Repeating: “We’re entering an era where the only films with any chance for success will be the $100 million-plus tentpoles, and reasonably priced films of some perceived quality.”

Developing the riff: “I’ve had far too many fight-the-power wannabe filmmakers cheer this vision of the future, which they believe will usher out the bloated, soul-less big studio retreads and usher in a new democratic era of access to moviemaking fame and glory for all. Lots of people are drinking this Kool-Aid.

“Fifteen years ago, the Sundance Film Festival got 500 submissions. This year, they received 5,000. Virtually all of these are privately financed. There’s only one problem: most of the films are flat-out awful (trust me, I have had to sit through tons of them over the years). Let me put it another way: the digital revolution is here, and boy, does it suck.

“It’s not enough to have access to the moviemaking process. Talent matters more. Quality of emotional content is what matters, period. In a world with too many choices, companies are finally realizing they can’t risk the marketing money on most movies.

“Here’s how bad the odds are: of the 5000 films submitted to Sundance each year — generally with budgets under $10 million — maybe 100 of them got a U.S. theatrical release three years ago. And it used to be that 20 of those would make money. Now maybe five do. That’s one-tenth of one percent.

“Put another way, if you decide to make a movie budgeted under $10 million on your own tomorrow, you have a 99.9% chance of failure.”

wired

George Carlin, R.I.P.

Mel Watkins‘ N.Y. Times obituary for the great George Carlin, who passed earlier this evening at age 71.

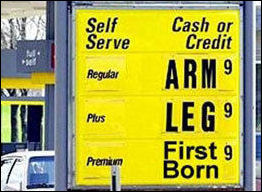

Priceline

I’d like to think that a citizen-artist adjusted the prices on a real-life sign at an actual gas station, rather than some guy Photoshopping it in his basement. I’d also love to find a larger photo of this shot. If anybody has a link…

Misfits Footage

I have a special passion for color photos and color behind-the-scenes photography of famous Hollywood films shot in black-and-white. Which tend to turn up in the special features of DVDs of the films in question. Some Like It Hot, From Here to Eternity, Gunga Din, etc. The owners have given or sold the footage to the DVD producers. Some, like this 8mm color film taken on the set of The Misfits, has turned up on YouTube, although for quality reasons we prefer 16mm color footage at all times.

It just seems odd that someone would pay $60 grand for the original 8mm footage of same. I mean, you just click on YouTube and there it is. If money was an object, why did the owner-seller of the silent 8mm footage keep it off the market for so many years (or decades) instead of trying to sell it 20 or 30 years ago, or peddle it to the producers of the Misfits DVD?

The footage is contained in a 47-minute film, “On the Set with The Misfits,” which was shot by film extra Stanley Floyd Kilarr. Candid-but-posed moments with Marilyn Monroe, Clark Gable, Montgomery Clift, Eli Wallach, Thelma Ritter and director John Huston.

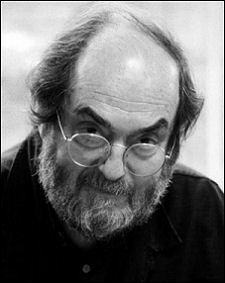

Slammin’ Shut

I remember writing two or three pieces in ’99 and ’00 about how Eyes Wide Shut was a fascinating stiff that essentially portrayed of the decline of Stanley Kubrick. I remember bully-boy David Poland unloading ridicule in my direction because of this. All to say that it gave me comfort to come upon a similar judgment in David Thomson‘s re-review of Kubrick’s final film, which is found on page 273 of Have You Seen…?.

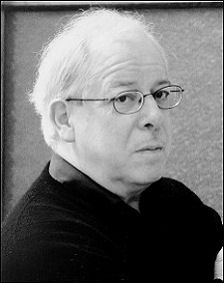

David Thomson, Stanley Kubrick

Here’s the first paragraph and two sentences at the article’s end:

“This is the last film of Stanley Kubrick — indeed, he died so soon after delivery of his cut that the legend quickly grew that he intended doing more things to his movie. But it’s hard at the end not to see the substantial gulf between the man who knew “everything” about filmmaking but not nearly enough about life or love or sex (somehow, over the years those subjects did get left out). Not that the film lacks intrigue or suggestiveness. Mastery can be felt. It is just that the master seems to have forgotten, or given up on figuring out, why mastery should be any more valuable than supremacy at chess or French polishing.”

