Taking Woodstock director Ang Lee has said he chose the story of struggling motel operator Eliot Tiber (played by Demetri Martin) as a window into the Woodstock Music Festival phenomenon. Except Tiber’s story isn’t very interesting. It seems a little curious and beside the point, and Imelda Staunton‘s bizarre portrayal of Tiber’s paranoid Jewish-gunboat mom almost tips the film into the realm of grand guignol.

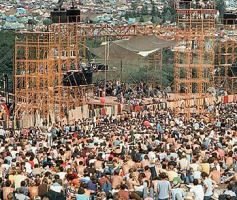

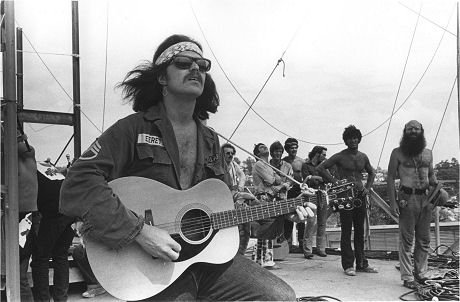

N.Y. Times reporter Bernard Collier; 1969 Woodstock Music Festival & Art Fair

What would have been a lot more dramatic and fascinating in a cultural-echo sort of way is the story of Barnard Collier, the N.Y. Times reporter who pitched his editors on the festival and was turned down, so he attended the festival sans assignment. He then persuaded the editors to run coverage after the crowds and traffic jams became news, and then fought with them tooth-and-nail about the importance of focusing on the event’s scope and cultural significance (along with the well-behaved-kids aspect) instead of emphasizing the rain/mud, sanitation, lack-of-food and drug-use issues.

Part of Collier’s story is recounted in a 8.7 N.Y. Times Arts Beat story by Joshua Brustein story called “Woodstock in Newsprint.”

“Festivalgoers have been known to say Woodstock changed their lives,” Brustein writes. “Some academics and journalism experts have noted that the way the media approached popular culture also shifted significantly with the coverage of the three-day festival.

Collier [has] “described a tension among his editors first about whether it should even cover Woodstock, then about what the story was. His original pitch to write about the festival was rejected. But his brothers, who worked in the music industry, told him that it was worth attending, so he went anyway. After the size of the crowds forced highway closings, he called his editors again, who relented.

“When he started his reporting, Mr. Collier quickly realized that it was not only the Times that had initially ignored the event. He walked into a trailer that the organizers had set up for the press and found it completely vacant. He wrote and contributed to several articles over the next few days, including the one with the explainer on recreational drug use.

“In retrospect it’s fascinating,” said Mr. Collier in an interview earlier this week. “Now everyone knows that stuff. Back then nobody knew.”

I wrote about Collier’s story last April, menioning in particular a paragraph from the festival’s Wikipedia page about the anti-youth-culture attitude of the N.Y. Times editors of the day, and their determination to paint the festival in negative terrms.

“As the only reporter at Woodstock for the first 36 hours or so, Barnard Collier of the New York Times was almost continually pressed by his editors in New York to make the story about the immense traffic jams, the less-than-sanitary conditions, the rampant drug use, the lack of ‘proper policing’, and the presumed dangerousness of so many young people congregating.

“Collier recalls: ‘Every major Times editor up to and including executive editor James Reston insisted that the tenor of the story must be a social catastrophe in the making. It was difficult to persuade them that the relative lack of serious mischief and the fascinating cooperation, caring and politeness among so many people was the significant point.

“‘I had to resort to refusing to write the story unless it reflected to a great extent my on-the-scene conviction that ‘peace’ and ‘love’ was the actual emphasis, not the preconceived opinions of Manhattan-bound editors.

“‘After many acrimonious telephone exchanges, the editors agreed to publish the story as I saw it, and although the nuts-and-bolts matters of gridlock and minor lawbreaking were put close to the lead of the stories, the real flavor of the gathering was permitted to get across. After the first day’s Times story appeared on page 1, the event was widely recognized for the amazing and beautiful accident it was.'”