Late this morning I saw Scott Cooper‘s Crazy Heart (Fox Searchlight, early December) and yeah, Kris Tapley was right — Jeff Bridges is definitely in the Best Actor derby for his performance as a grizzled, pot-bellied, booze-swilling, cigarette-sucking ex-country music legend on the downswirl who just manages to save himself from self-destruction. It’s an honestly scuzzy performance — Bridges’ best since The Big Lebowski but tonally opposite and much harder hitting, of course.

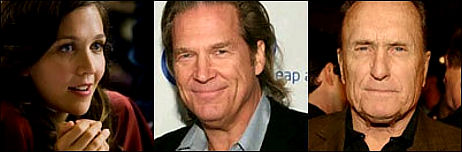

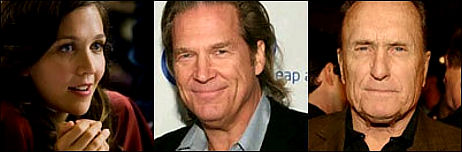

Maggie Gyllenhaal, Jeff Bridges, Robert Duvall

It’s the same kind of “look how gross and dessicated I can be” performance that Orson Welles gave in Touch of Evil — and I say that with genuine respect. Bridges really swan-dives into the toilet, you bet. No sweeteners, no movie-star charm moments, no winking…except when he’s on-stage. The fact that he doesn’t seem to be “acting” in the slightest is what makes it great acting. I believed everything he said and did and went through, especially during the wake-up section (i.e., the final 25 or 30 minutes).

Costar Maggie Gyllenhaal could also nudge her way into the Best Actress contenders club, but then she’s always sharp and on-key and totally “there.”

As noted, the only time Bridges’ Bad Blake is “spirited” is when he’s singin’ and playin’. Otherwise he’s a bulky Uriah Heep during a good 75% or 80% of the film. The title of Bruce Beresford‘s Tender Mercies aptly described the story and the tone of that tough little 1983 film, which is similar in many ways to Crazy Heart (boozy broken-down country singer comes back to life through a love affair with a single mom and her son). I don’t know what Crazy Heart is supposed to refer to but it’s not Bridges’ character, I can tell you that. If they wanted to be descriptive they should have called it Boozy Gut, Smokey Lungs, Old Man Beard-o, Dead Man Sweating and Going Down or…whatever, Mr. Emphysema.

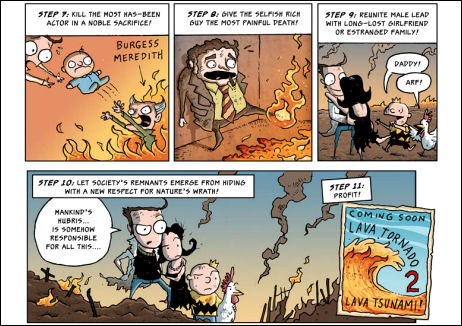

Crazy Heart isn’t a country-and-western version of The Wrestler (Hollywood Reporter columnist Stephen Zeitchik is actually the guy who said this) because it doesn’t end on a note of blunt, fuck-all nihilism. It ends with a settled-down, all’s-well epilogue. Which frankly feels tacked on. This isn’t exactly damaging — it’s fairly harmless — but it doesn’t feel like an organic outgrowth of what came before either.

I had a problem with Gyllenhaal’s Jean Craddock, a single mom in her mid 30s, hooking up in a steady way with Bridges’ Blake. Alcoholics can never be trusted to act like adults — they’re basically children — and there’s no reason for a sober, sensible-minded mother with a four-year-old getting serious with a jowly, grungy, cancer-stick addict who’s at least 25 years older than she and basically a disaster-waiting-to-happen. Sooner or later a guy with booze issues (as well a guy in denial about a son that he abandoned in his youth) will endanger her child, and if she doesn’t realize this she doesn’t have my allegiance. It’s just common sense. The only way I would buy her being with Bridges long-term would be if they were both alcoholics. But she’s not so I don’t. Either way Bridges has bigger tits.

I guess I’m saying that as good as Gyllenhaal always is, I wish her character had been a boozer also, as well as a bit fleshier and older herself. Physically she and Bridges just don’t seem like a match. That’s not her fault or his, of course — that’s just me. Me and Cooper, I mean.

Oh, and Duvall! Duvall is solid oak and genuine as hell as a saloon owner and old-time friend of Blake’s. I was soon wishing he had a larger part and more screen time. There’s never been a false moment from this guy. Never has been, never will be.

That scene Duvall had with Steve McQueen in Bullitt 42 years ago was a omen of things to come. Duvall was a San Francisco cab driver, McQueen was in the back, and the cab was idling on California Street. Duvall: “Two.” McQueen: “Two what?” Duvall: “He made two calls. The second one was long distance.” McQueen: “Howdja know it was long distance?” Duvall (irked): “He put a lot of change in!”