The last two lines of Thomson’s review: “It is a shock to find that the film is only 159 minutes. Every frame feels like a prison.”

Very succinct. Here’s a March 2000 piece I wrote for Reel.com column that says the same thing with more words. It was called “Stanley Was Slippin’.”

“I [once] referred to Eyes Wide Shut as a ‘perfectly white tablecloth.’ That implies purity of content and purpose, which it clearly has. But Eyes Wide Shut is also a tablecloth that feels stiff and unnatural from too much starch.

“Stanley Kubrick was one of the great cinematic geniuses of the 20th century, but on a personal level he wound up isolating himself, I feel, to the detriment of his art. The beloved, bearded hermit so admired by Tom Cruise and Steven Spielberg (both of whom give great interviews on the Eyes Wide Shut DVD) had become, to a certain extent, an old fogey who didn’t really get the world anymore.

“Not that he wanted or needed to. He created in his films worlds that were poetically whole and self-balancing on their own aesthetic terms. But as time went on, they became more and more porcelain and pristine, and less flesh-and-blood. Eyes Wide Shut is probably the most porcelain of them all.

“The lesson is simple: If you want your art to matter, stay in touch with the world. Keep in the human drama, take walks, go to baseball games, chase women, argue with waiters, ride motorcycles, hang out with children, play poker, visit Paris as often as possible and always keep in touch with the craggy old guy with the bad cough who runs the news stand.

“Kubrick apparently did very little of this. The more invested he became in his secretive, secluded, every-detail-controlled, nothing-left-to-chance lifestyle in England — which he began to construct when he left Hollywood and moved there in the early ’60s — and the less familiar he became with the rude hustle-bustle of life on the outside, the more rigid and formalized and apart-from-life his films became.

“Kubrick’s movies were always impressively detailed and beautifully realized. They’ve always imposed a certain trance-like spell — an altogetherness and aesthetic unity common to the work of any major artist.

“What Kubrick chose to create is not being questioned here. On their own terms, his films are masterful. But choosing to isolate yourself from the unruly push-pull of life can have a calcifying effect upon your art.

“Kubrick was less Olympian and more loosey-goosey when he made his early films in the `50s (Fear and Desire, The Killing, Paths of Glory) and early `60s (Lolita, Dr. Strangelove). I’m not saying his ultra-arty period that began with 2001: A Space Odyssey and continued until his death with A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket and Eyes Wide Shut, resulted in lesser films. The opposite is probably true.

“I’m saying that however beautiful and mesmerizing they were on their own terms, these last six films of Kubrick’s were more and more unto themselves, lacking that reflective, straight-from-the-hurlyburly quality that makes any work of expression seem more vital and alive.

“So many things about Eyes Wide Shut irritate me. Don’t get me started. So many others have riffed on this.

“The stiff, phoney-baloney way everyone talks to one another. The unmistakable feeling that the world it presents is much closer to 1920s Vienna (where the original Arthur Schnitzler novel was set) than modern-day Manhattan. The babysitter calling Cruise and Kidman ‘Mr. Harford’ and ‘Mrs. Harford.’ If there is one teenaged Manhattan babysitter who has ever expressed herself like a finishing school graduate of 1952 and addressed a modern Manhattan couple in their early 30s as ‘Mr.’ and ‘Mrs.,’ I will eat the throw rug in Dave Poland’s apartment. The trite cliches that constitute 85% of Cruise’s dialogue. The agonizingly stilted delivery that Nicole Kidman gives to her lines in the sequence in which she’s smoking pot and arguing with Cruise in their bedroom. That absolutely hateful piano chord that keeps banging away in Act Three.

“The ultimate proof that Kubrick was off his game in his final days? He was so wrong in his judgment that the MPAA wouldn’t hit him with an NC-17 rating for the orgy scene that he didn’t even shoot alternative footage he could use in the event he might be forced to prune the overt nudity. He was instead caught with his pants down and forced to resort to a ridiculous CGI cover-up that makes no sense in the context of the film. (Would Cruise’s sexually curious character be content with just seeing the shoulders and legs of the sexual performers as he walks through the mansion? Wouldn’t he make a point of actually seeing the real action?)

