Kathryn Bigelow and Mark Boal‘s Detroit (Annapurna, 7.28 and 8.4) is a raw-capture history lesson hoping to arouse and enrage, but it mostly bludgeons. I’m saying this with a long face and heavy heart as I like and admire these enterprising filmmakers, but there’s no getting around the fact that they’ve made a brutal, draggy downer. Detroit lacks complexity and catharsis. It doesn’t breathe.

I was hoping that this blistering docudrama, which isn’t so much about the 1967 Detroit riots as the bloody Algiers Motel killings, would play like Gillo Pontecorvo‘s The Battle of Algiers, but alas, nope. Failing that I wanted Detroit to be an investigative political thriller in the vein of Costa Gavras‘s Z, but that wasn’t the scheme either.

No one is more beholden to Bigelow-Boal than myself; ditto their magnificent Zero Dark Thirty and The Hurt Locker. But after these two films I’ve become accustomed to brilliance from these guys, or certainly something sharper, leaner and more sure-footed than this newbie.

At best, Detroit is a hard-charging, suitably enraged revisiting of what any decent person would call an appallingly ugly incident in the midst of a mid ‘60s urban war zone. And of course the system allowed the bad guys to more or less skate or not really get punished. What else is new?

The Algiers Motel incident happened, all right, to the eternal discredit of Detroit law enforcement system back then. But guess what? It doesn’t serve as a basis for an especially gripping or even interesting film.

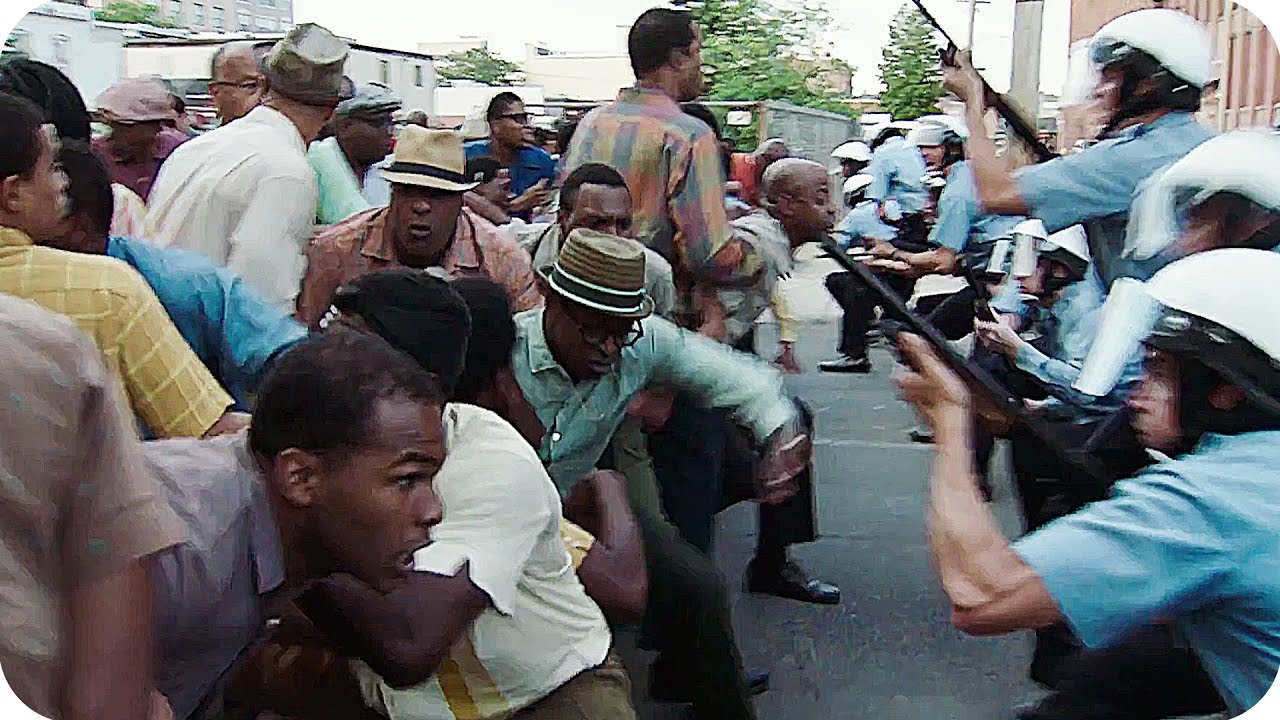

Detroit has good chaotic action, street frenzy, bang bang, punch punch and lots of anger, and I really didn’t like sitting through it and I watched it twice, for Chrissake. For they’ve made a very insistent but air-less indictment film — militant, hammer-ish, screwed-down and a bit suffocating.

