, and that’s all we want them to do. The movie-star performances that win Oscars tend to be those in which the consensus is that “this is the best fit yet — the most natural and filled-out act of self-portraiture this or that actor has ever given us.”

Cigarette Cameo

In yesterday morning’s “What, Me Cancer?” piece, I referenced remarks attributed to Saving Mr. Banks star Tom Hanks during Saturday night’s BAFTA tribute about how Disney execs refused to allow any images of Walt Disney, a three-pack-a-day man until his death from lung cancer in late 1966, smoking in the film. Hanks said there was a “negotiation” about whether or not he could be filmed holding a lit cigarette in a scene, and that the decision was that “he could not.” Actually the film does include a very brief bit in which Hanks/Disney is shown stubbing a butt out in an ashtray. Not holding it or inhaling, God forbid, but at least you can see a flash of a cigarette and a thin plume of smoke before Hanks extinguishes it. So the negotiations yielded something, at least.

Still Love Banks Script

Early last May I ran a rave review of Kelly Marcel‘s script of Saving Mr. Banks. The name of the piece was “If Saving Mr. Banks Is As Good as The Script…” Well, I saw Saving Mr. Banks in London this morning, and I’m sorry to say that the movie I “ran” in my head as I read Marcel’s script seemed a little better than the version I saw today, which has been directed in a cautious, somewhat rote fashion by John Lee Hancock. I didn’t hate or dislike it. I felt reasonably engaged. It pays off reasonably well at the end. But it tries very hard to please, and you can feel that effort every step of the way. And it’s aimed at the squares.

This isn’t to say that Saving Mr. Banks, which will open the AFI Film Fest on 11.7, lacks feeling or spirit or finesse. It has these qualities plus two stand-out performances from Emma Thompson as “Mary Poppins” creator and author P.L. (i.e., Pamela) Travers and Tom Hanks as the legendary Walt Disney. It will be popular, I’m guessing, with those who love the 1964 film version of Mary Poppins as well as the patented Disney approach to family entertainment. And it may snag Oscar noms for Thompson, Hanks and Marcel. And it may make a pile of money from a blend of family and general audiences. But it’s not my idea of a Best Picture contender…sorry. It doesn’t feel carefully measured or focused or shaded enough to warrant that honor. It’s too hammy, too family-filmish — it approaches a farcical tone at times. And it tries too hard to make you choke up.

Soggy Sunday

London Film Festival press-passers (myself included) saw Saving Mr. Banks at 10 am this morning at the Leicester Square Odeon, and then a percentage of same attended the Banks press conference at the Dorchester at 2:45 pm. It also rained a lot. I’m tapping out my review and will post it around 11 pm London time, as requested by Disney publicity. In the meantime here are some diversionary photos and videos — ugly car, beginning of Banks press conference, Dorchester visitors stranded on front steps by rainstorm, hazy head shots, etc.

The ugliest Lamborghini in world history was parked outside the Dorchester this afternoon, obviously owned by someone filthy rich (some Middle-Eastern guy?) and clueless beyond belief. It has to be a guy — no woman would drive around in something like this. I’m also guessing that the style is borrowed from Joseph Kosinski‘s Tron. The guy who bought this car needs to have his wealth impounded and then it needs to be given to the poor.

Cool British Reptile

It’s good that Benedict Cumberbatch has been enjoying his big emergence moment since…what, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy? My personal shorthand is that he’s the new lizard-eyed Richard Burton. Cumberbatch is planted and vivid and very “right now” but he does look like a brilliant fellow with rather cool blood in his veins. That’s not a putdown. It’s just something in his vibe and genes. The feeling of acute intelligence within him is quite fierce. I could be wrong but he’ll never be able to costar in anything dumb or downmarket.