“No one has been blunt enough to say it, but Kubrick obviously played his cards like no one who had any serious understanding of the moral leanings of the culture, let alone a good poker player’s sense of the film business, would have. He played them like an old man whose instincts were failing him, and thereby put himself and Warner Brothers into an embarrassing position. I wish things hadn’t ended this way for him, but they did.

“I hope what I’ve written here isn’t misread. I’ll always be grateful to have lived in a world that included the films of Stanley Kubrick. He’s now in the company of Griffith, Lubitsch, Chaplin, Eisenstein and the rest. Prolific or spare, rich or struggling, lauded or derided as their artistic strivings may have been, they are all equal now.”

Have You Seen?

David Thomson, who is usually my favorite film critic-essayist, has written another huge anthology work (somewhat similar to his The New Biographical Dictionary of Film) running 1024 pages called Have You Seen…?: A Personal Introduction to 1000 Films (Knopf). It won’t hit the stores until 10.24, but uncorrected proofs have been sent out, and I’ve been sinking into my copy with pleasure off and on or the last 48 hours or so.

The book is basically about Thomson going back to each and every film and making them seem curiously fresh and vital again. (And therefore necessary to see once more.) Each re-review and re-assessment runs four or five long paragraphs, and are composed with such smooth and clever assurance that you can knock off 25 or 30 in a single sitting and then return the next day, hungry for more. At no point do you have a feeling that he’s recycled past writings (even if he has here and there).

Here’s a two-paragraph taste of his page 17 take on Aliens:

“Generally speaking, the industrial strategy known as franchising — of doing sequels until the end of time — was a disaster in the 1980s and 1990s. But every now and then, something quite wonderful came of the plodding method. If you put Alien and Aliens side by side (and it may be one of the last great double bills in American film), you get not just the thumping and very satisfactory sequence of prolonged combat after great unnerving threat.

“You also get the emergence of the secret love story in these Alien pictures, the way in which no matter what happens in her movie career, Sigourney Weaver is never going to meet a more faithful lover than the creature. Indeed, its only rivals were the gorillas in the mist.

“Ripley comes back from the first film like Sleeping Beauty in her spacecraft. She looks lovely still, but the journey has taken fifty-seven years. She is brought back to Earth’s drab reality, but she has nightmares. And then she hears that the planet that [Alien‘s] Nostromo went to — it is called LV-426 now — has a small community of miners on it, a few families. And now, as Ripley comes home and wakes after fifty-seven years, the regular signal from LV-426 cuts out. Is there a clearer way the Alien has of calling to Ripley?”

The only thing missing is at least a glancing acknowledgment of the eight-year tragedy of Aliens director Jim Cameron — a guy who was good and imaginative and tough enough to make this film, both Terminator movies, The Abyss and Titanic over a brilliant 13 year stretch (’84 to ’97) and then….nothing.

Cameron is back on it now, somewhat, but for at least eight years he retreated into a kind of rich-man’s sandbox retirement that involved a lot of deep diving, a 3-D documentary, more diving and a lot of kicking back. In short, a complete abdication-renunciation of what he had it in him to do — a Napoleonic retreat from the task of creating smart and exciting movies that matter.

The navel-doodling that guided Cameron from ’98 to ’05 (or ’06) was, for me, shattering. Where would the world be if other men and women of strength and vision in other fields followed Cameron’s example? Think about that.

Ongoing Tragicomedy

Nikki Finke isn’t assessing the catastrophic Nailed shoot with the right spirit. When a film has been shut down for the fourth time because people aren’t getting paid, it might as well be the fifth or the eighth or the twelfth time. This level of repetition pushes events out of the agony realm and into that of near-farce. Meaning that a Lost in La Mancha-styled doc about the making of Nailed could be an inspired tragi-comedy.

This hasn’t been an “indie film shoot from hell,” as Finke has put it, as much as a gift to whomever has had the moxie and foresight to shoot it all (including interviews with ThinkFilm’s Mark Urman and Capitol Films’ David Bergstein) and cut it into something special. The doc that could result might turn out to be better than Nailed itself.