In and of itself, the Algiers Motel incident repels but dramatically under-delivers. There’s not a lot of complexity in the portraying, although the episode obviously reflects upon several well-documented 21st Century instances of white-cop brutality and murder.

The white-guilt factor is abundantly earned in terms of the behavior of three pathetically brutal Keystone cops who also happen to be racist fucktards — Will Poulter‘s “Phillip Krauss”, Jack Reynor‘s “Demens” and Ben O’Toole‘s “Flynn”. But it needed more than this.

Ugly, blatant racism in and of itself is obviously repellent, but Detroit doesn’t feel sufficiently layered. It makes for a jarring but rather one-note movie.

The principal actors portraying the victims of harassment — John Boyega as Melvin Dismukes, Algee Smith as Larry Reed, Anthony Mackie as Greene — hold their own; ditto those portraying the shooting victims — Jason Mitchell as Carl Cooper, Nathan Davis, Jr. as Aubrey Pollard and Jacob Latimore as Fred Temple.

I can’t think of a single good sticker line — a line in the vein of Al Pacino‘s greatest Heat moments, say — or anything in the way of clever, diversionary movie craftsmanship. The Detroit script barely feels “written” in the sense that any number of urban thrillers have been. It doesn’t feel tightly sprung or strategized as much as thrown at the wall.

Too often the film feels coarse, pushed, misshapen, misjudged. I plainly, simply didn’t like watching it.

I didn’t even like Barry Aykroyd‘s photography — way too many tight close-ups. And if you ask me the cop haircuts feel a wee bit too long for ’67, when straight-laced society was still rocking short hair and whitewalls. Longish hair (hint of sideburns) didn’t sink into mainstream society until ’69 or ’70 or ’71.

It feels like a decent if rudimentary attempt to recreate the Detroit chaos of ’67 rather than some wowser re-visiting or, you know, a major redefining or rejuvenation of same.

Yes, there are four or five uniformed law enforcement figures plus a nurse (played by Jennifer Ehle) who come off as decent human beings, but otherwise the idea seems to have been to remove any and all shading, dimension and subtlety as far as the white characters are concerned. After a while your spirit wilts in the face of this diseased, cut-and-dried cardboard slime factor.

I’m not saying that white Detroit beat cops were anything but foul and deplorable for the most part back in ’67 (as many cops have recently shown themselves to be when it comes to treatment of black suspects in God knows how many altercations in recent years), but a movie of this sort has to deliver some kind of balance and finesse and shared humanity and quiet-down moments (i.e., we’re all scared children running around on God’s blue planet) or it’s just crude caricature — a racial hit piece.

Whatever the content or mood or metaphorical thrust, all good movies have to feel cinematically sexy. You have to be charmed by their chops, aroused by their strategy. If a movie doesn’t turn you on in one way or another or doesn’t at least make you sit up in your seat, it probably isn’t very good.

I could’ve rolled with Detroit if it had felt more slick and “commercial.” If only it had the look and professional cutting and smooth camerawork and assured pacing of Alan Parker’s Mississippi Burning. Yes, I know — an absurdly inaccurate film history-wise, but a very good one in terms of chops, and a damn sight better than Detroit in this respect. Remember the repetitive hammer music in Parker’s film? Not very melodic but it really worked, really connected.

Detroit makes its points but it’s direct and blunt to a fault. The attack on the bin Laden compound finale in Zero Dark Thirty was 11 or 12 times better than anything in Detroit. Ditto that lively firefight involving Ralph Fiennes’ character in The Hurt Locker.

What happened to the smooth, fleet editing, and the sense of planted authority and versimilitude that I got from Zero Dark Thirty and The Hurt Locker? I’ll tell you what’s happened to it. It’s taken a powder.