In a Sunday N.Y. Times piece called “Hollywood’s Priceless Sounding Board,” Tom Roston collects anecdotes from several Steven Spielberg-influenced directors (JJ Abrams, Matt Reeves, David Koepp, Chris Columbus) about how Spielberg has passed along valuable advice about how to improve their films.

One interesting tale is about Spielberg reading an early draft of Koepp’s Premium Rush, the 2012 bike messenger flick that had a lot of of footage of Joseph Gordon Levitt pedalling fast and hard around Manhattan.

Spielberg’s advice to Koepp was to show JGL “entering the screen consistently from one side when he was going downtown, and to enter the other side when he was going uptown, to help orient the audience,” Roston writes. Make no mistake — that’s an excellent idea. Having an instinctual visual sense has always been Spielberg’s ace in the hole. He’s always respected geography and choreography.

“[Spielberg] is exceedingly practical and grounded in the storytelling,” Koepp remarks. He adds that in passing along this advice Spielberg “referred to how Peter O’Toole‘s character, in Lawrence of Arabia, does the same thing when his character crosses the desert.”

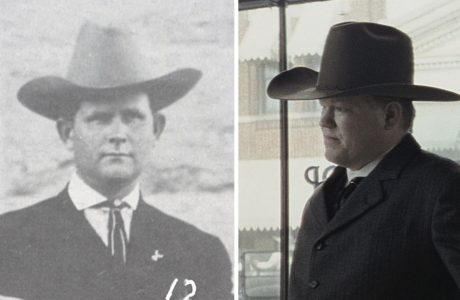

Nope — flat-out wrong. Throughout the film O’Toole’s Lawrence, when trekking across the desert on his own steam, always travels from left to right. On his initial trek with his Bedouin guide (Zia Mohyeddin) to the Maxwell wells and then to Prince Faisal’s camp. During the journey from Faisal’s camp across the Nefud and on to Aqaba. The attack on Aqaba itself. The final campaign against Damascus. All left to right.

The one time O’Toole conspicuously travels in the opposite direction is at the very end, when he’s a passenger in an Army jeep and the British driver goes “Well, sir…goin’ ‘ome!” This may be what Spielberg was alluding to, but this final scene is not about Lawrence “crossing the desert” per se.

One more thing: Koepp, who’s worked as a writer and director on several Spielberg productions, says that “I think, for Steven, sometimes it’s the most fun to weigh in on someone else’s work when there are no consequences. He is free to just talk about the creative part.” This Keopp utterance is what’s known as “obiter dicta” — words in passing that give the game away, and in this instance possibly Spielberg’s.

When Koepp says “consequences” he means (a) consequences of either a structural or story nature, (b) practical-logistical consequences (i.e., how hard or easy will the idea be to film?) or (c) financial or box-office consequences. He’s probably referring to all three, but the very thought of “consequences” always interrupts and for the most part kills the creative process. Allowing “wait…hold on” into your imaginative stream is a perfect recipe for mediocrity. These words are known in the scriptwriting profession as “stoppers.”

I know — I used to consider consequences when I was writing reviews and being careful to shield or camoflauge my true feelings in “film critic-ese” or deciding whether or not to include a dicey or inflammatory quote in an interview piece, and it led only to middling results. I did the same damn thing when I was trying to write scripts in the mid to late ’80s. Only when I stopped being scared of this or that consequence did my writing start to get interesting.

As Spielberg has always been about making audience-pleasing films that earn a lot of money, one can reasonably assume that the “consequence” Koepp was thinking about, the “consequence” that Spielberg didn’t have to keep in mind while brainstorming about somebody else’s film, is ticket sales. Keopp’s quote is vague and therefore not smoking-gun material, but it’s precisely this way of thinking — “Will this scene or bit make the film more likable or entertaining in the eyes of Average Joe audience members and therefore help to increase profitability? — that has defined Spielberg all these decades, and why he’s the kind of filmmaker (with the exception of Schindler ‘s List and to a lesser extent Lincoln) that he is.

Don’t talk to me about Lawrence of Arabia. I know that film up, down, over and sideways. In May 2009 I took this shot of Seville’s Plaza de Espana, the palace-like building where Lawrence (Peter O’Toole) first arrives after being driven into “Cairo” following his trek across the Sinai desert with Farraj (Michel Ray) and Daud (John Dimech).