The main-character role that Terry Gilliam played in Lost in La Mancha could be split in the Nailed doc between Urman (the impassioned, frank-talking realist) and director David O. Russell (the gifted filmmaker fueled by anger, aggression and a comic appreciation of the absurd). One thing I would definitely want to see in this doc would be Urman saying the following (which is taken from Anthony Kaufman‘s 6.19.08 Indiewire piece about the ThinkFilm meltdown) straight to the camera, and with feeling.

“I feel terrible if people are hurt by our financial problems. We’re not moving forward on other people’s blood, I can assure you. We’re not [expletive deleted] people — we’re in trouble. And if people end up getting [expletive deleted], we’re [expletive deleted], too, and we can all be on the unemployment lines together.”

Snappy Argument

Conservative wingnut Lars Larson gets bitch-slapped by Newsweek‘s Jonathan Alter (“taking things lower and lower…it’s contemptible”) and The Nation‘s Katrina vanden Heuvel over that cheap Michelle Obama “proud of my country” smear.

MacMurray’s Rescue

Let’s hear it for the opening of the Fred MacMurray Museum in the Heritage Village Mall in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin. It’s opening partly to commemorate the fact that MacMurray, a Beaver Dam resident in his youth, was born 100 years ago. And because he was famous and well-liked for his quick smile, amiable nature and sure touch with comedies. But MacMurray’s rep would be nothing if he hadn’t played a couple of weak, selfish and gone-astray insurance guys in a pair of first-rate Billy Wilder films.

It was MacMurray’s portrayal of Walter Neff, the insurance salesman who couldn’t keep his mind off Phyllis Dietrichson‘s anklets, in Double Indemnity that rescued him from the amiable good-guy thing. He was saved again when he played Jeff Sheldrake, the selfish and manipulative chief of a New York insurance company in The Apartment. Without these two, news of the MacMurray Museum would be limited to local Wisconsin papers and T stations because people like me wouldn’t care that much.

All MacMurray had on his resume otherwise was…okay, Keefer in The Caine Mutiny, but that film belong to Van Johnson and Jose Ferrer. But otherwise his resume was one light and amiable deal after another — My Three Sons, the ’60s TV series, and Bon Voyage, Follow Me, Boys!, The Absent-Minded Professor, The Egg and I, Trail of the Lonesome Pine, etc. Gimme a break.

Nobody’s Perfect

My father, James T. Wells, Jr., had 86 years of good living, mostly. He was miserable at the end, lying in a bed and watching TV, reading and sleeping and not much else. I think he wanted to go because his life had been reduced to this. He was a good and decent man with solid values, and he certainly did right by me and my brother and sister as far as providing and protecting us and doing what he could to help us build our own lives.

But he was also, to me, a crab and a gruff, hidden-away soul (his Guam and Iwo Jima traumas as a Marine during World War II mashed him up him pretty badly) and even, it seemed at times, something of a bitter curmudgeon. But not altogether.

I feel very badly for his suffering the indignities of old age and the mostly horrible life he lived over his final year or two. I know that whatever issues I have with my manner, attitude or personality, it is my charge alone to deal with, modify and correct them. But I also know deep down that Jim Wells was the father of it. He lived in a pit so deep and dark you needed a kleig light to see around.

He was a lifelong Democrat who hated John Wayne for his pro-war posturings. He liked Simon and Garfunkle but never got the Beatles,which always flabbergasted me. He actually thought that Michael Herr‘s Dispatches was a waste of time. My brother tried to get him to watch The Limey and he wouldn’t do it. He lived in his own world and could be a real pain to hang with at times. He was foul and nasty and a snappy contrarian about everything during a trip we took to Lake George about 12 years ago. My son Dylan (who was with us) and I did everything we could to escape his company.

I distinctly remember feeling tear-struck in 1986 when I learned of the death of Cary Grant, whom I’d always regarded as a beloved debonair uncle of sorts. I didn’t feel anything close to that when I heard the news about my dad the night before last. The truth is the truth.

