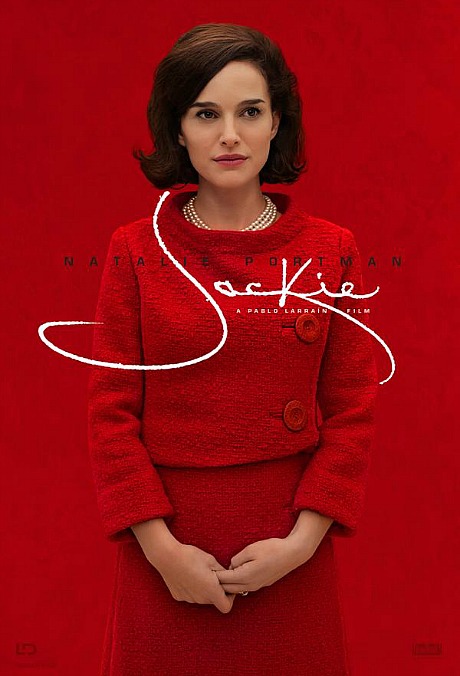

On the occasion of tonight’s big AFI Fest premiere of Pablo Larrain‘s Jackie (Fox Searchlight, 12.2), which I’ve seen twice, I need to lay a couple of things on the line, just to keep the conversation open and frank and upfront.

One, Jackie really is “the only docudrama about the Kennedy’s that can be truly called an art film,” as I wrote after catching it in Toronto. “It feels somewhat removed from the way that gut-slamming national tragedy looked and felt a half-century ago, and yet it’s a closely observed, sharply focused thing. Intimate, half-dreamlike and cerebral, but at the same time a persuasive and fascinating portrait of what Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy (Natalie Portman) went through between the lunch-hour murder of her husband in Dallas on 11.22.63 and his burial at Arlington National Cemetery on 11.25.63.”

And two, after seeing it the second time I went back and re-read a 2.12.10 draft of Noah Oppenheim’s script, which is a whole different bird than Larrain’s film. Pablo cut out a lot of characters and a lot of interplay and a general sense of “this is how it happened” realism, and focused almost entirely on Jackie’s interior saga. And honestly? I discovered that I liked Oppenheim’s version of the tale a little more than Pablo’s.

The script is more of a realistic ensemble piece whereas Larrain’s film is about what it was like to be in Jackie’s head. I fully respect Larrain’s approach, mind, but I felt closer to the realm of Oppenheim’s script. I believed in the dialogue more. The interview scenes between Theodore H. White (played by Billy Crudup in the film) and Jackie felt, yes, more familiar but at the same time more realistic, more filled-in. I just felt closer to it. I knew this realm, these people.

Am I expressing a plebian viewpoint? Yes, I am. I’m saying I slightly prefer apparent realism, familiarity and emotion to Larrain’s arthouse aesthetic.

If anyone who’s seen Jackie wants to read the February 2010 Oppenheim draft, get in touch and I’ll send it along. But you have to see the film first.

Two other reactions to that second viewing, which happened in Santa Barbara a couple of weekends ago: (1) I heard every syllable and vowel that Crudup spoke, but I couldn’t hear 70% of Natalie’s dialogue due to that breathy, whispery delivery and that odd Rhode Island accent (and don’t try to hang this on any hearing issues you think I might be experiencing), and (2) I respectfully disagree with Larrain’s decision not to insert JFK’s funeral procession drums into the soundtrack. Those sounds of somber, muffled grief are just too interwoven with everyone’s memories of that awful weekend. I realize that Larrain’s decision to avoid them was part of his strategy to create his own version of Jackie‘s story, but not sinking into that drum vibe is like making a movie about 9/11 and not showing the planes hitting the twin towers.

From a 4.15.10 post about Oppenheeim’s script, titled “A Lady of Quality“:

“I’ve read enough about those four dark days to understand that Oppenheim’s script is basically a tasteful re-capturing of what happened, and that’s all. It’s an elegant, almost under-written thing — straight, clean, dignified. The dialogue seems genuine — trustable — in that it’s not hard to believe that Jackie or Bobby Kennedy or Larry O’Brien or Theodore H. White or Jack Valenti might have said these very lines in actuality.

“The portrait that emerges isn’t what anyone would call judgmental or intrusive, or even exploratory. Jackie Kennedy is depicted as pretty much the same, reserved, quietly classy woman of legend, determined to honor her husband’s memory by making decisions about aspects of his state funeral in her own way, according to what she feels he would have wanted, or what would be appropriately dignified.

“It’s more or less in the same wheelhouse as Roger Donaldson‘s Thirteen Days, the drama about the Cuban Missile Crisis. I had a feeling that while writing this Oppenheim was mindful of the West Wing stylings of Aaron Sorkin, and how the latter has almost authored a ‘how to’ manual about writing emotionally reserved but affecting stories about people who live and work in the White House. The difference is that this time they’re well-known figures and the dialogue is based on historical accounts.

“Jackie is familiar history re-lived and re-told with a veneer of class.”