A perverse billionaire seeks me out and say he’s a huge fan of Hollywood Elsewhere, and in return for the good writing and rich observations and recollections over the last 19 years he wants to do me a favor.

He offers me the option of living for free in a two-story, old-world villa in the Trastevere section of Rome — a place he’s owned for decades but never visits. He says I can stay there as long as I want. Which I like the sound of right away — easy travels to various top-tier European film festivals (Cannes, Venice, Berlin) plus I’ve always loved Rome, etc. I thank him and tell him the invitation is highly alluring.

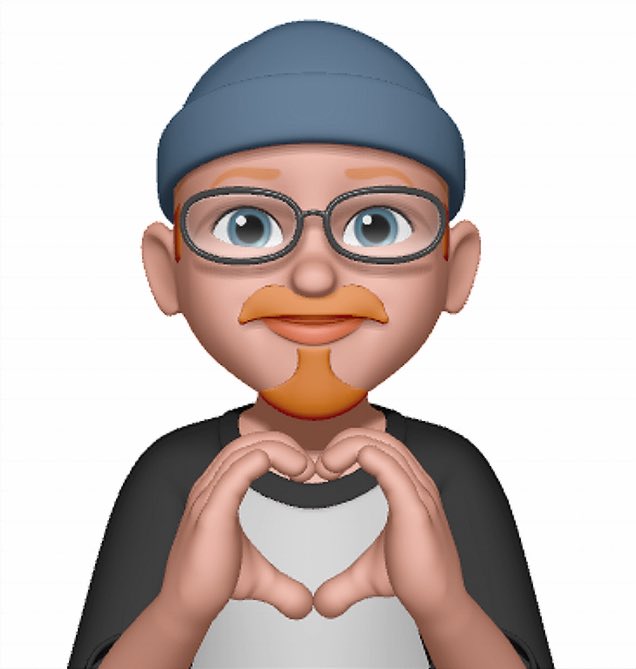

However (here’s the catch) the billionaire insists that a massive blowup of the below emoji must hang on the living room wall, and can’t be taken down. He says it’ll be good for my soul, and will make me a kinder, gentler person. An employee of the billionaire will come to inspect the place randomly, he says, and if the emoji is ever removed I’ll be obliged to move out.

After thinking about living with this emoji I realize that billionaire is not just perverse but the devil himself. I reach out and thank him for his incredible generosity and good heart, but I politely decline the offer.