The best thing that happened between the two of us is that by living a kind of cautionary life, he taught me not to be like him. Because he was an aloof, non-affectionate prick with a martini glass in his hand during my childhood, I made a point of being constantly loving and physically affectionate with my kids, and it woke me up to the perils of vodka and lemonade in the mid ’90s. My habit these days is to constantly watch my behavior for the sins of Jim Wells-iness, and when I notice myself acting like him, I correct myself.

In the summer of ’05 I raised a glass of respect to a former next-door neighbor named Doc Sharer at his 80th birthday party at his home in Westfield, New Jersey. I told him it was my ambition to have his joie de vivre and spirited attitude when I got be his age. I don’t ever want to be like my father was, save for his steadiness and creativity and devotion to history books. And yet he did give me the writing bug and the wit and the wiseass attitude.

We went to a 20th Century Fox gathering on the lot a few years ago, and I remember saying aloud upon reading the menu that they would be serving “island food.” Without missing a beat, he looked at me with a solemn expression and said, “Staten Island.” I also introduced him to Tony Curtis during that trip. I remember that he gave Curtis a book of writings by Samuel Johnson.

That was my dad. I’m sorry for my mom and what she must be going through (which I can only guess at) but I’m fine with working and posting today because in personal-emotional terms the man was never a pillar of support or strength for me. The bottom line for me is that he was the guy who did what he could given his baggage and whatnot — he supported me financially and helped me out of three or four jams when I was a struggling New York journalist — but emotionally and spiritually he was a lousy dad and knew it. He told me this in so many words in a rare moment of candor in the mid ’70s. He wasn’t cut out for it.

And one result is that he contributed greatly to psychological and emotional factors that prodded me into being a malcontent — an anti-authoritarian rebel — and which almost turned me into an under-achieving suburban loser. Thank God I had the spirit and the moxie — summoned entirely on my own with no help from anyone — to climb out of that hole.

I trust my father is now at peace. He seemed to find little enough of it while he was alive. He may have known an entire spiritual life that was wonderful and serene for all I know, but the art of the man’s life is that whatever good things were going on inside, he kept most of them hidden.

Saturday Numbers

Get Smart‘s first-choice number was 26 compared to 12 for The Love Guru, so it’s no surprise that Steve Carell, Anne Hathaway, Duane Johnson and Alan Arkin have kicked Mike Myers‘ backside. Smart will end up with $36,627,000 and $9300 a print by Sunday night. The Love Guru opened and closed with a projected $13,976,000 and $4600 a print. Game over.

The Incredible Hulk will make $21,171,000 by Sunday night, which represents a drop from last weekend of about 62%. Not a good hold, especially given that Hulk is not going against another big action film this weekend. It was off 70% last night from previous Friday. On its second Friday Ang Lee‘s Hulk dropped 76.5% with an average weekend fall of 67% or thereabouts, so the new Hulk is doing a little better, but not by much.

Kung Fu Panda will make $20,873,000 — off 36% from last weekend. A decent hold. The Happening will cbe off 67% by Sunday night — a weekend tally of $9,973,000. Indy 4 will make $8070. The total cume is over $290 million, meaning it’s sure to crest $300 million. You Don’t Mess With the Zohan willl make a projected $7,031,000 this weekend, off 57% — it’ll be a push to $100 million.

Sex and the City will hit $6,170,000 — off 37%, $132 million cume. Iron Man has topped $300 million with this weekend’s take of $4,034.000.

Tracking on Disney/Pixar’s WALL*E (opening 5.27) is 84, 41, 10 — a very strong number one week out for an animated feature. Wanted (also 6.27) is tracking at 75, 40 and 5 — fair, not so hot. Will Smith‘s Hancock (7.1) is running at 85,52 and 16 — huge. Guillermo del Toro‘s Hellboy (7.11) is tracking at 69, 33 and 5…okay, decent, not stupendous. Journey to The Center of the Earth (7.11) is running at 59, 17 and 2 — trouble.

Eddie Murphy‘s Meet Dave (also 7.11) is running at 36, 17 and 0 — a bad number no matter how you slice it. I’m guessing that the regular folks started to sour on the guy when the news got out that he bolted out of the Oscar ceremony after he failed to win for Best Supporting Actor. That was the thing that tipped the scales. A Murphy comedy getting a zero first choice three weeks from opening? You tell me what it means, but how many interpretations can there be?