“In a way, what Cloverfield does is put a name on the unthinkable,” director Matt Reeves tells L.A. Times guy Mark Olsen in a piece posted yesterday afternoon. He’s alluding to the 9.11 echoes — collapsing skyscrapers, mass evacuations across the Brooklyn Bridge, travelling dustclouds engulfing downtown streets — that makes the film “a repository for the collective unease felt in the wake of a national tragedy,” as Olsen puts it.

It’s intended, in other words, “to explore the very real and obvious fears we are all living with everyday, to let the audience have the experience but in a much more safe and manageable way,” says producer JJ Abrams.

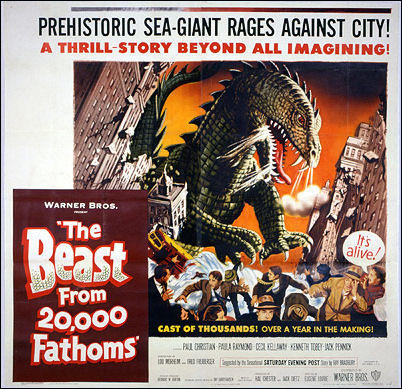

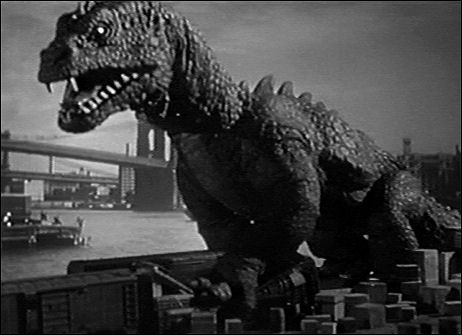

But the subhead of Olsen’s piece — “JJ Abrams aims to provide an old-time rush” — is way off. The basic concept aside, there’s little about this film that stirs specific memories of rampaging monster flicks from the ’50s — those black-and-white B classics like The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms or It Came From Beneath The Sea — or the color-photographed Japanese variants of the late ’50s and ’60s.

As I suggested last week in my inital review, Cloverfield is significantly different from those stop-motion or guy-in-a-monster-suit movies in two ways.

The old monster films were chock-a-block with attempts at rational explanations for the invasion (a beast awakened from a primordial sleep by nuclear testing, etc.) while the characters in Cloverfield don’t know anything and in fact barely get around to asking questions. (There’s one half-assed moment in which the actors try to piece it all together, but the dialogue is in the vein of “whoa, Wikipedia, dude.”)

And the old-time old monster flicks were always about prehistoric-looking beasts or variations thereof — King Kong, Rodan, Mothra, Gorgo, etc. The titanic Cloverfield brute is so divorced from this tradition and in fact is so “nonsensical” that he/she/it stirs associations that are more surreal than anything else. It’s more “whaat?” than “oh my God!,” this thing.

It’s almost a monster film by way of Luis Bunuel. I wrote before that the title could be It Came From Somewhere Deep in the National Psyche, but what we actually see is like a young boy’s nightmare or, as I wrote last week, like a half-nutty, half-horrible dream in the head of a Manhattanite on the morning on 9.12.01.

“I believe there are a whole lot of people who want to have that kind of catharsis and who don’t necessarily want to see documentaries about the very issues they are grappling with internally,” Abrams tells Olsen.