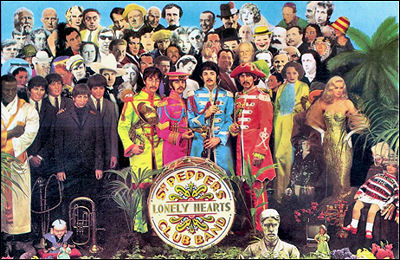

There are several sharp, true-blue observations in Jody Rosen‘s Slate piece about the 40th anniversary of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which was released in England on June 1, 1967 but hit U.S. stores on Wednesday, June 3, 1967. The article is mainly about the album’s musical grooves and innovations, but it also acknowledges the social rumblings and currents of that time, and on this level it’s almost staggering to realize that Rosen totally ignores a seismic impact upon the culture at large that this historic album, almost all by itself, brought about.

Astonishingly and rather suddenly, beginning in June 1967 and continuing long after that, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band seduced a significant portion of America’s middle-class youths into trying the psychedelic drug adventure, which in turn led to a mass injection of satori/God-head consciousness that literally upended liberal American society.

And it was all primarily the doing of LSD — a substance that created such a profound re-ordering and a scrambling of established grooves in one’s thought processes that it allowed for the mystical to slip through and become real — along with the somewhat milder mescaline and peyote. Tens of thousands of American kids wouldn’t have tried these drugs if the Beatles hadn’t conveyed through the easily decipherable symbology of Sgt. Pepper that spiritual seeking and possible transformation through psychedelia was the Great Youth Adventure of the moment — an adventure, a quest and a challenge that only the dumbest or most regressive or most chicken-hearted twentysomethings of that time ignored or hid from.

In short, by triggering a dam burst of pot and psychedelic drug experimentation among under-25 youths, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band led tens of thousands of American kids into the realms of spiritual satori that Herman Hesse and Aldous Huxley had written about. Suddenly a radiant new world of Eastern mystical transcendence and transformation became a tangible thing among the educated free spirits, hippies and pseudo-hippies of that era. This found its ultimate social fruit in the middle-class spiritual movement of the late ’60s and early ’70s that Tom Wolfe later described as “the Third Great Awakening.”

“Very few people went into the hippie life with religious intentions, but many came out of it absolutely righteous,” Wolfe wrote. “The sheer power of the drug LSD is not to be underestimated.”

And there has never been a greater piece of LSD recruitment art in world history than Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. I won’t go into the particulars of how the album’s lyrics and general transformative spirit inspired milions of kids to follow the Beatles on their spiritual path. Rosen’s piece alludes to it here and there; the “drugs” chapter on Wikipedia’s Sgt. Pepper page spells it out pretty clearly.

Before Sgt. Pepper, only rock musicians and various other elites in cities and upscale universities were taking LSD and reading dog-eared paperback copies of the Bhagavad Gita. After Sgt. Pepper, the enlightenment-through-LSD ball game became a mass middle-class thing, thus triggering the above-described spiritual revolution.

The downside is that the mass middle-class element diluted the pseudo-cloistered spiritual purity and coolness of then then-nascent hippie movement. This led to a kind of downmarket mongrelization effect — middle-class dropout runaways looking for spare change in the East Village and Haight-Ashbury, using odious, amphetamine-spiked psychedelic drugs sold by scumbags. This gradually resulted in a degenerative hip-fringe meltdown and that famous September 1967 Haight Ashbury parade proclaiming the “death of Hippie.”

Peter Fonda‘s Terry Valentine character says it concisely in Steven Soderbergh‘s The Limey. The legendary “’60s” boiled down an eighteen-month period, he says — “It was ’66 and half of ’67….that’s all it was.”

Rosen, yes, is mainly writing about the music of Sgt. Pepper, but the fact that she doesn’t even mention what this album engendered in American society, not even anecdotally, is one of the most bizarre examples of what editorial p.c. thinking brings about when the whip has been cracked once too often. Rosen’s piece is like someone writing about J.M. Flagg‘s famous “I Want You”/Uncle Sam recruiting poster of 1917, and not mentioning a little thing that was going on at the time called World War I.

Here’s Rosen’s sum-up paragraph about Sgt. Pepper‘s impact:

“If Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band doesn’t have a concept, it does have a theme. It’s a record about England in the midst of whirling change, a humorous, sympathetic chronicle of an old culture convulsed by the shock of the new — by new music and new mores, by rising hemlines and lengthening hair and crumbling caste systems. In short, it’s a record about the transformations that the Beatles themselves, more than anyone else, were galvanizing.” Rising hemlines!

If there are any under-25s out there haven’t read Wolfe’s “The Me Decade and the Third Great Awakening,” please, please read it now. It’s one of the most brilliant and incisive piece of 20th Century social analysis ever written. And one of the funniest.