This morning I finally got around to reading Kelly Marcel‘s script of Saving Mr. Banks, the story of the contentious script collaboration between Walt Disney (Tom Hanks) and Mary Poppins author P.L. Travers (Emma Thompson) during the development of Disney’s Mary Poppins film, which came out to great success and acclaim in 1964.

Tom Hanks as Walt Disney as Emma Thompson as P.L. Travers in John Lee Hancock and Kelly Marcel’s Saving Mr. Banks (Disney, 12.20).

The script, which appeared on the 2011 Black List, is so wise and clean and well-crafted that you can hear Hanks and Thompson say the lines as you read them. It seems highly likely that Thompson will end up as a lead contender for Best Actress; Hanks will almost surely be nominated for playing Uncle Walt, although there might be a question as to whether his performance belongs in the lead or supporting category.

No one knows how the film will turn out as a whole, but the director, John Lee Hancock (The Blind Side, The Rookie, The Alamo), is probably the most skilled guy in the business when it comes to giving G or PG-rated or family-friendly material a certain echo-y gravitas, so don’t be surprised if Saving Mr. Banks ends up as a Best Picture contender.

It also seems as if a Best Original Screenplay Oscar nomination for Marcel is all but assured. The writing is so skilled, assured and articulate about conflict and the creative process. It’s mostly about Thompson’s Travers (Hanks’ Disney is a co-lead, but his screen time is almost that of a supporting character). The script is split between the present (1961, when Travers went to Los Angeles to collaborate on the Poppins screenplay) and her childhood past in 1907 Australia as she witnessed her banker father, Robert Goff Travers (Colin Farrell), suffer through profesional and financial hell. Her father was the model for Mary Poppins’ brusquely-mannered employer, Mr. Banks.

About 40% to 45% of the film is set in 1907 Australia, and 55% to 60% happens in 1961 Los Angeles and London, but the percentages might be closer than that.

Kelly Marcel

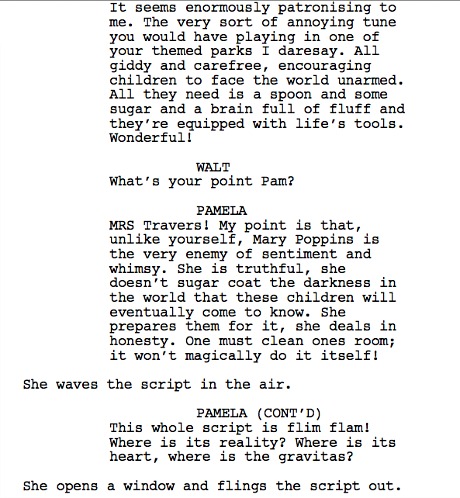

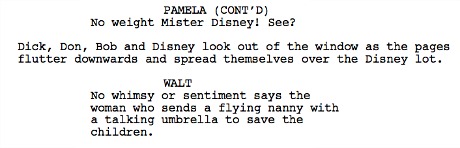

For Travers, Mary Poppins is not about whimsy and fantasy but the difficulties of real adult life and the complex and shadowed fate that awaits all children. For her Poppins is personal — partly a story of her father’s anguish — and is definitely not about sugar-coating, and so while she needs the money, she despises the idea of turning an obviously fanciful and yet lamenting personal tale into a semi-animated Disney “family film.” Marcel’s script conveys an experience familiar to all screenwriters and filmmakers, about the occasional frustration and anguish of translating a work of great personal meaning into a commercial motion picture, and about the dilutions and compromises and (when a family film is being made) sugar-fizz stirrings that are sometimes part of the process.

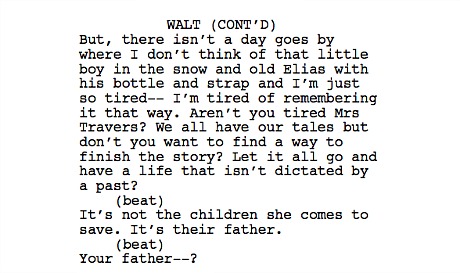

Just read this portion of an argument that happens between Disney and Travers about the tone of the Poppins script:

Some other pics I’ve assembled:

(l. to r.) Julie Andrews, Walt Disney, P.L. Travers at Mary Poppins premiere in 1964.

From the Mary Poppins Wiki page: “According to the 40th Anniversary DVD release of the film in 2004, Walt Disney first attempted to purchase the film rights to Mary Poppins from P. L. Travers as early as 1938 but was rebuffed because Travers did not believe a film version of her books would do justice to her creation. In addition, Disney was known at the time primarily as a producer of cartoons and had yet to produce any major live-action work. For more than 20 years, Disney periodically made efforts to convince Travers to allow him to make a Poppins film.

“He finally succeeded in 1961, although Travers demanded and got script approval rights. Planning the film and composing the songs took about two years. Travers objected to a number of elements that actually made it into the film. Rather than original songs, she wanted the soundtrack to feature known standards of the Edwardian period in which the story is set. She also objected to the animated sequence. Disney overruled her, citing contract stipulations that he had final say on the finished print.

“The film changed the book story line in a number of places. For example, Mary, when approaching the house, controlled the wind rather than the other way around. As another example, the father, rather than the mother, interviewed Mary for the nanny position. Much of the Travers – Disney correspondence is part of the Travers collection of papers in the Mitchell Library of New South Wales, Australia. The relationship between Travers and Disney is detailed in Mary Poppins She Wrote, a biography of Travers, by Valerie Lawson. The biography is the basis for two documentaries on Travers, The Real Mary Poppins and Lisa Matthews’ The Shadow of Mary Poppins.”